Introduction

Mary is a 74-year-old woman who is coming in to see her primary care doctor reporting new right-sided hip pain. Mary has a history of metastatic breast cancer that has been stable on hormone therapy for several years. She also has metastasis to her ribs. Her other medical problems include diabetes mellitus, hypertension and generalized osteoarthritis. The medications she is currently taking include anastrozole for breast cancer, amlodipine for hypertension, glyburide for diabetes and, acetaminophen for pain.

Mary lives alone in a senior community. She is very active in the bridge club and regularly attends the history lectures and movie nights. She has a daughter who lives an hour away and a son who lives out of state. She travels less now than she used to but enjoys seeing her grandchildren when they come to visit.

Taking the Health History

Meet Mary

- 74 year old woman with right-sided hip pain

- Past medical history:

- history of breast cancer metastatic to ribs

- hypertension

- type 2 diabetes mellitus

- osteoarthritis

- Medications

- anastrozole

- amlodipine

- glyburide

- acetaminophen

Pain Assessment

Mary presents with a new pain during a visit to her primary care physician.

What other questions do you have for Mary?

Pain Assessment

One commonly used, standardized and comprehensive approach to pain assessment is the pneumonic PQRST. This device prompts you to ask about provoking and alleviating factors, the quality of the pain, the region and radiation of the pain, its severity, and timing.

PQRST

- P - Provoking/relieving factors

- Q - Quality

- R - Region/radiation

- S - Severity

- T - Timing

P - Provoking/relieving factors

- “What brings the pain on or makes it worse?”

- “What have you tried for the pain?”

- Ask about:

- Medications: prescription and over the counter

- Nonpharmacological treatments

- Ice, heat, massage and distraction

- Relation to activity

- Body position

- Movements

Q - Quality

- “How would you describe this pain?”

- If they need words, can offer

- “Is it stabbing, burning, throbbing, aching or something else?”

Based upon Mary’s description of her pain, what do you think is the most likely cause?

Pain Description and Clues to Origin

The information about the quality of pain gives us important insight into its possible origin and pathophysiology that in turn informs the choice of initial treatment.

For example, somatic pain—such as the pain experienced when you strain a muscle or break a bone—tends to be well localized and sharp or aching.

Visceral pain, on the other hand, is typically experienced as deeper and more difficult to localize. A patient will often move his or her hand over a region rather than pointing to an exact spot that hurts.

Neuropathic pain is also poorly localized but is described differently. Typical words used to describe neuropathic pain include burning, tingling, or shooting. Descriptions are often creative and visual. For example, a patient may invoke the image of bees or ants in their socks, or a blow torch burning their skin.

Continue reviewing the next slides about pain location and severity at your own pace.

| Types of Pain | Physiological Component | Pain Characteristics | Example of Cancer Pain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nociceptive Pain - Somatic | Either cutaneous (skin) or deep (bone, muscle, blood vessels) |

|

Bone pain |

| Nociceptive Pain - Visceral | Internal organs and body cavity lining |

Poorly localized Diffuse, aching, squeezing |

Hepatic capsule pain, Bowel obstruction |

| Nociceptive Muscle Spasm | Stimulation of nerve endings | Pain upon fast contraction | Muscle cramping |

| Neuropathic Pain - Peripheral | Peripheral nerve injury |

|

Neuroma |

| Neuropathic Pain - Central | Injury to central nerves |

|

Spinal cord compression |

| Neuropathic Pain - Mixed | Both peripheral and central |

|

Chemotherapy induced neuropathy |

R - Region/radiation

- Where is the pain?”

- “Has the pain moved since it started?”

- “Does it seem to radiate or go anywhere

S - Severity

- “Can you rate your pain now on a 0 to 10 scale, where 0 is no pain, and 10 is the worst pain you can imagine?”

- Use the words the patients uses

- Ask about pain now, at its best, at its worst

- Note that this is subjective

- An 8 for one person might be a 2 for another

Terminology and Pain Rating Scales

Use common terminology and an understandable scale.

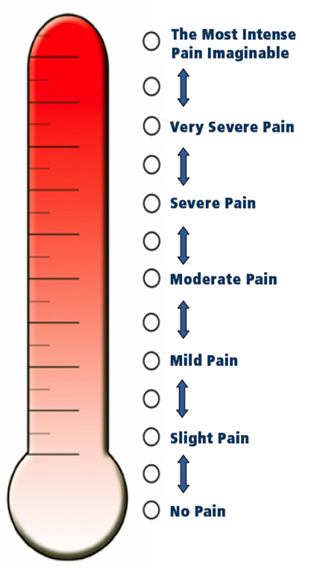

There are multiple ways to measure pain intensity. The most commonly used is the zero to 10 numeric rating scale. Some patients have a difficult time attaching a number to their pain so verbal descriptors or visual depictions such as the Iowa pain thermometer, shown here, facilitate obtaining this information. It is important to evaluate pain with the same scale in a particular patient over time so that changes in pain in response to treatment can be accurately monitored.

Verbal Descriptor Scale

- Pain as bad as it can be

- Severe pain

- Moderate pain

- Mild pain

- No pain

Iowa Pain Thermometer

Reference

Herr K, Spratt KF, Garand L, Li L. Evaluation of the Iowa pain thermometer and other selected pain intensity scales in younger and older adult cohorts using controlled clinical pain: a preliminary study. Pain Medicine. 2007 Oct 1;8(7):585-600.

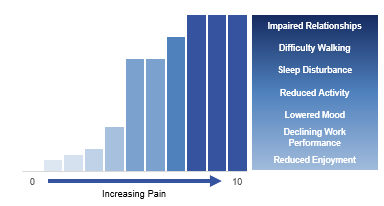

Pain Intensity and Functional Interference

As pain intensity increases, so does the degree of functional interference.

In addition to measuring pain intensity, the clinician should measure the degree to which pain interferes with the patient’s function. The level of functional interference from pain increases as the severity of pain increases. Low levels of pain may impact one’s capacity to enjoy life, while higher levels of pain may impact even basic activities, such as walking and sleeping as well as mood and relationships with others. As a way to personalize care, the clinician should monitor the degree of pain-related activity interference over time, and not focus simply on measuring pain intensity.

T - Timing

- “How long have you had this pain?”

- If the patient had pain prior to the cancer: “Is it similar to that pain, or different?”

- “Are there patterns throughout the day?”

More Information on Mary's Pain

Mary’s pain is in her right upper outer thigh. She describes it as dull and deep and it does not radiate. It is brought on by standing for a prolonged period. She rates her pain as six out of ten at its best and nine out of 10 at its worst. It is constant and, so far, nothing is helping to relieve it. It is worse at night and interferes with her sleep.

Mary also has a history of osteoarthritis but she states the current pain does not feel similar to her prior flares of osteoarthritis pain.

P - Provoking Factors

Standing for a long time

R - Relieving Factors

None

Q - Quality

Dull, deep in nature.

R - Region/Radiation

The pain is located on the lateral upper femur, with no radiation.

S - Severity/Timing

The pain at best is 6/10, at worst 9/10. It is constant, including at night, and affects her sleep.

Note: Mary has a history of arthritis, but the pain is not similar to her previous arthritis pain.

How might cancer contribute to Mary's pain?