Postoperative Pain Statistics for the US

- In a widely cited national survey of 250 recent postoperative patients:

- Pain was inadequately treated in approximately 50% of all surgical procedures

- More than 80% of patients experienced some form of postoperative pain

- 71% experienced moderate to severe pain

- Postoperative pain was the primary concern prior to surgery in 59% of the sample

Reference

Apfelbaum JL, et al. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2003;97:534-540.

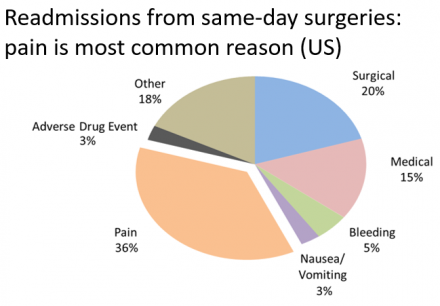

Readmissions From Same-Day Surgeries

In readmissions from same-day surgeries, pain is most common reason (US).

Incidence, Intensity and Duration of Postoperative Pain

| Surgical Procedure | Moderate pain, %* | Severe pain, %* | Mean duration (days) of moderately severe pain (range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrathoracic surgery: Sternotomy | 40-50 | 30-40 | 8 (5-12) |

| Intrathoracic surgery: Thoracotomy | 25-35 | 45-65 | 4 (3-7) |

| Gastric surgery: Abdominal aortic aneurysm resection | 20-30 | 50-75 | 4 (3-7) |

| Open cholecystectomy | 25-35 | 45-65 | 3 (2-6) |

| Lower abdominal surgery | 30-40 | 35-55 | 2 (1-4) |

| Appendectomy | 35-45 | 20-30 | 1 (0.5-3) |

| Inguinal and femoral herniotomy | 35-34 | 15-25 | 1.5 (1-3) |

| Head/neck/limb surgery | 35-45 | 5-15 | 1 (0.5-2) |

| Minor chest wall (mastectomy) and scrotal surgery | 35-50 | 10-30 | 1.5 (1-3) |

*Pain estimated by the amount of postoperative analgesics required and the time to first request for postoperative analgesia.

Filos KS, Lehmann KA. European Surgical Research. 1999;31:97-107.

Examples of Postoperative Pain

| Clinical Postoperative Pain | Example Surgery |

|---|---|

| Pain at rest | Any surgery |

| Pain with coughing | Thoracic, upper abdominal |

| Pain during ambulation | Abdominal |

| Pain during standing | Hip replacement |

| Pain with joint flexion | Total knee replacement |

| Pain with swallowing | Tonsillectomy |

Compliments of Timothy J. Brennan, PhD, MD, University of Iowa

Balancing Analgesic Safety and Effectiveness: Populations of Special Concern

- Obesity

- Increased risk for respiratory depression1-3

- may result from mechanical causes

- may result from erroneous practice of dosing opioids based on weight, leading to overdosing

- Therapeutic considerations

- start at low effective dose and titrate gradually

- monitor closely for side effects

- avoid basal rates with IV PCA2-4

- Increased risk for respiratory depression1-3

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Increases risk for respiratory depression1

- Often overlooked in association with opioid administration

- Assessment

- monitor sedation and respiratory status more frequently1-3

- sedation precedes respiratory depression, making it a sensitive indicator

- consider capnography or end tidal CO2 (EtCO2 ) monitoring

- Therapeutic considerations

- use lowest effective opioid dose; decrease dose if sedation is excessive2

- encourage multimodal therapy

- continue the use of C-PAP or BiPAP

- lying on side versus lying on back

References

- American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Neuraxial Opioids. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:218–230.

- Jarzyna D, et al. Pain Management Nursing. 2011;12:118-145.

- Macintyre PE, et al. Australian and New Zealand college of Anaesthetists and Faculty of Pain Medicine. Acute Pain Management: Scientific Evidence, (3rd ed.). 2010. https://www.anzca.edu.au/getattachment/4c3b03b7-52bf-4c10-9115-83d827c0fc38/Acute-Pain-Management-Scientific-Evidence.aspx

- Krenzischek DA, et al. Journal of Perianesthesia Nursing. 2008;23(1 suppl):S28-S42.

- Pasero C, McCaffery M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011

Test Your Knowledge

Patients undergoing a thoracotomy are at higher risk than other types of surgery for:

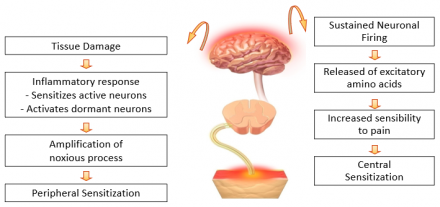

Chronic Pain Can Be Associated With Acute Pain that Wasn’t Effectively Controlled

- Acute pain leads to peripheral and central changes in nociception

- For some, these acute changes resolve with healing

- For others, these changes lead to life-long alterations in peripheral nervous system and central nervous system function thought to underlie chronic neuropathic pain syndromes

Acute Pain Management: Clinical Goals

- Prevent development of chronic pain syndromes

- significant number of postoperative patients develop chronic pain1-5

- Inguinal hernia: 5-63%

- Mastectomy: 11%-57%

- Thoracotomy: 5%-65%

- Amputation: 30%-85%

- severity of acute pain predicts chronic pain, although causal relationship is not fully established2,4

- significant number of postoperative patients develop chronic pain1-5

References

- Perkins FM, Kehlet H. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:1123–1133.

- Macrae WA. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2008;101:77-86.

- Macintyre PE, et al. Acute Pain Management: Scientific Evidence (3rd ed.). 2010.

- Schug SA, Pogatzki-Zahn EM. Pain Clinical Updates 2011;19:1-5.

- Niraj G, Rowbotham DJ. et al. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2011;107(1):25-9.

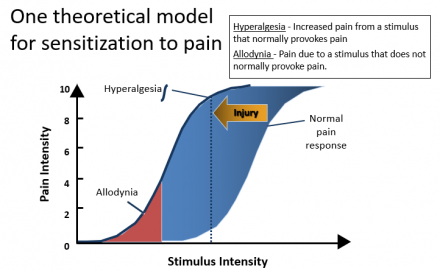

Understanding Consequences of Acute Pain

- Prevent development of chronic pain syndromes

- Poorly managed acute pain can lead to hypersensitization and persistent pain syndrome (PPS)1

Theoretical Model for Sensitization to Pain

References

- Gottschalk A, Smith DS. American Family Physician. 2001;63:1979-1984.

- Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of Chronic Pain. Seattle: IASP Press; 2011.

Chronic Post-Thoracotomy Pain

Definition

- “Pain that recurs or persists along [or near] a thoracotomy scar at least two months following the surgical procedure”1

- Most studies address pain one year after the procedure

Reference

- Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain. Seattle: IASP Press; 2011.

Characteristics

- Often predominately neuropathic pain, but can have myofascial characteristics in addition1

- Localized and radicular symptoms common2

- Burning or stabbing in quality2

- Pleuritic component can be present2

- Can be exacerbated by ipsilateral shoulder movement2

- Severe forms can result in complex regional pain syndrome including autonomic signs and symptoms3

References

- Wallace AM, Wallace MS. Anesthesiology Clinics of North America. 1997;15:353–370.

- Gerner P. Anesthesiology Clinics. 2008;26:355-vii.

- Guastella V, et al. Pain. 2011 152(1):74-81.

Persistent/Chronic Post-Thoracotomy Pain

Why bother with aggressive postoperative analgesia?

- Occurrence rate in this common surgical procedure 2nd only to limb amputation

- Pain associated with thoracic surgery is debilitating1

- Associated with a decrease in functional outcomes

- Characteristics common to development of other pain syndromes2

- sensory nerve dysfunction

- prolonged and intense noxious input to central nervous system

References

- Kinney MA, et al. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2012;93(4):1242-7.

- Buchheit T, Pyati S. Surgical Clinics of North America. 2012;92(2):393-407.

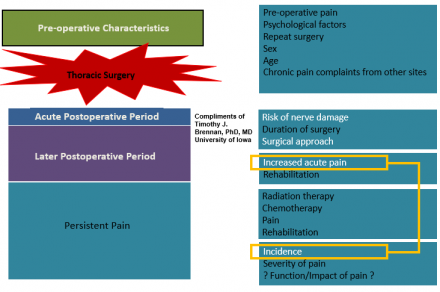

Possible Sources of Variation

Possible sources of variation for the incidence and severity of post-thoracotomy pain:

- Predisposing factors (e.g., gender, extent of resection, pre-operative pain)

- Surgical variables

- Analgesic variables

References

- Buchheit T, Pyati S. Surgical Clinics of North America. 2012;92(2):393-407.

- Althaus A, et al. European Journal of Pain. 2012;16(6):901-910.

Pre-Operative Characteristics

Summary

- Incidence about 60%

- Pain can persist for many years

- Large variability in reporting the incidence and severity of pain across studies

- Worse pain with:

- extent of surgery

- early intense pain

- Video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) may be same as open procedures

- Females may be at increased risk

More Information on Mechanisms of Post-thoracotomy Pain

Initial Pain Pathways

- Intercostal Nerves

- Majority of noxious input

- Phrenic Nerve (C3-5)

- Noxious input from pericardial pleura, mediastinum and diaphragm

- Shoulder pain decreased by phrenic1 but not suprascapular2 nerve block

- Vagal Nerve (CN X)

- Noxious input from lung parenchyma

References

- Scawn NDA, et al. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2001;93:260-264.

- Tan N, et al. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2002;94:199-202.

Intercostal Nerve Dysfunction Associated With Thoracotomy

Intercostal nerve dysfunction occurs at time of rib retraction in 100% of patients, often with adjacent dermatomes involved1

Intraoperative loss of intercostal nerve function was not associated with pain levels 3 months following surgery2

Intercostal nerve dysfunction is common 1 month following thoracotomy3,4

Extent of intercostal nerve dysfunction associated with pain levels over 1st postoperative week and at 1 month4

References

- Rogers ML, et al. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2002;21:298-301.

- Maguire MF, et al. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2006;29:873-879.

- Wildgaard K, et al. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2012;28(2):136-42.

- Benedetti F, et al. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 1998;115:841-847.

Intercostal Nerve Dysfunction: Other Aspects

Intraoperative nerve dysfunction not observed in single case where rib retraction not performed-but in all others1

Type of closure and duration of rib retraction affected nerve dysfunction2

Intercostal nerve dysfunction at one month was less with muscle-sparing thoracotomy compared with posterolateral incision3

Opioid analgesic therapy was less effective in those with intercostal nerve dysfunction at one month4

Duration of retraction associated with nerve dysfunction and allodynia in animals5

Reference

- Rogers ML, et al. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2002;21:298-301.

- Maguire MF, et al. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2006;29:873-879.

- Benedetti F, et al. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 1998;115:841-847.

- Benedetti F, et al. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 1997;64:207- 210.

- Buvanendran A, et al. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2004;99:1453- 1460.

Chronic Post-Thoracotomy Pain: Studies Documenting the Incidence (12-78%)

| Investigated | Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Long-term pain and activity during recovery from major thoracotomy… | No differences in 112 patients | Ochroch EA, et al. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1234-1244 |

| Thoracic epidural analgesia (TEA) with morphine for the prevention of post-thoracotomy pain syndrome | TEA with morphine does not prevent post-thoracotomy pain syndrome A survey of 159 patients |

Hu JS, et al. Acta Anaesthesiologica Sinica. 2000;38:195-200. |

| Epidural block … before surgery | Epidural block initiated prior to surgery reduced post-thoracotomy pain in 58 patients | Obata H, et al. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia 1999;46:1127-1132. |

| The effect of 3 different analgesia techniques … post-thoracotomy pain | Thoracic epidural analgesia (TEA) with pre-operative initiation was preferred technique. (n=69) | Senturk M, et al. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2002;94:11-15. |

Chronic Post-Thoracotomy Pain: Studies Documenting the Incidence (12-78%)

| Findings | Type of Study | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 54% reported 1 or more years (up to 4 years) | Retrospective | Dajczman E, et al. Chest. 1991;99:270-274. |

| 44% reported pain at 6 months | Retrospective | Kalso E, et al. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 1992;36:96-100. |

| 29% reported pain for more than 1 year (44% less than one year) | Retrospective | Landreneau RJ, et al. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 1994;107:1079-1085. |

52% reported pain at 1.5 years

|

Retrospective | Katz J, et al. Clinical Journal of Pain. 1996;12:50-55. |

| 61% reported pain | Retrospective | Bertrand PC, et al. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 1996;61:1641-1645. |

61% incidence of chronic post-thoracotomy pain 1 year post surgery

|

Retrospective | Perttunen K, et al. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 1999;43:563-567 |

| 67% of patients receiving thoracic epidural analgesia (TEA) post surgery alone experienced pain 6 months post surgery in comparison to 33% of patients who received TEA before and after surgery. | Retrospective | Obata H, et al. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 1999;46:1127-1132. |

| 78% patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), 63% postoperative TEA, 45% intraoperative/postoperative TEA at 6 months | Retrospective | Senturk M, et al. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2002;94:11-15. |

| 21% at 1 year, TEA | Retrospective | Ochroch EA, et al. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1234-1244 |

| 23% with PCA, 12% with TEA postop at 6 months, prospective | Retrospective | Tiippana E, et al. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2003;47:433-438. |

| 52% at 0.5-3.5 years, retrospective, TEA intraoperative/postoperative 48 hours, acute pain associated with long-term pain/more extensive procedures | Retrospective | Pluijms WA, et al. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2006;50:804-808 |

Chronic Post-Thoracotomy Pain: Video-Assisted Thoracotomies (VATS) vs. Open

- Landreneau et al. (1994) found non-significant difference in the incidence of pain 1 year post surgery when comparing open thoracotomy surgery (29%) and video-assisted thoracotomy surgery (22%).

- Bertrand et al. (1996) found equal frequency of extended post operative pain when comparing open thoracotomy surgery (61%) and video-assisted thoracotomy surgery (63%).

Reference

- Landreneau RJ, et. al. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 1994;107:1079-1085.

- Bertrand PC, et. al. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 1996;61:1641-1645.

Surgical Factors Thought to Reduce Pain from Thoracotomy

- Minimally invasive approaches

- VATS appears to have minimal effect on long-term pain

- acute pain may be less due to smaller incision and less rib retraction

- Muscle sparing vs classical posterolateral incision

- no benefit with respect to long-term pain

- inconsistent with data suggesting less intercostal nerve dysfunction one month after surgery

- Rib resection

- less pain with rib resection

- possibility of periosteal scarring

- Intercostal nerve preservation

- made difficult by anatomic variation in course of nerves

- Method of rib approximation at closure

- suture to avoid nerve entrapment

- devices to improve stability

What is Multimodal Analgesia and Why is This Strategy Important?

Multimodal Strategy: Combining Classes of Agents

- Foundation of multimodal analgesia is the combination of two or more medications with different modes of action

- Generally involves adding at least one but often more than one new class of drug to an opioid

- NSAID blocks production of inflammatory mediators

- Anticonvulsant or antidepressant to inhibit propagation of pain impulses

- Generally involves adding at least one but often more than one new class of drug to an opioid

Reference

Kehlet H, et al. Practice & Research Clinical Anesthesiology. 2007;21:149-159.

Analgesic Strategies: Role of Common Agents

- Acetaminophen: Decreases shoulder pain when added to thoracic epidural analgesia (TEA)1

- NSAIDs reduce opioid use postoperatively2,3

- Opiates: Systemic as well as neuraxial, can decrease allodynia in animal model of thoracic surgery. Smooth transition from TEA to systemic opioid is importance 4

- Ketamine/dextromethorphan: shown to enhance epidural analgesia and patients had reduced in pain up to 3 months after thoracotomy5, and reduced hyperalgesia/allodynia at 1 month6

- Gabapentin: Systemic and neuraxial administration reduced allodynia in animal model of thoracotomy4 some studies now support its use with persistent pain following thoracic surgery7,8

- Clonidine (neuraxial): Reduced allodynia in animal model of thoracotomy when added to continuous paravertebral block following thoracotomy9

- Neostigmine (neuraxial): Reduced allodynia in animal model of thoracotomy4

References

- Mac TB, et al. Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia. 2005:19;475-478.

- Rhodes M, et al. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 1992;103:17-20.

- Pavy T, et al. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1990;65:624-627.

- Buvanendran A, et al. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2004;99:1453-1460.

- Suzuki M, et al. Anesthesiology, 2006;105:111-119.

- Ozyalcin NS, et al. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2004;93:356-361.

- Sihoe AD, et al. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2006;29:795-759.

- Solak O, et al. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2007;32:9-12.

- Bhatnagar S, et al. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care 2006;34:586-591.

Implementing Multimodal Therapy: Classes of Analgesics

| Class of Agent | Opioids |

|---|---|

| Target | Mu opioid receptors |

| Clinical Utility | Mainstay for moderate to severe pain |

| Clinical Concerns |

Sedation Respiratory depression Constipation Nausea/vomiting Potential for tolerance |

Conversion Chart for Selected Opioids

| Opioid | IV (mgs) | PO (mgs) |

|---|---|---|

| Morphine | 10 | 30 |

| Hydromorphone | 1.5 | 7.5 |

| Fentanyl | 0.1 | Transmucosal only |

| Oxycodone | NA | 20 |

| Levorphanol (Levo-Dromoran) | 2 acute | 4 acute |

| Oxymorphone | 1 | 10 |

Codeine, hydrocodone and fentanyl patch not listed. Buprenorphine had nor oral dose given and 0.3 listed for IV. I left this is red since it was a change. All the rest were the same.

Conversions used with permission: American Pain Society. Principles of analgesic use in the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain. 6th ed. (pp. 19–21). Chicago, IL: American Pain Society, 2008.

Opioid Analgesics

- Opioids regulate pain throughout the pathway in the

- Periphery

- To inhibit calcium influx and activation of nociceptors

- Spinal cord

- To prevent release of neurotransmitters

- Ascending pathway

- To block transmission

- Brain

- To turn on the descending pathways

- Periphery

Systemic Opioids for Managing Mrs. Smith’s Pain

Systemic Opioids

- Opioids are often used to treat acute pain

- While effective, they have significant risk for harm, including risk of respiratory arrest and death, as well as diversion and non-medical use

- Extreme care should be used when administering opioids to balance effective pain control with risk of harm

Opioids for Acute Pain Management General Principles

- In the management of acute pain, one opioid is not superior over others, but some opioids are better in some patients

- The incidence of clinically meaningful adverse effects of opioids is dose-related

- Supplemental oxygen in the postoperative period improves oxygen saturation and reduces tachycardia and myocardial ischemia

- “In adults, patient age, rather than weight is a better predictor of opioid requirements, although there is a large inter-patient variation”1

- For acute or worsening pain, always start therapy or make changes in therapy with short acting opioids before changing any long acting dose or basal infusion rate

- Assessment of sedation level is a more reliable way of detecting early opioid-induced respiratory depression than a decreased respiratory rate2

Reference

- Macintyre PM, Schug SA. Acute pain management: a practical guide. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2007. p. 68.

- Jarzyna D, et al. Pain Management Nursing. 2011;12:118-145.

- Macintyre PE, et al. Australian and New Zealand college of Anaesthetists and Faculty of Pain Medicine. Acute Pain Management: Scientific Evidence, (3rd ed.). 2010. https://www.anzca.edu.au/getattachment/4c3b03b7-52bf-4c10-9115-83d827c0fc38/Acute-Pain-Management-Scientific-Evidence.aspx

Implementing Multimodal Therapy: Classes of Analgesics

| Class of Agent | Opioids |

|---|---|

| Target | Mu opioid receptors |

| Clinical Utility | Mainstay for moderate to severe pain |

| Clinical Concerns |

Sedation Respiratory depression Constipation Nausea/vomiting Potential for tolerance |

Classes of Pain Medications: Nonopioids

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS)

- examples: celecoxib, ketorolac

- anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects

- principal mechanism of action: inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis

- activity at peripheral nociceptors and in spinal cord

- side effects due in part to selectivity for cyclooxygenase-2

- impaired hemostasis (nonselective)

- GI irritation/bleeding (nonselective)

- cardiovascular risk

- renal toxicity (Be sure to check renal function prior to administration and during therapy, if warranted.)

- Acetaminophen

- analgesic but not anti-inflammatory

- less potent than NSAIDs

- lacks adverse effects of NSAIDs

- hepatotoxicity in overdose

- caution with acetaminophen dosing (especially in combination analgesics) - not to exceed 4000 mg daily for IV (FDA, January 24, 2013)

NSAIDs

Test Your Knowledge

Which of the following is a true statement?

NSAID Analgesia Efficacy

- Single doses of NSAIDs are effective in the treatment of pain:

- After surgery

- Low back pain

- Renal colic

- When given in combination with opioids after surgery, NSAIDs result in better pain relief and reduce opioid consumption

- the opioid-sparing effect is associated with a reduced or comparable incidence of adverse opioid-related effects

- the addition of an NSAID to acetaminophen also improves pain relief

- NSAIDs, when not contraindicated, should be included in multimodal analgesia

Reference

Macintyre PE, et al. Australian and New Zealand college of Anaesthetists and Faculty of Pain Medicine. Acute Pain Management: Scientific Evidence, (3rd ed.). 2010. https://www.anzca.edu.au/getattachment/4c3b03b7-52bf-4c10-9115-83d827c0fc38/Acute-Pain-Management-Scientific-Evidence.aspx

NSAID-Induced Asverse Effects

- Short-term use of NSAIDs are associated with:

- interference with platelet function

- peptic ulceration

- bronchospasm in individuals who have aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease

- renal impairment (rare)

- check baseline renal function prior to administration

- The risk and severity of NSAID-induced adverse events is increased in older adults

Reference

Macintyre PE, et al. Australian and New Zealand college of Anaesthetists and Faculty of Pain Medicine. Acute Pain Management: Scientific Evidence, (3rd ed.). 2010. https://www.anzca.edu.au/getattachment/4c3b03b7-52bf-4c10-9115-83d827c0fc38/Acute-Pain-Management-Scientific-Evidence.aspx

Acetaminophen

Test Your Knowledge

Acetaminophen(choose all that apply):

Acetaminophen Overview

- Acetaminophen is an effective adjunct to opioid analgesia

- opioid requirements are reduced by 20-30% when administered on a scheduled basis

- use of oral acetaminophen (1 g q 4 hours) in combination with IV PCA morphine lowered pain scores, shortened the duration of PCA use and improved patient satisfaction

- The addition of an NSAID to acetaminophen further improves efficacy

- Acetaminophen has fewer adverse events than NSAIDs, and can be used when NSAIDs are contraindicated due to asthma and peptic ulcer disease1

- Acetaminophen should be used with caution or in reduced doses in patients with active liver disease, alcohol-related liver disease and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency1

- the rate of reactive metabolite production can result in centrilobular hepatocellular necrosis, occasionally with acute renal tubular necrosis1

- Be mindful of total daily acetaminophen dose recommendations

- exercise caution, there are over 600 over the counter medications containing acetaminophen, dosing of all medications is not to exceed 4000 mg daily2

References

- Macintyre PE, et al. Australian and New Zealand college of Anaesthetists and Faculty of Pain Medicine. Acute Pain Management: Scientific Evidence, (3rd ed.). 2010. https://www.anzca.edu.au/getattachment/4c3b03b7-52bf-4c10-9115-83d827c0fc38/Acute-Pain-Management-Scientific-Evidence.aspx

- FDA consumer update, “Don’t Double Up on Acetaminophen” January 24 2013. Accessed on August 1, 2013 at http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm336581.htm

Classes of Pain Medications: Local Anesthetics

Examples: lidocaine, bupivacaine.

- Modulate sodium channels

- When administered peripherally, may produce differential—also known as sensory—block

- interrupts some nerve conduction, but leaves motor function unaffected

- some nerves are more readily blocked than others, depending on size and myelination

- Interrupts pain input at the nerve roots

- Associated with few adverse effects

Reference

Brunton LL, Lazo SS, Parker KL. Goodman & Gillman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 11th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2006.

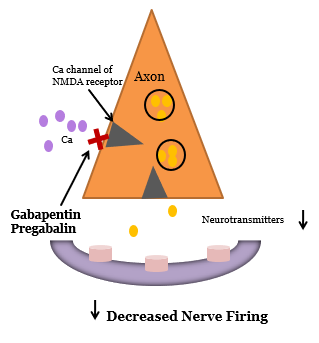

Anti-Convulsants

- Calcium channel modulation of the NMDA receptor

- Gabapentin (Neurontin®):

- Sedation and cognitive slowing may limit titration

- Peripheral edema – rare

- Pregabalin (Lyrica®):

- More rapid titration possible

- Costs more than generic gabapentin

Perioperative Use of Anti-Anticonvulsants for Pain

- Frequently used in combination with multimodal analgesic regimens

- Dosing considerations:

- Gabapentin*:

- pre-operative dose 100 mg PO BID or TID and/or 300 mg the morning of surgery

- postoperative dose can be maintained at 300 mg TID with titration as tolerated to avoid over sedation

- posing can continue up to 1 or 2 months after surgery

- Pregabalin*

- pre-operative dose 50 mg to 150 mg daily or 100 BID

- 100 PO before surgery

- postoperative dose can be maintained or increased as tolerated (maximum dose 600 mg daily)

- more efficiently absorbed through GI tract

* Gabapentin and pregabalin are not FDA approved for this purpose but are supported by strong clinical trial evidence.

Reference

Clarke, H et al. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2012;115(2):428-442.

Macintyre PE, et al. Australian and New Zealand college of Anaesthetists and Faculty of Pain Medicine. Acute Pain Management: Scientific Evidence, (3rd ed.). 2010. https://www.anzca.edu.au/resources/college-publications/acute-pain-management/apmse5.pdf

Implementing Multimodal Therapy: Classes of Analgesics

| Class of Agent | Opioids | NSAIDs | Local anesthetics | Anticonvulsants | Antidepressants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target | Mu opioid receptors | Prostaglandins | Sodium channels | Sodium and calcium channels |

Serotonin Norepinephrine |

| Clinical Utility | Mainstay for moderate to severe pain | First-line adjunct to opioids | Differential (sensory) blockade | Becoming first-line adjunct in acute pain and first-line therapy for chronic pain |

First-line therapy in chronic pain Limited application in acute pain |

| Clinical Concerns |

Sedation Respiratory depression Constipation Nausea/vomiting Potential for tolerance |

Renal impairment Liver impairment GI bleeding/ulcers Hemostasis CV risk |

Allergic reactions | CNS-related adverse effects, including dizziness, sedation, and fatigue | Limited analgesic effect of serotonin-specific agents |

Analgesic strategies: Role of Common Agents

- Acetaminophen: Decreases shoulder pain when added to thoracic epidural analgesia (TEA)1

- NSAIDs reduce opioid use postoperatively2,3

- Opiates: Systemic as well as neuraxial, can decrease allodynia in animal model of thoracic surgery. Smooth transition from TEA to systemic opioid is importance 4

- Ketamine/dextromethorphan: shown to enhance epidural analgesia and patients had reduced in pain up to 3 months after thoracotomy5, and reduced hyperalgesia/allodynia at 1 month6

- Gabapentin: Systemic and neuraxial administration reduced allodynia in animal model of thoracotomy4 some studies now support its use with persistent pain following thoracic surgery7,8

- Clonidine (neuraxial): Reduced allodynia in animal model of thoracotomy when added to continuous paravertebral block following thoracotomy9

- Neostigmine (neuraxial): Reduced allodynia in animal model of thoracotomy4

References

- Mac TB, et al. Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia. 2005:19;475-4784.

- Rhodes M, et al. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 1992;103:17-20.

- Pavy T, et al. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1990;65:624-627.

- Buvanendran A, et al. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2004;99:1453-1460.

- Suzuki M, et al. Anesthesiology, 2006;105:111-119.

- Ozyalcin NS, et al. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2004;93:356-361.

- Sihoe AD, et al. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2006;29:795-759.

- Solak O, et al. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2007;32:9-12.

- Bhatnagar S, et al. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care 2006;34:586-591.

Multimodal Strategy: Additional Clinical Evidence

- Significant clinical trial evidence shows that an opioid plus another class of analgesic agent better controls pain than opioids alone

- Addition of an NSAID reduced postoperative morphine use, decreased opioid-induced adverse effects, and had other significant benefits1-5

- Opioid plus gabapentin or pregabalin reduced opioid requirements, pain, and opioid-induced adverse effects2,6,7

References

- Elia N, et al. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:1296-1304.

- Eipe N, et al. Systematic Reviews. 2101;1:40.

- Rawlinson A et al. Evidence-based Medicine. 2012 Jun;17:75-80.

- De Oliveira GS Jr, et al. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2012;114(2):424-433.

- Zemmel MH. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Anesthetists. 2006;74:49-60.

- Mathiesen O, et al. BMC Anesthesiology. 2007;7:6.

- Tiippana EM et al. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2007;104:1545-1556.

Multimodal Therapy: Implications for Practice

- Effective and safe practices with multimodal therapy require that nurses and physicians:

- understand the rationale for combining analgesics

- be knowledgeable about classes of analgesics

- mechanisms of action and pharmacodynamics

- synergistic efficacy and adverse effects

- ensure timely administration, avoiding gaps in all analgesics

- institute assessment and monitoring practices for safe patient care

- aggressively manage adverse effects of analgesics

References

- Young A, Buvanendran A. Anesthesiology Clinics. 2012;30(1):91-100.

- Krenzischek DA, et al. Pain Management Nursing 2008;9(1 Suppl):S22-32.

- Dunwoody CJ, et al. Pain Management Nursing. 2008;9(1 Suppl):S11-21.

Postoperative Pain Management

Postoperative pain management begins prior to surgery. The first step is patient assessment.

- Patient assessment starts BEFORE surgery and should lead to the development and implementation of an integrated pain treatment plan

- History of pre-operative pain and current outpatient opioid use are important factors in selecting appropriate post-op therapy

- Many programs are moving to adding pain therapy as part of the anesthetic plan

- Complex pain patients should be considered for pre-operative anesthesiology consultation

- Screen for current or history of substance abuse

Patient Assessment

- Frequent monitoring of respiratory rate for 1 minute and sedation level are critical, especially in the first 24 hours after surgery1,2

- Two commonly used validated sedation scales include:

- Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale (RASS)3

- Can be accessed: http://w3.rn.com/news/news_features_details.aspx?Id=34558

- Pasero Opioid-Induced Sedation Scale (POSS)4

- Copy available in the Resource Center.

- Assessment of the patient’s pain should be integrated into the care of the patient at least daily but often more frequently

- Patient assessment includes assessment of the patient’s report of pain intensity

- Assessment should include:

- use of a valid measurement tool

- careful evaluation of the patient’s symptoms beyond the pain intensity report

- evaluation for adverse side effects

References

Rathmell, JP, et al. Regional Anesthesia Pain Medicine. 2006;31(4 suppl 1):1–42.

Jarzyna D et al. Pain Management Nursing. 2011;12:118-145.

Sessler CN, et al. Critical Care. 2008;12 Suppl 3:S2-S13.

Nisbet AT, Mooney-Cotter F. Pain Management Nursing. 2009;10(3):154-164.

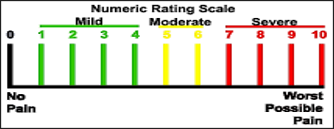

Pain Assessment Tools

Numeric Rating Scale

- Tool must be appropriate to patient and setting

- numerical rating scale (NRS)

- Ask the patient to rate their pain on a scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable)

- alternative assessment tools when NRS is not appropriate

- asking if the pain is tolerable at its current level can be helpful

- verbal descriptive scale (VDS) can also be used in addition to 0-10 scale

- visual analogue scale (VAS - a 10-cm-long horizontal line with “no pain” on the left and “worst pain imaginable” on the right) is harder to collect

- numerical rating scale (NRS)

Reference

Powell RA, et al. Pain History and Pain assessment. in Kopf A, Patel N. Guide to pain management in low-resource settings. 2010;71.. This chapter has been reproduced with permission of the International Association for the Study of Pain® (IASP). The chapter may NOT be reproduced for any other purpose without permission.

Don’t Treat a Number, Treat the Patient

- the NRS is a unidimensional pain intensity measurement tool

- a good provider integrates the information the patient provides with other patient assessment information they obtain

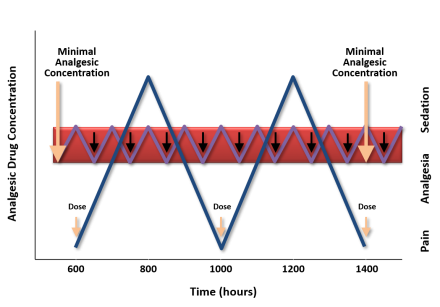

Dosing Regimen Definitions

- P.R.N. – as needed

- Scheduled nurse administered dosing

- Patient-Controlled Analgesia (PCA)

- Continuous infusion (basal rate - only appropriate in opioid tolerant patients)

PCA vs Intermittent Dosing

Reference

Ferrante FM, Orav EJ, Rocco AG, and Gallo J. “A Statistical Model for Pain in Patient‐Controlled Analgesia and Conventional Intramuscular Opioid Regimens.” Anesthesia & Analgesia. 1988;67:457-461. This figure has been reproduced with permission. Copyright © 1988

IV PCA: General principles

- Patient Controlled Analgesia (PCA) provides better analgesia than conventional parenteral opioid regimens

- Patient preference for PCA is higher when compared with conventional regimens

- PCA does not lead to lower opioid consumption, reduced hospital stay or a lower incidence of opioid-related adverse effects compared with traditional methods of intermittent parenteral opioid administration

- There is little evidence that one opioid via PCA is superior to another with regard to analgesic or adverse effects in general

- on an individual patient basis one opioid may be better tolerated than another at an equianalgesic dose

- even in opioid-naïve patients there is a large variability in opioid response so all patients will need to be titrated to effect

- basal infusions are appropriate in opioid tolerant patients but should not be used initially in opioid-naïve patients

- The addition of a background basal infusion to PCA does not improve pain relief or sleep, or reduce the number of PCA demands

- The risk of respiratory depression is increased when a background basal infusion is used

- Basal infusions should not be used in opioid-naïve patients

References

- Macintyre PE, et al. Australian and New Zealand college of Anaesthetists and Faculty of Pain Medicine. Acute Pain Management: Scientific Evidence, (3rd ed.). 2010. https://www.anzca.edu.au/resources/college-publications/acute-pain-management/apmse5.pdf

- Rathmell, JP et al. Regional Anesthesia Pain Medicine. 2006;31(4 suppl 1):1–42

Basal Infusion in Opioid-Tolerant Patients

- Basal infusions have an important role in the care of patients who are opioid-tolerant but should not be used in opioid-naïve

- At least 80% of the total daily dose taken at the time of admission should be provided in the basal rate

- For PCA to be successful, the demand dose should produce effective or acceptable analgesia with a single demand

Reference

Mitra S, Sinatra RS. Anesthesiology 2004;101:212-227.

Effectiveness of PCA

- 59.8-68.6% success rate. Higher success is related to the skill of the patient care team1

- 30-40% of patients will not have adequate analgesia with PCA alone

- IV PCA does not alter the surgical stress response

- Risks can include:

- adverse events such as nausea, vomiting, and pruritus2

- more seriously, unintended advancing sedation and respiratory depression, especially with inappropriate initiation or level of the basal rate3

References

- Macintyre PE. Anesthesiology Clinics of North America. 2005;23:109–123.

- Dolin S, Cashman J. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2005;95(5):584-591.

- Cashman J, Dolin S. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2004;93(2):212-223.

PCA-Related Medication Errors

- Almost ALL mishaps associated with the use of PCA opioids is due to human error1-3

- inappropriate drug selection

- inappropriate use of basal infusion in opioid-naïve patients

- inappropriate drug dose for specific opioid

- error while programming the PCA device and during administration1,2

- not accounting for other sedatives in choice of opioid dose

References

- Hicks RW, et al. American Journal of Health System Pharmacists. 2008;65:429-440.

- Schein JR et al. Drug Safety. 2009;32:549-559.

- Moss J. Joint Commission Journal of Quality and Patient Safety. 2010;36(8):359-364.

Error Prevention with PCA

- Schein et al. outline numerous error reduction strategies that form the basis for safe practices with IV PCA administration1

- system-wide changes to include computerized provider order entry (CPOE)

- enhanced technology such as bar coding to ensure that the right drug gets to the right patient and smart pump devices that impose safeguards for medication safety

- Avoid potential errors by:2

- staff education

- written information on hydromorphone and fentanyl posted on all patient care units to show differences in dosing compared to morphine

- detailed policies and procedures for prescribing and administering PCA

- standardized concentration for all opioids

- independent double-checks on initiation of therapy and with all setting changes

References

- Schein JR, et al. Drug Safety. 2009;32:549-559.

- Moss J. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2010;36(8):359-364.

PCA by Proxy

- Is the activation of the device in the administration of medication by someone other than the patient

- This could ultimately lead to unintended advancing sedation and respiratory depression1,2

- The American Society for Pain Management Nursing published a position paper to address unauthorized and authorized PCA by proxy2

- examines the ethical and safety issues surrounding this practice

- promulgates consensus-based guidelines for selecting an authorized agent, when appropriate

- recommends proper education and parameters around responsibilities for ensuring safety and effectiveness of the therapy

References

- Rathmell, JP et al. Regional Anesthesia Pain Medicine. 2006;31(4 suppl 1):1–42.

- Wuhrman E, et al. Pain Management Nursing. 2007; 8:4-11.

Opioids Should Be Prescribed Appropriately and With Caution

- There are serious risks of harm associated with opioid pain therapy that is not carefully planned

- Opioid-related adverse events are common in hospitalized patients, and they can increase the length of stay and total hospital costs

References

- Kessler ER, et al. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33(4):383-391.

- Oderda GM, et al. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2003;25:276-283.

Well Described Opioid-Induced Adverse Side Effects

- Ventilatory/respiratory depression

- Sedation

- Pruritus

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Urinary retention

- Constipation and/or ileus

- Acute tolerance

References

- Benyamin R, et al. Pain Physician 2008: Opioid Special Issue. 2008;11:S105-S120.

- Swegke JM, Logeman C. American Family Physician. 2006;74:1347-1354.

Adverse Effect Management

| Adverse Effect | Tolerance | Management |

|---|---|---|

| Constipation | No | Stool softener (docusate) + motility agent (senna) |

| Nausea/Vomiting | Yes (3-5 days) | Antiemetics (prochlorperazine) |

| Sedation/Confusion | Yes (3-5 days) | Monitor patient |

| Respiratory depression | Yes (risk is dose dependent) | Reversal agent (naloxone) |

| Pruritus | Yes (3-5 days) | Antihistamines (diphenhydramine, loratadine) |

| Bradycardia | NA | Only problematic if patient symptomatic |

| Allergy | NA | DC current opioid; switch to another opioid |

When is the Patient at the Highest risk?

- The first 24 hours1,2 after surgery represents “a high-risk period for a respiratory event” as a result of opioid use3

- Opioid-related sedation seems to be the highest within the first 4 hours after discharge from the post anesthesia care unit(PACU)4

- When basal infusions too high or are used in opioid-naïve patients

References

- Pasero C. Journal of Perianesthesia Nursing. 2013;28(1):31-7.

- Jarzyna D, et al. Pain Management Nursing. 2011;12:118-145.

- Weinger MB. APSF Newsletter. 2006;21:61-63.

- Taylor S, et al. American Journal of Surgery. 2003;186:472-475.

Do Not Treat the Number: Treat the Patient

When a policy to titrate opioids to specific NRS number was instituted at a medical center, the incidence of opioid-induced adverse reactions increased from 11 to 25 per 100,000 inpatient days.

Assessment of sedation level is a more reliable way of detecting early opioid-induced respiratory depression than a decreased respiratory rate.

References

- White PF, Kehlet H. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2007;105:10-12.

- Vila, Jr H, et al. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2005;101:474-480.

The use of Acupuncture in Treating Postoperative Pain

The History of Acupuncture

- An ancient form of therapy originated from the Traditional Chinese Medicine

- Acupuncture uses thin, sterile needles placed at specific points.

- Effect sometime augmented by heat or electro-stimulation

- In animal models, acupuncture stimulates endogenous opioid secretion

- Using functional brain imaging, acupuncture stimulation influences human brain regions of limbic system, hypothalamus, and brainstem networks.

References

- Mao JJ, Kapur R. Primary Care. 2010;37:105-117.

- Han JS. Neuroscience Letters. 2004;361:258-261.

- Huang W, et al. Plos One. 2012;7: e32960.

Acupuncture for Postoperative Pain

- Meta-analysis by Sun et al. (2008)

- 15 RCTs comparing acupuncture to sham controls

- Compared to controls, Acupuncture reduced

- Postoperative pain intensity at 8 and 72 hours

- Opioid consumption

- Incidence of opioid-related adverse effects (i.e. nausea, sedation, pruritus, and urinary retention)

Sun 2008 in British Journal of Anaesthesia – 15 RCTs included in meta-analysis. Visual analogue scale used to measure postop pain. They saw a reduction in opioid consumption ranged from 21% to 29%, which is clinically significant. Reduced opioid-related AE were nausea, pruritus, dizziness, sedation, and urinary retention.

Reference

Sun Y, et al. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2008;101:151-160.

Analgesic Effect of Electro-Acupuncture in Post-Thoracotomy Pain: A Prospective Randomized Trial

- 25 patients with operable non-small cell lung carcinoma

- 30-minute acupuncture sessions each day for the first 7 postoperative days

- Lower PCA morphine requirements on postoperative day 2 in the EA group

- Trend for lower average visual analogue scale (VAS) pain scores from postoperative day 2 to day 6 in the EA group (not significant)

Double-blind RCT in Hong Kong

Methodology

The points selected were the LI 4, GB 34, GB 36, and TE 8 points ipsilateral to the side of the thoracotomy, and which are recognized to influence the chest wall and upper body. Sham acupuncture used pseudo-stimulation and a blunt tip needle to mimic pricking without actual skin piercing (Figure).

Outcomes Measured

Average visual analog scale pain scores and the cumulative PCA morphine usage were the primary outcome measures

Results

First off, it is safe! There was no mortality, complication, or adverse reaction (such as infection and bleeding) related to acupuncture in both groups.

Reference

Wong RH, et al. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2006;81:2031-2036.

Test Your Knowledge

Which of the following answers is NOT true?

Acupuncture use in post-operative setting can: