Luisa comes to see her primary care provider. Her chief complaint is her acute neck pain which began 2 weeks ago.

Patient Intake

Name

Luisa Sanchez

Gender

Female

Age

69

Height

60 inches

Weight

164 pounds

BMI

32.0

Temperature

98.6 degrees Fahrenheit

Pulse

72, regular

B/P

120/78

Medication Review

- Atorvastatin 40 mg 1/day

- Chlorthalidone 12.5 mg 1/day

- Lisinopril 10 mg 1/day

- Tylenol 1000mg 2/day as needed

Chief Complaint

Neck pain began 2 weeks ago after spending two days making tamales for a church activity; pain is in posterior neck with intermittent headache.

Medical Interpreter

The medical assistant greets Mrs. Sanchez and takes her and her daughter to a room and determines that the primary care provider will need a medical interpreter. The medical assistant calls the University of Iowa Healthcare Interpretation Services Office to have the assistance of a medical interpreter at the appointment.

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act mandates that interpreter services be provided for patients with limited English proficiency who need this service, despite the lack of reimbursement in most states. Medical interpreters facilitate communication between patients and health care providers who speak different languages.

It is important to clarify the difference between an interpreter and translator. An interpreter is utilized for verbal communication and a translator interprets written text. Patients do have the right of refusal of a medical interpreter and may ask to have a family member or another individual provide this service. Children or family members are not recommended as interpreters except when preferred by the patient, unavoidable situations or in the case of emergency.

There are three national certifications for medical interpreters including the Certification Commission for Healthcare Interpreters, National Board of Certification for Medical Interpreters, and The Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf provides certification for deaf interpretation.

Role of Medical Interpreters Challenges and Barriers

Some of the challenges and barriers for medical interpreters include the following:

- Medical terminology can be difficult to translate

- Education level and language variations of the patient must be integrated into the translation

- Untrained medical interpreters are more likely to make errors, violate confidentiality, and increase the risk of poor outcomes.

- Patients may be more comfortable with a family member or friend as an interpreter,

- Untrained interpreters may not share all information to the patient or clinician, and

- The medical interpreter develops a connection with the patient and may be viewed as having a closer relationship than between the patient and clinician.

Role of Medical Interpreters Benefits

The following are some benefits of medical interpreters:

- Provide understanding for the patient AND the clinician

- Cultural liaison between the clinician and patient

- The use of professional interpreters (in person or via telephone):

- Increases patient satisfaction

- Improves adherence and outcomes

- Reduces adverse events

- Improves understanding

- Decreases family or friend burden

- When a bilingual clinician or a professional interpreter is not available:

- Phone interpretation services or trained bilingual staff members are reasonable alternatives.

Role of Medical Interpreters – Considerations

As a clinician you should consider the following when interacting with your patient even when medical interpreter present.

- The clinician should address the patient directly in the first person.

- The clinician should speak directly to the patient.

- Seating the interpreter next to or slightly behind the patient facilitates better communication.

- The clinician should allow for sentence-by-sentence interpretation.

- Allow extra time for the encounter, and

- Limit use of slang, idioms, jargon or humor.

References

- Juckett, G and K Unger. Appropriate Use of Medical Interpreters. American Family Physician. 2014: 9(7): 476-480.

- Jacobs, B et al. Medical Translators in Outpatient Practice. Annals of Family Medicine. 2018: 16(1): 70-76.

Barriers and Challenges for Mrs. Sanchez

Test Your Knowledge: Medical Interpreters

Let’s apply what you’ve learned about medical interpreter to another situation.

You are a nurse working in a rural acute care hospital. You are completing an admission for a patient with a possible diagnosis of pneumonia. You are meeting your patient for the first time and are tying to communicate with her. The patient is having a hard time answering your questions and looks at her daughter to answer the questions. The patient and daughter are communicating in Spanish.

You ask if you can call in a medical interpreter and the patient refuses.

What would you do?

Primary Care Visit: History

Past medical history

- Osteoarthritis

- History of carpal tunnel syndrome

- Hypercholesterolemia

- Hypertension

Smoker

- Yes, quit 2 years ago, smoked 1 pack a day for 30 years

Alcohol Intake

- 3-4 drinks per week

Past Surgical History

- Bilateral carpal tunnel release 1988

Background

- High School Education

Occupation

- A homemaker

Primary Language

- Spanish, speaks little English

Country of Origin

- Came from Mexico at age of 20 (1969) with his husband; became a US citizen in 1973.

Family

- Married for 49 years and lives with husband, 1 daughter and 2 grandchildren ages 2 and 6

Children

- 4 adult children, 12 grandchildren ages 2 to 16

- Family dinners every Sunday after church

Location

- Small rural town in Iowa with high percentage of Hispanic population; primary care provider is 16 miles from her home.

Psychosocial

Hobbies

- Bowling – in a league 1-2 times a week; plays cards

Social Activities

- Helps care for grandchildren; takes grandchildren to and from school each day; also picks up 2 other grandchildren from school each day.

Religion

- Catholic church – completes home visits and cooking for special events. Goes to church 2x week (Wednesday and Sunday).

Primary Care Provider – Pain Assessment Tools

In this case scenario, the primary care provider utilizes evidence-based practice tools to assess pain and psychosocial concerns. The faces pain scale, revised, in Spanish is used to assess pain. Based on the faces pain scale, Luisa rates her current pain as 6/10 with best at 2 of 10, and worst at 8 of 10.

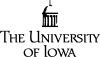

PCP – Public Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ-2)

Depression Screen

To address psychosocial concerns, Luisa completes two questionnaires to assess depression and anxiety. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) is a depression screen tool. There are two items in this tool which Mrs. Sanchez is asked to rate each item for the last two weeks. The items are:

- Little interest or pleasure in doing things and

- Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless.

This tool has a 4-point scale with scores of zero for “not at all”, 1 for “several days”, 2 for “more than half of the days”, and 3 for “nearly every day”.

The cut off score for concerns about depression from the total of both items is a score of 3 for both items.

Luisa’s score is 1 and 1 for both items, so total score is 2.

Reference

Haggman et al. Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders Procedure (PRIME-MD). Physical Therapy, 2004

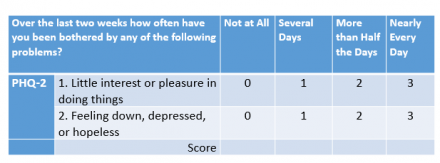

PCP – Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-2)

The second tool used to assess psychosocial concern is The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 2.

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-2) is an anxiety screening tool. Similar to the PHQ2, there are two items in this tool which Mrs. Sanchez is asked to rate how she has been bothered by each item in the last two weeks. The items are:

- Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge?

- Not being able to stop or control worrying

This tool has a 4-point scale, zero for “not at all”, 1 for “several days”, 2 for “more than half of the days”, and 3 for “nearly every day”.

The cut off score for concerns about anxiety from the total of both items is a score of 3 for both items.

Luisa’s score is 0 and 0 for both items, so total score is 0.

Reference

Kroenke K et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity and detection. Ann. Inter. Med 2007: 146: 317-325.

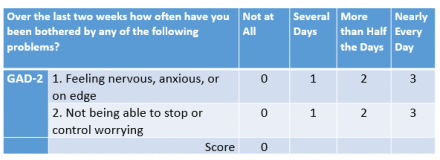

PEG

The PEG is a brief, multi-dimensional pain measure for use with older adults. This tool looks at three areas:

- (P) for average pain intensity

- (E) for interference with enjoyment of life

- (G) for interference with general activity

Luisa’s scores 6 for pain intensity, 6 for enjoyment of life, and 8 for general activity respectively. Her total score is 20; when you divide by three for a mean score out of 10, she scores a 6.3 out of 10, indicating a moderate impact of pain for pain, enjoyment and activity.

Community of Faith

A community of faith is important in the Hispanic community.

83% of Hispanics/Latinos in the United States have a religious affiliation, and about 55% of Hispanics/Latinos are Roman Catholic. A community of faith can provide a support role for health and mood. This support system may act as a coping mechanism to diminish depression and anxiety.

Spirituality and religiosity are intertwined with cultural values in Hispanic families. Faith is interwoven with their daily lives and serve as a foundation for emotional support and spirituality. In a survey of 1,005 Hispanic regarding religion, suffering and self-rated health resulted in the following:

- Older Hispanics who attend church more often are more likely to search for something positive in the face of suffering,

- Older Hispanics who have a perceived close personal relationship with God are more optimistic, and

- Older people who are more optimistic are more likely to rate their health in a favorable way.

Faith, family, and community work together for Hispanics in the United States. A community of faith is a foundation and source of empowerment for the challenges of moving to a new country. Changes in geography, culture, and language provide challenges for many U.S. Hispanics.

Health Related Behaviors

A community of faith may play an important role in health and health related behaviors. A medical encounter is a situation where it would be helpful to know the support system of the person in pain.

Biopsychosocial Model

A community of faith is an important component of a biopsychosocial model. The community of faith may assist in psychosocial support and influence the experience and management of pain.

Impact on Health

A community of faith is a cornerstone of the Hispanic culture and can also influence the experience and management of pain for the patient, provider and family.

References

- Campesino M and Schwartz GE. Spirituality Among Latinas/os Implications of Culture in Conceptualization and Measurement. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2006; 29 (1): 69-81.

- Funk C. and Martinez J. 2014. Fewer hispanics are Catholic, so how can more Catholics be hispanic? Pew Research Center. 2014. Available from: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/05/07/fewerhispanics-are-cath….

- Lerman S, Jung M, Arredondo EM, Barnhart JM, Cai J, Castañeda SF, et al. (2018) Religiosity prevalence and its association with depression and anxiety symptoms among hispanic/Latino adults. PLoS ONE 13(2):e0185661.

Primary Care Provider – Interview

Acute Neck Pain

- Acute neck pain onset is often unexplained and can result from:

- Trauma or injury

- Inflammation

- Poor muscular control

- Deconditioning

- A person with neck pain may experience a wide range of possible symptoms.

- Pain, especially in the back of the neck, that worsens with movement

- Pain that peaks after the injury, instead of immediately

- Muscle spasm or guarding in the neck and upper back and pain in the upper shoulder

- Headache in the back of the head

- Increased irritability, fatigue, difficulty sleeping, and difficulty concentrating

- Numbness in the arm or hand

- Neck stiffness or decreased range of motion (side to side, up and down, circular)

- Tingling or weakness in the arms

Pain Related Experience of Hispanic Americans

Pain Conditions

- Hispanic respondents report fewer pain conditions compared to non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic Black respondents

Co-Morbidities

- Depression and anxiety are highly comorbid with pain and can lead to more functional impairment and worse patient outcomes

Sleep Deficit

- Problems falling and staying asleep are common complaints among patients experiencing pain

Community of Faith

- In traditional Hispanic cultures, pain and illness are viewed as disharmony with or punishment from God. The theme emerged during interviews with Mexican Americans living with chronic pain – pain was discussed as a loss of spiritual connectedness or as conflict with God, while God was also viewed as the provider of help from pain

Work Related Exposure

- Hispanic Americans disproportionately work in blue-collar and manual labor occupations with greater safety risks that expose them to pain. Consistent with this exposure, Hispanic Americans report more occupational pain and injury than non-Hispanic whites.

Reference

Hollingshead et al. The pain experience of Hispanic Americans: A critical literature review and conceptual model. J Pain 2016 May; 17(5): 513-528.

Acute Neck Pain Management

Acute neck pain:

- Most episodes of acute pain resolve within 8 weeks

- Some patients continue with ongoing symptoms or a recurrence of neck pain for more than a year

- Non-pharmacological strategies are an important component of treatment

- Pharmacological strategies are used in conjunction with non-pharmacological strategies

- It is important to monitor the patient for red flags

Red flags are signs and symptoms that indicate something more serious in nature may be occurring and include:

- History of cancer or vascular disease

- Neurological findings

- Changes in bowel or bladder

- Fever, nausea or vomiting, unexplained weight loss, torticollis

References

- Bier JD, Scholten-Peeters WGM, Staal JB, et al. Clinical practice guideline for physical therapy assessment and treatment in patients with nonspecific neck pain. Phys Ther. 2018;98:162–171.

- Blanpied PR et al. Neck Pain: Revision 2017. Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health From the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017;47(7):A1-A83. doi:10.2519/jospt.2017.030

- Cohen, SP and WM Hooten. Advances in the diagnosis and management of neck pain. BMJ 2017;358:j3221

Acute Neck Pain and Risk Factors for Chronic Neck Pain

Risk factors for chronic neck pain for Hispanics include:

- Higher body mass index

- Depression

- Smoking

- Heavy alcohol use

- Poorer self-rated health

Risk factors for chronic neck pain with acute neck pain

- Female

- Higher baseline pain intensity

- Multiple pain sites

- Smoking

- Obesity

- Poor general health

- Variety of psychosocial factors

References

- Bui J et al. Immigration, Acculturation and Chronic Back and Neck Problems Among Latino-American. Immigrant Minority Health (2011) 13: 194-201.

- Cohen, SP and WM Hooten. Advances in the diagnosis and management of neck pain. BMJ 2017;358:j3221

Review of Systems and Physical Exam- Results

- Musculoskeletal

- Neck pain present for the last 2 weeks, intermittent headache

- Arms: No difficulty; denies numbness or tingling

- Legs mobile, no significant report of weakness, no falls

- Feet, no complaints

- Focused review of symptoms: otherwise unremarkable

- Alert, oriented.

- Endocrine: No temperature changes or weight gain.

- Lungs:

- Denies shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, cardiopulmonary or changes in exercise tolerance.

- No constipation or diarrhea, no bowel variations

- Good appetite, no changes in weight.

- Denies incontinence of bowel or urine.

Observation and Posture

Patient with no areas of redness. Appearance of swelling in upper trapezius region. Patient with elevated shoulders, Increased forward head, increased thoracic kyphosis, flattening of lumbar spine, protruding abdomen.

Range of Motion

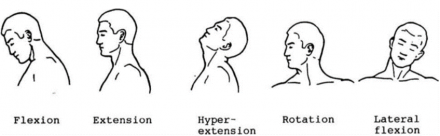

- Neck: Limited active range of motion (AROM) limited with cervical flexion, bilateral rotation and side bending

- Upper Extremities: Within functional limits in Active Range of Motion

- Lower Extremities: No deficits noted in Active Range of Motion

Strength

WNL for BUE, BLE and grip.

Palpation

Jaw exam

No pain with palpating the TMJ bilateral, jaw with click on left to open close and glide. Slight enamel wearing on front teeth. No palpable trigger points along masseter. However, pain present with palpation over the SCM insertion into mastoid process.

Lymph

No palpable, nodes, neck supple.

Gastrointestinal

Abdomen soft, nontender, no hepatosplenomegaly, and bowel sounds present.

Neurological Exam

- Conversant appropriately.

- Light touch sensation normal, upper extremity

- Reflexes normal.

- Gait and Balance: No deficits noted in balance or in gait.

Response to Physical Exam

- Increased pain with exam activities and maneuvers

Primary Care Provider Initial Visit – Plan of Care

Non-Pharmacological Strategies

There are many non-pharmacological strategies for acute neck pain. The most common non-pharmacological strategies for pain management include physical therapy, topical pain relievers, psychosocial support and complementary approaches.

Physical therapy non-pharmacological strategies may include manual therapy, exercise, posture, patient education and Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS). Topical applications can range from the use of heat or cold to topical mentholated or coolant gels or creams. Psychosocial support may involve cognitive behavioral therapy, a Community of Faith, prayer, and emotional support. Additional nonpharmacological strategies include Massage Therapy, activity modifications, exercise, relaxation, distraction, breathing exercises, music or meditation.

References

- 1Bier JD, Scholten-Peeters WGM, Staal JB, et al. Clinical practice guideline for physical therapy assessment and treatment in patients with nonspecific neck pain. Phys Ther. 2018 98:162–171.

- 2Blanpied PR et al. Neck Pain: Revision 2017. Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health From the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017;47(7):A1-A83. doi:10.2519/jospt.2017.030

- 3Lakhan, S et al. The effectiveness of aromatherapy in reducing pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Research and Treatment 2016; 2016:8158693.

Pain Primary Care Provider Order Set

This order set includes first line, second line and third line recommendations for pain management.

Order Set 1

First Line (Step One Treatments)

Non-Pharmacological Orders: Weight control, Exercise, Physical Therapy, Occupational Therapy, TENS, Heat, Cold, Over the Counter Topical with Menthol.

Pharmacological Orders

NSAIDS, Topicals, Acetaminophen

Referrals

Outpatient Physical or Occupational Therapy, Psychiatry, Pain Psychology, Social Work, or Other

Other

Reference

Sluka, KA and Rakel, BA Primary Investigators, Development of an Electronic Prescription Bundle of Non-Pharmacological Strategies for Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. Pfizer and American Pain Society Grant , 2017. Grant ID Number: 28431973, University of Iowa.

Order Set 2

Second Line: (Step Two Treatments)

Second line treatments are additive to first line treatments.

Non-Pharmacological Orders

Non-pharmacological treatment and consults should be considered, continue and ordered in this stage.

Pharmacological Orders

Pharmacological treatments from first line treatments may need to be continued. Possible additions of Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCA), Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI), or Muscle Relaxants

Labs

Thyroid, Electrolytes, Sedimentation Rate, CRP, ANA, Other

Imaging

X-rays

Reference

Sluka, KA and Rakel, BA Primary Investigators, Development of an Electronic Prescription Bundle of Non-Pharmacological Strategies for Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. Pfizer and American Pain Society Grant , 2017. Grant ID Number: 28431973, University of Iowa.

Order Set 3

Third Line (Step Three Treatments)

Third Line treatments are additive to first- and second-line treatments.

Non-Pharmacological Orders

Non-pharmacological treatment and consults should be considered, continue and ordered in this stage.

Pharmacological Orders

Orders from first- and second-line treatments may need to be continued. If not further surgical or interventional approach, consider opioid usage.

Imaging

MRI

Testing

MG, NCV

Referrals

Pain Clinic, Orthopedics, Neurosurgery, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Rheumatology, and other.

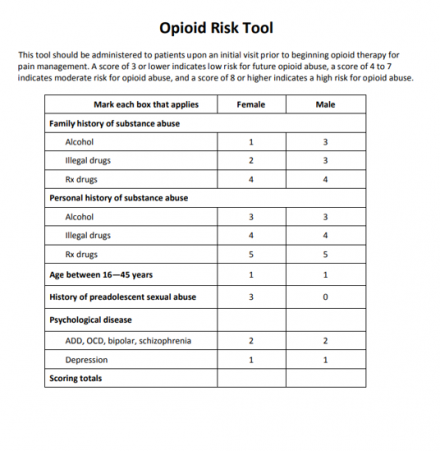

Opioid Usage

Oral, topical or intrathecal infusion. Providers may consider prescribing opioids if steps one and two, pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches have not been successful and the following have been initiated: opioid risk tool (ORT) and an opioid contract signed.

Reference

Sluka, KA and Rakel, BA Primary Investigators, Development of an Electronic Prescription Bundle of Non-Pharmacological Strategies for Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. Pfizer and American Pain Society Grant , 2017. Grant ID Number: 28431973, University of Iowa.

Opioid Risk Tool Revised

Prior to prescription of an opioid, an opioid risk for addiction assessment is indicated. The most common assessment is the opioid risk tool.

The Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) is a self-report screening tool designed for use with adult patients in primary care settings to assess risk for opioid abuse among individuals prescribed opioids for treatment of chronic pain.

This tool was not indicated in the care of Luisa.

References

- Martin D. Cheatle PhD , Peggy A. Compton RN, PhD , Lara Dhingra PhD ,Thomas E. Wasser PhD, MEd, CIM , Charles P. O’Brien MD, PhD , Development of the Revised Opioid Risk Tool to Predict Opioid Use Disorder in Patients with Chronic Non-Malignant Pain, Journal of Pain (2019),doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2019.01.011

- Webster LR and R Webster. Predicting aberrant behaviors in Opioid-treated patients: preliminary validation of the Opioid risk tool. Pain Med. 2005; 6 (6):432.

Patient Centered Goals Ranked

Mrs. Sanchez has ranked her goals from 1 to 9

- Decreased pain

- Improved mobility

- Cooking for family

- Caretaking with grandkids

- Community of faith

- Driving as needed

- Helping her husband

- Sleeping without pain

- Weekly bowling

Special Tests

No further testing indicated at this time.

Interactive Plan of Care

What do you think are the top four best non-pharmacological strategies for Mrs. Sanchez?

Interactive Acute Pain Risk Factors

What risk factors for chronic pain does Mr. Sanchez have? Select all that apply:

Primary Care Provider – End of Session Instructions

The primary care provider has completed her examination of Luisa and will share her assessment, education about acute pain and instructions for Luisa.