Post-Test Questions

Question 1

Which one of the following medications is NOT approved by the FDA for the management of fibromyalgia?

Question 2

Chronic pain patients who tend to catastrophize about their pain:

Question 3

Which one of the following medications that works as a weak opioid agonist and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor has evidence to support its use in fibromyalgia?

Question 4

Which one of the following statements about medications for fibromyalgia is TRUE?

Question 5

What is the most common diagnosis for Temporomandibular Disorders?

Question 6

Which of the following is NOT an example of a non-pharmacologic therapy for treating TMD and/or fibromyalgia?

Question 7

Which of the following TMD structures, upon palpation, can refer to the ear? (more than one can be correct).

Question 8

What causes TMD?

Question 9

Increased responsiveness of nociceptive neurons to their normal input, and/or recruitment of a response to normally subthreshold inputs can be defined as:

Question 10

Co-existing systemic disorders seen in fibromyalgia include all of the following EXCEPT:

Self-Care Therapies

We use our mouths for so many activities (talking, eating, yawning, laughing) and when we are not engaged in these, we need to allow our jaw muscles and joints to relax. Many people have developed habits that do not permit their muscles or joints to relax a sufficient amount of time. The following will help instruct you on how to relax your jaw muscles and joints to reduce the jaw pain you are having:

1. Apply moist heat, ice or a combination of heat and ice to the painful areas, most people prefer heat but if that increases your pain, use the combination or just the ice.

a. Use moist heat for 20 minutes two or four times each day. Moist heat can be obtained by

wetting a towel with very warm water. It can be kept warm by wrapping it around a hot water bottle or placing a piece of plastic wrap and heating pad over it. It also can be rewarmed in a microwave oven or under the very warm water.

b. Use the combination of heat and ice two to four times each day. Apply the heat as

recommended above for 10 minutes then lightly brush the painful area with an ice cube wrapped in a thin washcloth. Repeat this sequence four or five times.

c. Apply ice wrapped in a thin washcloth to the painful area until you first feel some numbness

then remove it (usually takes about 10 minutes).

2. Eat soft foods like casseroles, canned fruit, soups, eggs and yogurt. Don't chew gum or eat hard (raw carrots) or chewy foods (caramels, steak, bagels). Cut other food into small pieces, evenly divide the food on both sides of your mouth and chew on both sides.

3. Rest your jaw muscles by keeping your teeth apart and practicing good posture.

a. Your teeth should never touch except lightly when you swallow. Closely monitor yourself for

the habit of clenching that you may have developed. People will often do this when they are driving the car or concentrating. Try keeping your jaw relaxed by placing your tongue lightly behind your upper front teeth, having your jaw in a comfortable position with your teeth apart and relaxing your jaw muscles.

b. Good head, neck and back posture help you to have good jaw posture. Try to hold your head up straight and use a small pillow or rolled towel to support your lower back. Avoid habits as resting your jaw on your hand or cradling the telephone against your shoulder.

4. Avoid caffeine, because it stimulates your muscles to contract and hold more tension in them. Caffeine or caffeine-like drugs are in coffee, tea, most sodas, and chocolate. Decaffeinated coffee also has some caffeine, while Sanka has none.

5. Avoid habits that strain your jaw muscles and joints, such as clenching, grinding or resting your teeth together; biting your cheeks, lips, or objects you put in your mouth; pushing your tongue against your teeth or holding your jaw in an uncomfortable or tense position.

6. Avoid sleeping habits that strain your jaw muscles or joints, by not sleeping on your stomach and if you sleep on you side, keeping you neck and jaw aligned.

7. Restrain from opening your mouth wide, such as yawning, yelling or prolonged dental procedures.

8. Use anti-inflammatory and pain reducing medications such as ibuprofen (Motrin), naproxen (Aleve), ketoprofen (Orudis KT), Tylenol, aspirin and Percogesic to reduce joint and muscle pain. Avoid those with caffeine, i.e. Anacin, Excedrin or Vanquish. There is no “cure” for TMD and you may need to follow these instructions for the rest of your life. Your dentist may suggest other therapies in addition to these instructions. No single therapy has been shown to

be totally effective for TMD and a percentage of patients receiving TMD therapies report no symptom improvement, i.e., 10-20% of patients receiving occlusal splints report no improvement. Based on your symptoms and identified contributing factors, an individualized treatment approach will be recommended and it may be revised as your symptom response is observed.

Stretching Your Jaw Muscles

People unconsciously stretch many of their muscles throughout the day. Patients who have jaw muscle stiffness or pain often find a significant improvement in their symptoms with this jaw stretching exercise. Your dentist believes your symptoms will improve if you perform this simple jaw stretching exercise 6 times a day, between 30 and 60 seconds each time, at the opening and duration you determine best for you.

It is best to warm your jaw muscles before you stretch by slowly opening and closing about 10 times. You may also warm your muscles by applying moist heat to them (allow time for the heat to penetrate into your muscles). While stretching you need to concentrate on relaxing your lips, facial muscles and jaw. Do not bite on your fingers while stretching, they are only to give you a guide for the width you are stretching.

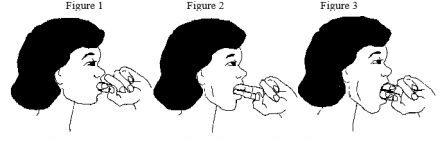

You will need to determine what opening and duration are best for you. To determine this, the first time you stretch, bend your index finger and place the middle knuckle between your upper and lower front teeth (see Figure 1). Hold this position for 30 seconds. Do this exercise 6 times per day for 30 seconds each time. If this does not aggravate your symptoms, the second time you stretch, increase the time to 45 seconds. If this does not aggravate your symptoms, the exercise should be done for 60 seconds. If this does not aggravate your symptoms, increase your opening width to 2 fingertips (see Figure 2) and cut your time back to 30 seconds.

Continue increasing your time and opening in this manner (starting with 30 secs and increasing to 60 seconds for each increase in opening) but do not go beyond 3 fingertips. Find the largest opening and duration that does not cause even the slightest discomfort or aggravation of your symptoms and use this each time you stretch. If you experience any discomfort or aggravation which lasts more than 5-10 minutes, decrease your opening or time.

As your symptoms improve or if you have a flare-up, you will need to increase or decrease this opening and time. Be very careful not to cause yourself any aggravation with this exercise, because this may hurt your progress.

Patients may report this exercise will not provide immediate symptom improvement and initially may increase symptoms for the first week. After 1-2 weeks benefits should be noticed. Similarly, stopping does not cause immediate loss of these benefits, but also tends to take 1-2 weeks to be noticed. With the normal symptom fluctuation most TMD patients experience, it is often difficult for them to relate their symptom improvement or aggravation with the starting or stopping of this exercise.

As your symptoms improve or if you have a flare-up, you will need to increase or decrease this opening and time. Be very careful not to cause yourself any aggravation with this exercise, because this may hurt your progress.

Etiology of Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD)

What is TMD?

A collection of musculoskeletal disorders of the head and neck region involving the muscles of mastication and jaw joints. Included in this definition should be headaches, neck, and ear pain that are influenced by jaw function.

Epidemiologic studies have shown that 40-70 % of the population exhibit signs and symptoms of TMD. 30 - 45 % of the population have jaw joint sounds. Approximately 7% of these persons will have symptoms severe enough to require treatment.

Why do some of these with signs and symptoms of TM Disorders have dysfunction while others do not? We’re not sure.

Almost all of the studies looking at the etiology of TMD are point of time studies that are measuring prevalence (they show how common a sign, symptom or characteristic associated with TMD is). They can show an association of TMD with certain subject characteristics, such as type of occlusion, personality, or history of trauma, but cannot prove that these factors lead to or cause TMD. There are few studies that are prospective in nature (following subjects with certain characteristics over a period of time to see which factors lead to TMD) so as to determine the incidence of TMD in persons who have certain characteristics.

When a patient presents with facial pain one has to make a diagnosis. One must determine if their Chief Complaint is a TMD. Or do they show signs of migraine, intra-cranial lesion, neoplasm, radiculopathy, tooth pulpalgia, 3rd molar pericornitis (inflammation/infection), etc that require referral to a different medical or dental specialty?

Once you’ve determined that the patient is in the right place (has a TMD), is their CC primarily a TMJ (joint) or muscle problem, or both? Assuming you’ve made the diagnosis, now how are you going to treat this patient?

This is where treatment planning gets difficult. If we don’t know what is causing the patient’s problem, how are we going to effectively treat it?

We do have success in managing the majority (80%) of persons suffering from TMD, by using non-invasive, conservative treatment regimens involving self-care, dental appliances, physical therapy, and behavioral therapy regimens. But there still are a significant number of patients (5-20%) that are refractive to treatment and require more physically- and time-invasive therapy. How to best manage these refractive patients is where the controversy starts. Is surgery, occlusal rehabilitation, or mental health therapy what these patients need?

There exists many “ TMD camps” that propose one or another treatment for their patients with TMD, sometimes with the exclusion of any other treatment. And all of these treatments have had success. Why? Because TMD is a collection of musculoskeletal disorders with different causes and which fluctuate in symptom intensity. If one initiates a treatment as a patient’s symptoms are subsiding the treatment is credited with the success. One might then infer that whatever the intervention was designed to treat is the cause of TMD. Was it TMJ surgery to reduce a displaced disc? Was it a tooth equilibration to correct a malocclusion? Was it an occlusal splint that increased the vertical relation of a patients bite? Was it a regimen of Elavil to help the patient sleep better? All of these interventions have been proposed to be the correct treatment for persons suffering from TMD. Some providers exclusively propose just their specific treatment for all patients who present with symptoms of TMD, leading to many patients being over treated and /or being subjected to unnecessary expensive and invasive treatments.

How you manage your patient who presents with TMD should depend on what you feel is the etiology of their problem. Hopefully you will individualize how you treat the patient based on the specific findings of their history and clinical exam.

Here are some of the etiologic factors that could “cause” TMD:

They could be predisposing, initiating, or perpetuating (contributing) factors.

- Trauma

- Macro (MVA)

- Micro (bruxism, tooth clenching)

- Occlusion

- Orthodontics

- Gender

- Joint Laxity

- Disc position

- Lateral pterygoid hyperactivity

- Psychosocial factors (stress, anxiety, depression, personality)

- Co-morbidities (rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes)

If one wants to get a better understanding of what we know of the etiologic basis of TMD, one has to look at the pain research from the last 10 years.

Chronic pain has been defined as pain of 6 months or more in duration. We now know that people can develop the signs and symptoms of chronic pain much quicker than that. Signs of chronic pain, such as hyperalgesia, allodynia, and spontaneous pain can occur as quickly as 3 months after a prolonged injury. For instance, examine the symptoms from a sunburn; there is spontaneous pain (it hurts without being stimulated), it has allodynia (it hurts to wear a shirt over the sunburn, ie a lower pain threshold to a non painful stimulus), and when the sunburned area is stimulated there is hyperalgesia (prolonged pain to a painful stimulus). Should this response to the sunburn continue, one can develop peripheral and central nervous system changes that can enhance and prolong the pain experience. Research in neuroscience has shown that pain should no longer be thought of as symptom of disease, but is an aggressive disease by itself.

To understand why let’s consider the trigeminal nerve. Prolonged peripheral stimulation of teeth, TMJ’s, or muscles of mastication can lead to peripheral nerve secretion of neuropeptides that provide a feedback loop to further inflammation and pain perception. In acute injury this forces one to decrease use and stimulation of the area so that it can heal. Should the injured body part have to be used, CNS inhibition (pain modulation) can occur to prevent pain perception. Should the stimulation continue central nervous system changes can occur that allow pain perception even though there is no longer a physical explanation for the pain. Animal studies have shown that continued stimulation of wide dynamic range (WDR) and n methly d adenosine (NMDA) neurons at the 2nd order neuron level in the brain stem can lead to an expansion of the receptive fields so that a small peripheral stimulus will be perceived as a large stimulus in the brain cortex, hence PAIN. This expansion of receptive fields in the subnucleous caudalis can lead to referred pain as 2nd order neurons from cranial nerves IIV, IX, X, and cervical nerves 1-3 lie in the vicinity of the trigeminal nerve. We know that deep pain can refer to cutaneous areas but that cutaneous pain does not refer to deep tissues. This is due to the difference in types of neurons that innervate the skin compared to those that serve deep structures. Muscle nociceptors seem to have a greater tendency to exhibit receptor field expansion than nociceptors which innervate joints. This could explain why muscle symptoms can continue long after a patient has adapted to an anatomical TM joint derangement such as a disc displacement. We know that endogenous opioids that act on inhibitory Gaba neurons at the 2nd neuron level to reduce the CNS perception of peripheral nerve stimulation. If a person is suffering from untreated depression, they could have limited pain modulation ability contributing to their increased perception of pain and leading to CNS sensitization.

Recent studies have used conditioned pain modulation tests (CPM) during which repeated mechanical stimulation of one area is done while the patient is experiencing a noxious (painful) stimulus to another area to measure the effectiveness of the patient’s pain modulation ability. An example would be having the patient put their hand in a cold bath while having their masseter muscle palpated. CPM tests measure the function of the descending pain inhibitory pathways involving the endogenous opioid system. Findings from these studies have indicated that TMD patients can have the same response to these tests as do patients with other chronic pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia (FM) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS); indicating a common problem with how these patients modulate pain perception.

TMD subjects who respond to a treatment such as appliance (splint) therapy might be benefiting from a placebo effect from wear of the appliance; i.e. the inhibitory effect of the endogenous opioids released due to the placebo effect from appliance therapy is responsible for the positive response to occlusal appliance treatment.

Now, let’s tie this all together in a concept for the etiology of TMD. Most people adapt to a non-ideal disc position or to a muscle strain to eventually have minimal symptoms and normal function. But, should they be predisposed to prolonged injury because of a systemic disease such as rheumatoid arthritis, or an unstable occlusion, or depression, or they have a habit such as bruxism that perpetuates the injury they might not be able adapt or heal. Prolonged nociception could lead to peripheral and/or central nervous system sensitization with their perception of pain continuing long after the physical findings initiating their pain have disappeared.

When devising a treatment plan for a TMD or any pain patient, one must be deductive in understanding why that patient is not able to adapt, heal and function normally. One has to understand and manage the predisposing, initiating, and perpetuating factors influencing the patient’s pain presentation to have treatment success.

Case 2 Pain Management Center

Selected literature

TMJ Disorder

This article is listed as an important update in the Dynamed entry on TMJ Disorder.

Intraoral myofascial therapy associated with improved pain and opening range in adults with chronic myogenous temporomandibular disorder (J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2012 Jan) J Manipulative Physiol Ther

Countway does not have this journal. I recommend that you request it through the BWH Medical Library interlibrary loan service. This service is free and it will be faster than the service at Countway where we have half of the people who work in that department are now gone. You can contact them at Phone: 617-732-5684 or http://www.bwhpikenotes.org/employee_resources/Medical_Library/default…

Diagnosis

American Society of Temporomandibular Joint Surgeons. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of disorders involving the temporomandibular joint and related musculoskeletal structures. Cranio. 2003 Jan;21(1):68-76

Not available at Countway. Request through BWH Library as above.

American Society of Temporomandibular Joint Surgeons. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of disorders involving the temporomandibular joint and related musculoskeletal structures. Cranio. 2003 Jan;21(1):68-76

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) plus biofeedback associated with reduced pain and depression at > 3 months in patients with temporomandibular dysfunction Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011 Nov 9;(11):CD008456

There are citations for 24 systematic reviews of TMJD therapies at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/myncbi/collections/public/1VcplcUYUEfB-odOzt9vkGw/

As one introduction pointed out there is no clarity as to the most effective treatment.

CAM study: A pilot whole systems clinical trial of traditional chinese medicine and naturopathic medicine for the treatment of temporomandibular disorders.(includes abstract) Ritenbaugh C; Hammerschlag R; Calabrese C; Mist S; Aickin M; Sutherland E; Leben J; Debar L; Elder C; Dworkin SF; Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine, 2008 Jun; 14 (5): 475-87. (journal article - clinical trial, research) ISSN: 1075-5535 PMID: 18564953

(Many other CAM studies including Cochrane reviews –largely inconclusive -- but this was the largest so best evidence)

Case 2 Fibromyalgia: Diagnosis Evaluation Management

Diagnosis

From Dynamed:

American College of Rheumatology 2010 diagnostic criteria:

- criteria intended to supplement rather than replace ACR 1990 criteria

- intended to be simpler to use in clinical practice

- diagnosis of fibromyalgia if all of

- widespread pain index (WPI) ≥ 7 and symptom severity (SS) scale score ≥ 5 or WPI 3-6 and SS scale score ≥ 9

- symptoms present at similar level for ≥ 3 months

- absence of disorder that would otherwise explain pain

- Reference - Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010 May;62(5):600 PDF

- This message contains search results from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) at the U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM). Do not reply directly to this message

1. Guidelines on the management of fibromyalgia syndrome - a systematic review:

Häuser W, Thieme K, Turk DC.

Eur J Pain. 2010 Jan;14(1):5-10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.01.006. Epub 2009 Mar 4. Review. PMID: 19264521 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

2. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity.

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Katz RS, Mease P, Russell AS, Russell IJ, Winfield JB, Yunus MB.

3. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010 May;62(5):600-10. doi: 10.1002/acr.20140. PMID: 20461783 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

Exercise for fibromyalgia: a systematic review.

Busch AJ, Schachter CL, Overend TJ, Peloso PM, Barber KA.

J Rheumatol. 2008 Jun;35(6):1130-44. Epub 2008 May 1. Review.

PMID: 18464301 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

4. The role of antidepressants in the management of fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Häuser W, Wolfe F, Tölle T, Uçeyler N, Sommer C.

CNS Drugs. 2012 Apr 1;26(4):297-307. doi: 10.2165/11598970-000000000-00000. Review.

PMID: 22452526 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

5. Efficacy of hypnosis/guided imagery in fibromyalgia syndrome--a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials.

Bernardy K, Füber N, Klose P, Häuser W.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011 Jun 15;12:133. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-133. Review.

PMID: 21676255 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE] Free PMC Article

6. Gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults.

Moore RA, Wiffen PJ, Derry S, McQuay HJ.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Mar 16;(3):CD007938. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007938.pub2. Review.

PMID: 21412914 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

7. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of amitriptyline, duloxetine and milnacipran in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review with meta-analysis.

Häuser W, Petzke F, Üçeyler N, Sommer C.

Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011 Mar;50(3):532-43. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq354. Epub 2010 Nov 14. Review.

PMID: 21078630 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE] Free Article

8. Psychological treatments for fibromyalgia: a meta-analysis.

Glombiewski JA, Sawyer AT, Gutermann J, Koenig K, Rief W, Hofmann SG.

Pain. 2010 Nov;151(2):280-95. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.011. Epub 2010 Aug 19.

PMID: 20727679 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

9. Traditional Chinese Medicine for treatment of fibromyalgia: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials.

Cao H, Liu J, Lewith GT.

J Altern Complement Med. 2010 Apr;16(4):397-409. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0599. Review.

PMID: 20423209 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE] Free PMC Article

10. Efficacy of acupuncture in fibromyalgia syndrome--a systematic review with a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials.

Langhorst J, Klose P, Musial F, Irnich D, Häuser W.

Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010 Apr;49(4):778-88. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep439. Epub 2010 Jan 25. Review.

PMID: 20100789 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE] Free Article

11. Efficacy of hydrotherapy in fibromyalgia syndrome--a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials.

Langhorst J, Musial F, Klose P, Häuser W.

Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009 Sep;48(9):1155-9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep182. Epub 2009 Jul 16. Review.

PMID: 19608724 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE] Free Article

12. Treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome with antidepressants: a meta-analysis.

Häuser W, Bernardy K, Uçeyler N, Sommer C.

JAMA. 2009 Jan 14;301(2):198-209. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.944.

PMID: 19141768 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

Overview of Clinical Examination for a TM Disorder

The following is an overview of the clinical examination (ROM, palpation, auscultation (assess joint sounds)) for a TM disorder and the diagnostic criteria and treatment recommendations for specific joint and muscle problems.

Clinical Examination

The TMJs range of motion (ROM) in opening and in lateral movements along with noises should be noted. Joint sounds which occur repetatively are significant. Observe the pattern of opening; the mandible will deflect towards the joint that is not translating. Ask the patient to point to the areas that are painful during function. The masticatory muscles and the TMJs should be palpated for tenderness. Often TMJ tenderness can not be evaluated until the patient opens slightly, bringing the TMJs from under the zygomatic arch. The TMJ’s are then palpated on the lateral poles. The retrodiscal tissue is then palpated by having the patient open wide and pressing posterior to the condyle or placing your little fingers in the patient’s ear and pulling forward. The cervical muscles and spine may be palpated for tenderness; sometimes masticatory pain is primarily due to referred pain from the cervical area. When determining if the palpation sensitvity is related to the patient’s chief complaint (CC) ask three questions when palpating; Is this pain or pressure?, Is the pain familiar?, does the pain go anywhere?

Intraoral and extraoral swelling or deflection of the soft palate should be appraised. If pulpal (tooth nerve) pathosis is suspected, the tooth should be tested for a hyper-responsiveness to cold, heat and palpation. If these tests are positive, consider an anesthetic injection of the tooth to determine the impact the tooth is having on the patient’s pain complaint. If clenching or bruxism is suspected, significant wear facets, ridging on the lateral borders of the tongue, and/or intraoral hyperkeratosis on the cheeks should be observed. Have the patient clench their teeth and also stretch their jaw open for 60 seconds each or until pain/discomfort occurs to determine if such jaw function is associated with their CC.

Panoramic imaging is a standard of care during a TMD exmination to rule out dental or jaw pathology. Additonal imagining is warranted when the clinical exam implicates a primary joint problem, the patient‘s bite is changing, or there is a suspicion that the disorder may be linked to prior trauma. Additional imaging is also indicated when the patient does not respond to therapy as anticipated and imaging findings have the potential to change the patient’s course of therapy, or if the patient is being evaluated for TMJ surgery.

Diagnostic Categories

Identifying the primary and secondary diagnoses are often difficult because TMD disorders tend to have similar symptoms and often occur concurrently. The following categories are the diagnostic classifications established by the American Academy of Orofacial Pain (AAOP). The diagnostic criteria are not meant to be rigid, but rather provide clinical guidance for diagnosis; your clinical judgment should be relied on for final diagnostic decisions.

Diagnostic Criteria for Masticatory Muscle Disorders

1. Myofascial pain: a) regional dull aching pain, generally aggravated by masticatory muscle function, b) hyper-irritable sites (trigger points) which can increase and refer the pain, c) moderately limited active ROM which can be increased with passive opening.

2. Myositis: a) pain in a localized muscle following injury or infection, b) diffuse tenderness over the entire muscle, c) increased pain with muscle use and d) moderate to severe limited ROM due to pain and swelling.

3. Myospasm: a) acute pain at rest as well as with function and b) continuous muscle contraction causing a marked decrease in ROM (if involves lateral pterygoid muscle will usually cause malocclusion).

4. Local myalgia: this category is for multiple muscle pain disorders for which we have not yet determined diagnostic criteria, i.e., muscle pain from protective splinting, fatigue, autonomic effects, etc.

5. Myofibrotic contracture: a) limited ROM, b) unyielding firmness on passive stretch, c) little or no pain unless involved muscle is forcibly stretched and d) there may be a history of trauma, infection, surgery, radiation or long period of not stretching muscle to its full length.

Treatment involves the use of analgesics and muscle relaxants to initially decrease pain so as to encourage compliance with a home rehabilitation program, and to manage acute relapses. There is no scientific support for the use of these medications long term for muscle pain. Associated headaches need to be adequately managed with abortive and preventative medications as needed. A stabilization dental appliance (occlusal orthosis) should be used to reduce influence of occlusal factors and bruxism when they are present. Behavior modification should include stress management, relaxation training, coping skill development, and the implementation of habit control regimens to decrease aggravating habits such as nail-biting and daytime clenching. The keys to long term successful management is the elimination of contributing factors such as parafunction, poor sleep, anxiety, depression, occlusal instability, headaches, posture problems.

Physical therapy intervention should initially involve the use of modalities to decrease pain and gentle stretching exercises to keep the joint mobilized, muscles working, and gradually increase jaw opening. The physical therapist or clinician should help the patient develop a home rehabilitation program with stretch and spray, postural-re-education, ergonomic awareness, aerobic exercise, and gentle mobilization. The goal of therapy is a gradual increase of pain free range of motion with home rehabilitation and control of contributing factors. Generally, range of motion increases with muscle problems can be aggressively increased when compared to the increase of range of motion with a primary joint problem. One must go much slower when rehabilitating a joint problem; increasing range of motion within the patient’s pain tolerance.

Diagnostic Criteria for Joint Disorders

1. Congenital absence - faulty or incomplete development of mandible or cranial bone

2. Developmental disorders (rarely cause TMD)

b. Hypoplasia - underdevelopment of mandible or cranial bone

c. Hyperplasia – over development of mandible or cranial bone

d. Neoplasia - abnormal tissue growth

3. Disc displacement:

a. Disc displacement with reduction: 1) reproducible joint noise that occurs at variable positions during opening and closing and 2) soft tissue imaging reveals disc displacement that reduces during opening and hard tissue imaging does not reveal extensive osteoarthritic changes, 3)Deviation on opening to the affected side initially but returns to midline upon full opening

b. Disc displacement without reduction, acute: 1) persistent marked limited opening (<35 mm) with history of sudden onset, 2) deflection to the affected side upon opening, 3) marked limitation to the contralateral side and 4) soft tissue imaging reveals disc displacement without reduction and hard tissue imaging does not reveal extensive osteoarthritic changes

c. Disc displacement without reduction, chronic: 1) history of sudden onset of limited opening that occurred more than 4 months ago and 2) soft tissue imaging reveals disc displacement without reduction and hard tissue imaging does not reveal extensive osteoarthritic changes.

3. Dislocation (also known as open-lock): a) is the positioning of the condyle anterior to the articular eminence which cannot be reduced by the patient. b) inability to close the mandible without specific manipulative maneuver and c) radiographic evidence reveals condyle well beyond the eminence.

4. Inflammatory disorders:

a. Synovitis and capsulitis: 1) TMJ pain increased by palpating the TMJ, loading the TMJ (putting upward and backward pressure on the mandible), and during function, and 2) hard tissue imaging does not reveal extensive osteoarthritic changes.

b. Polyarthritides (joint inflammation and structural changes caused by a generalized systemic polyarthritic condition): 1) pain with function, 2) point TMJ palpation tenderness, 3) limited ROM secondary to pain and 4) hard tissue imaging reveals extensive osteoarthritic changes.

5. Osteoarthritis:

a. Primary osteoarthritis (deterioration of subchondral bone due to overloading the regenerative capacity of the joint): 1) no identifiable etiologic factor, 2) pain with function, 3) point TMJ palpation tenderness and 4) hard tissue imaging reveals structural bony changes (subchondral sclerosis, osteophyte, or erosion).

b. Secondary osteoarthritis (deterioration of subchondral bone due to trauma, infection or polyarthritides): 1) identifiable disease or associated event, 2) pain with function, 3) point TMJ palpation tenderness and 4) hard tissue imaging reveals structural bony changes (subchondral sclerosis, osteophyte, or erosion).

6. Ankylosis:

a. Fibrous ankylosis: 1) limited ROM, 2) marked deviation to affected side, c) marked limited laterotrusion to the contralateral side, d) radiographic findings that reveal absence of ipsilateral condylar translation on opening.

b. Bony ankylosis: a) Extreme limited ROM when condition is bilateral, b) marked deviation to affected side, c) marked limited laterotrusion to the contralateral side, d) radiographic evidence of bone proliferation and absence of condylar translation.

Treatment for Joint Disorders

Management for intracapsular disorders should start with patient education as to the nature of their problem. These are musculoskeletal injuries which a have a strong potential to become chronic because of ever-present jaw function requirements and contributing factors such as parafunction, anxiety and depression. It is very important to have the patient understand their role in limiting function to allow healing (such as a pain–free diet) and in doing the therapeutic exercises to rehabilitate the joint. They need to be taught how to use medications such as NSAIDS and muscle relaxers to control their symptoms. A short-term steroid regimen such as Medrol Dose Pack (dexamethosone) can be used to initially decrease the symptoms of capsulitis by reducing inflammation.

Physical therapy can be used to reduce inflammation and increase pain free ROM with ice, ultrasound, and phonophoresis. Gentle range of motion exercises should be done by the patient within pain tolerance (the TMJ should not hurt for more than 3-5 minutes after the exercise period). Exercises should be done frequently for short periods (6 times a day for 30-60 seconds).

The physical therapist can do gentle distraction and mobilization of the TMJ to increase pain free ROM. Iontophoresis can be considered especially if the patient has a good response to a medrol-dose pack.

An orthotic (nightguard) can be very effective in reducing forces on the joint to promote healing. It can control parafunctional behavior at night, temporarily stabilize an uneven occlusion, and allow the joint to rest.

Lastly, a surgical procedure such as arthrocentesis or arthroscopic lysis and lavage can be considered based on the patient’s response to reversible treatment. Surgical treatment should only be considered if the patient’s complaints are localized to the TM joint.

Jeffry R Shaefer DDS, MS, MPH

Recommended References

1. A new way for TMJ. Harvard Health Letter. February 2009 Pages 4-5 www.health.harvard.edu

2. List T, Axelsson S. Management of TMD: evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Oral Rehabil. 2010 May;37(6):430-51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2010.02089.x. Epub 2010 Apr 20. Review. PMID: 20438615 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE

3. Pharmacological interventions for pain in patients with temporomandibular disorders.

Mujakperuo HR, Watson M, Morrison R, Macfarlane TV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Oct 6;(10):CD004715. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004715.pub2. Review. PMID: 20927737 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

4. Fricton JR. Clinical care for myofascial pain. Dent Clin North Am. 1991 Jan;35(1):1-28. Review.

PMID: 1997346 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

HDSM-BWH CoEPES Small Group Guide for Medical, Dental, Nursing and Pharmacy Students

Background

This is a small-group session outline to follow-up on the on-line Case 2 module entitled “Mrs. Farley’s chronic temporomandibular joint and fibromyalgia pain.”

Case 2 is one of a series of 4 cases developed by the Harvard School of Dental Medicine and Brigham and Women's Center of Excellence in Pain Education (CoEPE).

The target student audiences are third and fourth year dental and medical students, 2nd year and masters level nursing programs, and pharmacy students entering clinical clerkships.

The focus of this case is to teach about temporomandibular disorder, fibromyalgia and myofascial pain, the impact of psychiatric comorbidities and gender differences in pain management, and pharmacologic, non-pharmacologic, and complimentary and alternative medicine pain management strategies.

The module will take approximately 1.5 hours to complete. The module will be subsequently discussed in one or more 45-60 minute small group sessions for each discipline led by an expert in the field who will follow the general discussion guidelines as outlined in the curriculum guide for each discipline. Following these small group sessions, students from all disciplines will be asked to consider reflective questions on a team-based approach to Mrs. Farley's care. This will be followed by an inter-professional workshop lasting approximately 1.5-2 hours led by a group of inter-professional experts using a curriculum guide with additional questions to frame the discussions. The case-based scenario can be used as a stand-alone module or integrated into an existing course, depending on the pain management education objectives.

For journal article references that pertain to this case, please consult the “Case 2 Final References” document.

Small Group leaders can choose to discuss appropriate learning points to review with students from the following learning objectives:

1) Define tools to assess and measure pain

2) Describe temporomandibular disorder (TMD) pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management

3) Describe fibromyalgia pathophysiology, diagnosis, and gender and psychological considerations

4) Delineate the risks, benefits and limitations of pharmacologic treatment options for TMD and fibromyalgia

5) Identify non-pharmacologic and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) pain management strategies

6) Discuss the roles of inter-professional providers in caring for a patient in pain

Small Group Discussion Topics and Questions

1) Assessing and Measuring Pain – a review:

In order to provide good care for your patients with pain, you need to be able to ask the right questions to help you better understand their pain.

- How can you remember what to ask about when assessing a patient’s pain?

- One example - OPQRST - Onset, Palliative/Provocative factors, Quality, Region/Radiation, Severity and Timing.

- What scales do you use to ask about pain severity?

- Numerical rating scale, Verbal descriptor scale, Faces pain scale, Functional pain scale

- Briefly address possible pitfalls and advantages/disadvantages of these

- What objective measures can you use to help assess pain?

- Although there is no “test” for pain, having the patient describe the impact of the pain on thoughts, feelings and actions; observing behaviors and responses to provocative maneuvers; and talking with significant others can help give a sense of the severity of the patient’s symptoms.

- What signs would you see in acute pain?

- Tachycardia, hypertension, diaphoresis, vasoconstriction, mydriasis (note, these are transient and unreliable measures).

2) Describe temporomandibular disorder (TMD) pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management:

- What symptoms are consistent with TMD?

- Ask the patient questions assessing their pain and/or limited range of motion (ROM) with jaw function. If the patient is pain-free during jaw function and does not have limited ROM, consider other orofacial pain disorders such as neuralgia, tooth pain, headache, etc.

How do you perform the TMD physical examination?

- The three parts of the TMD exam are ROM (pain-free and with pain), palpation of the masticatory structures, and auscultation (assessing joint sounds)

- After painful ROM, ask the patient to point to the location of their pain. Then, duplicate their pain with palpation. If preauricular pain occurs with vertical and lateral ROM, the source of pain is likely coming from the TMJ. TMJ arthralgia is usually sharp during jaw movement. Muscle pain is usually dull, aching, can be constant, and with somewhat limited ROM. Attempt to duplicate their muscle pain with palpation and determine if pain referral exists which is typical of myofascial pain.

- What are the diagnostic criteria for myofascial pain of the masticatory muscles?

- Dull aching pain

- Somewhat limited ROM

- Presence of trigger points consistent with

- A hypersensitive area

- Referred pain to another area associated with the patient’s symptoms

- Passive stretch (one can get the patient to open further by applying opening pressure on the mandible).

- What are the diagnostics criteria for TMJ arthralgia?

- To confirm diagnosis, the patient must have pre-auricular pain with at least two of these three maneuvers:

- Palpation

- ROM

- Joint Loading (upwards and/or distal pressure on the mandible)

- To confirm diagnosis, the patient must have pre-auricular pain with at least two of these three maneuvers:

Give a general explanation for TMD and it’s pathophysiology.

- TMD is a collection of musculoskeletal disorders of the head and neck involving the muscles of mastication and jaw joints. Included are headaches, neck, and ear pain influenced by jaw function

- Epidemiologic studies have shown that 40-70% of the population has signs and symptoms of TMD. However, 30 -45% of the population have jaw joint sounds. Approximately 7% of these persons will have symptoms severe enough to require treatment.

- Why do some people with signs and symptoms of TMD have pain and limited jaw opening while others do not? As with any pain patient, the answer is multifactorial and can include (but is not limited to) TMJ disc displacement, parafunctional habits, uncomfortable occlusion (bite), peripheral and/or central sensitization.

- Clenching (during the day and/or night), tooth grinding, and lip-biting are examples of parafunctional habits that contribute to TMD

- What causes a clicking TMJ? Adhesions in the joint capsule affect disc mobility causing the ligaments that hold the disk in place to become stretched. A click can occur when the condyle moves onto or off the disk

- Describe a standard treatment regimen for TMD.

- The goal of TMD therapy is to improve pain-free jaw ROM while giving the patient control of her TMD symptoms with the use of reversible therapies such as:

- Physical therapy (PT), appliance therapy, home exercise program, behavioral therapy, control of parafunctional habits (such as bruxism and daytime clenching), medication use (analgesics, sleep medications, muscle relaxants, anxiolytics), should be considered routine for initial therapy.

- One can prescribe non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or other analgesics for acute pain episodes; muscle relaxers for acute muscle pain; sleep medications can help control night-time parafunction; a 10-day regimen of anti-inflammatory medication or a Medrol dose pack for TMJ arthralgia

- 80% of patients with TMD will respond to standard TMD therapy. In the 20% who don’t respond, ensure you have made the correct diagnosis, the patient is complying with the treatment plan, and all contributing factors are being addressed

3) Describe fibromyalgia pathophysiology, diagnosis, and gender and psychological considerations

- How do you define fibromyalgia?

- Chronic pain syndrome characterized by widespread pain, allodynia and hyperalgesia

- What is allodynia? What is hyperalgesia?

- Allodynia is defined as pain due to a stimulus that does not normally cause pain (for example, light touch or clothing rubbing over skin is painful in someone who has allodynia).

- Hyperalgesia is defined as increased pain from a stimulus that normally causes pain (for example, extreme pain during placement of an intravenous line would be seen in someone with hyperalgesia; a person without hyperalgesia would feel discomfort and perhaps pain but not perceive it as extremely painful).

- Central amplification or sensitization is implicated in fibromyalgia and describes how the patient’s pain is maintained. How do you define central sensitization?

- You can kind of think of this as a heightened sense of pain because the central nervous system make-up has been altered from being bombarded with pain impulses.

- Think of the “volume control” setting example – patients with fibromyalgia perceive their pain volume is turned up very high in contrast to someone without fibromyalgia who might see a painful stimulus as not such a big deal…

- How would you diagnose fibromyalgia in a patient?

- Rely on criteria set forth by College of Rheumatology in 2010 that basically ensures that you exclude any other explanation for a patients’ pain and you also have to score accordingly on a widespread pain index (where the patient indicates where on body feels pain) and a symptom severity scale that looks at levels of fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, etc.

- Do you think Mrs. Farley definitely has fibromyalgia?

- No right or wrong answer, up for discussion, can look at 2010 criteria directly and attempt to tally her score

- How do you explain that patients with fibromyalgia also often have other pain problems like TMD, migraine, IBS, etc.?

- Central nervous system dysfunction affects general pain processing

- Increased pain signaling amplifies and perpetuates signaling in other pain disorders

- Believe patients when they have multiple pain complaints, as co-morbid pain complaints are a common phenomenon!

- How does gender affect pain?

- Evidence not clear… There is epidemiologic evidence that many pain disorders disproportionately affect women, such as TMD and fibromyalgia, but pain perception and experience is not unequivocally influenced by gender.

- Some evidence suggests that pain treatment responses may differ for women versus men

- How do psychological co-morbidities affect pain?

- Catastrophizing and depression are common in fibromyalgia and other pain disorders and are risk factors for adverse pain-related outcomes such as physical disability, increased severity of pain, enhanced pain sensitivity and other morbidities.

- If someone is depressed, they will likely have worse pain, and of course someone who is in pain may as a result be depressed so treating both simultaneously is very important to ensure recovery

- What is meant by the term catastrophizing?

- When one “catastrophizes” one has an irrational thought, believing that something is far worse than it actually is. It comprises a specific set of pain-related cognitive and emotional processes reflecting patients’ degree of helplessness when in pain, their tendency to ruminate about and magnify pain, and their propensity to magnify the threat value of pain.

4) Define pharmacologic treatment options for TMD and fibromyalgia

- Mrs. Farley was taking some of her family member’s opioids to help with her pain which she of course should not have done. Review the opioid risk assessment tool and what some screening questions can be to see if she is at risk for misusing opioids

- Note the 5 main categories in the left column (family and personal history of substance abuse, young age, history of sexual abuse, co-morbid psychological disease)

Opioid Risk Tool

| Female | Male | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Family history of substance abuse |

|

[1] [2] [4] |

[3] [3] [4] |

| Personal history of substance abuse |

|

[3] [4] [5] |

[3] [4] [5] |

| Age [mark box if age 16-45] | [1] | [1] | |

| History of preadolescent sexual abuse | [3] | [0] | |

| Psychological disease |

|

[2] [1] |

[2] [1]

|

Scoring: Low risk = 0-3, Moderate risk = 4-7, High risk = 8+

- Why would or wouldn’t you prescribe opioids for Mrs. Farley?

- Opioids are not the first-line treatment for fibromyalgia and especially for long-term therapy. There are many non-opioid alternatives she could try.

- List all possible pharmacologic agents you can think of to treat fibromyalgia. Group them into categories by class of medications

FDA-Approved Medications for Fibromyalgia

| Medication | Classification | Mechanisms of Action | Dosing | Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duloxetine (Cymbalta) | Antidepressant | Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | 30 mg orally once daily with titration to 60 mg/day | Nausea, xerostomia, insomnia, increase blood pressure |

| Milnacipran (Savella) | Antidepressant | Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | 12.5 mg orally on day 1, 12.5 mg twice daily on days 203; 25 mg twice daily on days 4-7, then 50 mg twice daily | Nausea, headache, increased blood pressure |

| Pregabalin (Lyrica) | Anticonvulsant | Reduces neuronal calcium currents by binding to the alpha-2-delta subunit of calcium channels | 75 mg orally twice daily with titration to 450 mg/day in divided doses | Dizziness peripheral edema, weight gain |

Non-FDA-Approved Medications and Non-Opioid Adjuvants

Non-FDA-approved medications and non-opioid adjuvants that can be helpful in treating Mrs. Farley’s pain.

| Medication/Adjuvant Therapy | Evidence to Support Use? | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Anticonvulsants (e.g., gabapentin [Neurontin]) | Yes | May reduce pain and impact of disease on activity and quality of life |

| Muscle relaxants (e.g., cyclobenzaprine [Flexeril]) | Yes | May improve symptoms and restorative sleep |

| Antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline) | Yes | Amitriptyline 25-50 mg at bedtime may be of benefit |

| Lidocaine injections | Yes | May be useful as trigger point injections |

| Topical agents (e.g., lidocaine) | No | No evidence to support use in fibromyalgia as disease presentation is often widespread |

| Acetaminophen | No | Not effective as monotherapy |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS, e.g., ibuprofen) | No | Limited evidence to support use as monotherapy |

| Intravenous lidocaine | No | Limited evidence to support use |

| Corticosteroids | No | None |

- Summarize your medication treatment plan recommendations for Mrs. Farley to help with her fibromyalgia and also TMD pain.

- Possible treatment plan:

- Mrs. Farley states that her current antidepressant is not helpful so switching to duloxetine (Cymbalta) may provide her with both pain relief and improved mood.

- A trial of an anticonvulsant (e.g. gabapentin, pregabalin) can also be considered in combination with duloxetine.

- Topical lidocaine patches may be helpful for localized pain, and Mrs. Farley can use an NSAID such as ibuprofen as needed for acute musculoskeletal pain.

- Possible treatment plan:

5) Identify non-pharmacologic and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) pain management strategies

- Let’s say Mrs. Farley is unwilling to pursue psychological care. How would you go about helping her realize that this a critical part of her care?

- Ask her why she is reluctant. Past experiences? Any bad experiences? Any fears? Worry about the Stigma? Concerned that her pain is “real”, not psychological? Any logistical constraints? How does she see the role of psychological management in her care?

- You could explain that in order to be able to treat her, you need input from a pain psychologist first, for instance.

- How do you think social and emotional stressors impact pain control?

- Negatively impact

- Patients often do not have adequate tools to cope with stressors

- Patients worry about planning get-togethers with family or friends out of fear they will have a “bad pain day”, and have to cancel.

- What techniques and non-pharmacologic tools can you recommend to help Mrs. Farley treat her pain and depression?

- Topical heat, topical cold, pacing activities, Counseling, sleep hygiene, massage, relaxation/imagery, meditation, music, acupuncture, PT. Find out what has worked for her in the past … even if to a small degree; and what she might be interested in trying. Plan specific times of the day to practice skill development for various techniques.

- Discuss how financial constraints may impact access to these therapies and what solutions you might have?

- Many therapies are not covered by insurance (behavioral medicine, PT, acupuncture, chiropractor, etc.)

- Alternative medicine clinics often offer initial evaluation that can be covered by insurance or group classes at discounted rates; and may be less expensive than traditional medical care.

- Referral to social work at your local hospital to investigate additional services patient may be eligible for

6) Discuss the roles of inter-professional providers in caring for a patient in pain

Taking care of patients in pain can be challenging for many reasons and working together with other healthcare providers can greatly benefit patients. In regards to Mrs. Farley, what are your thoughts on the following questions regarding inter-professional collaboration?

- What is your role as a student and soon-to-be professional in an inter-professional team?

- In regards to Mrs. Farley, what questions would you want to ask of a nurse taking care of his pain?

- In regards to Mrs. Farley, what questions should be asked of a dental consult?

- What questions would you have for her physicians?

- How can a pharmacist help manage his pain?

Inter-professional Questions to Consider

(may be repeated from above):

Distribute questions for students to answer prior to the inter-professional workshop.

1.) What unique perspectives can you contribute Mrs. Farley’s pain management plan?

2.) What are some of the limits of your perspective that can be enhanced by expanding the treatment team and getting others’ perspective on managing Mrs. Farley’s pain management plan?

3.) What are some ways to improve communication between members of the inter-professional team?

4.) What are the challenges of effectively and accurately sharing information between members of an inter-professional team?

5.) How do you ensure a cohesive patient care plan is communicated to the patient and family?

6.) What is your role as a student and soon-to-be professional in an inter-professional team?

7.) In regards to Mrs. Farley, what questions would you want to ask of a nurse taking care of his pain?

8.) In regards to Mrs. Farley, what questions should be asked of a dental consult?

9.) How can a pharmacist help manage pain?

10.) If the patient's primary care physician disagrees with your pain management regimen, how would you address this?

11.) What possible reasons exist for communication problems between physicians and other healthcare professionals?

12.) What benefits might result from improved communication?

13.) In what ways can you support good communication with other healthcare professionals?

14.) If patients appear to be “splitting” professionals (e.g. complaining about one professional to another), what strategy is best to manage behaviors and expectations?