The following material can be used by instructors for small group review.

Pain and Addiction

Always document: a differential diagnosis and comprehensive treatment plan.

Addiction and Misuse: Definitions

- Addiction = chronic + craving + compulsion – concern - control

- Tolerance: decreased analgesic efficacy at a fixed dosage

- Withdrawal: signs or symptoms after abrupt reduction or discontinuation of agonist or after antagonist administration

- Physical dependence: physiological adaptation to presence of drug which is manifested by withdrawal signs or symptoms when dosage lowered or stopped or an antagonist is administered

- Chemical coper: patient who self-escalates opioid use to deal with emotional stress to the exclusion of nonpharmacological therapies such as psychotherapy and development of coping skills

- Pseudoaddiction: seeking of additional pain medications due to inadequately treated pain

Abuse, Diversion, Treatment Failure

- Substance abuse: use of illegal drugs or the use of prescription or over-the-counter drugs or alcohol for purposes other than those for which they are meant to be used, or in excessive amounts; substance abuse may lead to social, physical, emotional, and job-related problems. (National Cancer Institute definition)

- Diversion: transfer of a controlled substance from a lawful to an unlawful channel of distribution (Uniform Controlled Substances Act definition)

- Treatment failure: lack of efficacy, as defined by inadequate analgesia, lack of improvement in function, aberrant drug behaviors or increased adverse effects, despite an adequate trial

- Ceiling effect: increasing dosage of pain reliever above its ceiling does not result in increased analgesia; opioid agonists do not have a ceiling effect however a partial agonist like suboxone has a ceiling effect both for analgesia and respiratory depression

The four A’s: Balanced Analgesia

- Activity

- Mobility

- Ability to work, school

- Sleep

- Relationships: family. friends

- Enjoyment of life

- Analgesia

- Pain intensity on average

- Pain intensity at worst

- How often does pain reach a maximum intensity

- Change in quality or location

- Adverse effects

- Constipation

- Nausea, Vomiting

- Cognitive decline, clouding

- Loss of libido

- Weight loss or gain

- Sleep disruption, fatigue

- Abuse/aberrant behavior

- Urine drug-tox failure/refusal

- Lost or stolen prescription

- Request for name brand

- Behavior or appearance

- Dose escalation w/o consultation

- Refusal of nonpharm. treatment

Recognizing Opioid Overdose

Opioid OVERDOSE mnemonic: “MORPHINE”

- Myosis

- Obtundation (sedation)

- Respiratory suppression

- Positive toxicology

- Hypotension

- Infrequency of bowel/bladder function, e.g., constipation

- Nausea

- Evidence of addiction, e.g., skin popping

Recognizing Opioid Withdrawal

Opioid WITHDRAWAL mnemonic: ‘FLAPPY HANDS’:

- Fever and chills

- Lacrimation

- Agitation

- Piloerection

- Pupillary dilation

- Yawning

- Hypertension and tachychardia

- Aches

- Nausea

- Diarrhea

- Sweating

Opioids or Opiates?

- Opium – mixture of alkaloids obtained from seed capsules of the opium poppy

- Opiates – naturally occurring alkaloids such as morphine and codeine and synthetic alkaloids such as heroin and oxycodone which binds to any or all of the opioid receptor subtypes

- Opioids – any compounds with binds to any or all of the opioid receptor subtypes including peptides such as endorphins and enkephalins and naturally-occurring, synthetic or semi-synthetic alkaloids such as morphine, fentanyl or hydromorphone

- Opioid receptors – the three classes of receptors, mu (μ), kappa (κ) and delta (λ), found through CNS and peripheral tissues to which endogenous opioid peptides bind

DEA Schedule Definitions

Drugs are categorized as either unscheduled or scheduled controlled substances. There are five schedules of controlled substances; lower schedule number means higher abuse potential.

- Schedule I: high abuse potential, substance has no medical use in treatment in the U.S.

- Schedule II: high abuse potential but substance has currently accepted medical use in U.S.; use may lead to severe psychological or physical dependence

- Schedule III: abuse potential is less than schedules I & II; only moderate to low risk of psychological or physical dependence

- Schedule IV: abuse potential is less than schedule III; only limited risk of psychological or physical dependence relative to substances in schedule III

- Schedule V: abuse potential is less than schedule IV; only limited risk of psychological or physical dependence relative to substances in schedule IV

Agonist, Antagonist

- Agonist – compound which binds to receptor and elicits a full characteristic pharmacological response

- Partial agonist – compound which binds to receptor and elicits only a limited characteristic pharmacological response

- Antagonist – compound which binds to receptor and does not give a pharmacological response

Small Group Cases

Case 1: New‐Onset Severe Lumbar Pain

Mrs. R., a 55‐year‐old breast cancer survivor, presents to the ED with new‐onset, severe lumbar pain. When you enter the room to examine Mrs. R., she is tearful, grimacing and reporting severe pain. She asks you for immediate pain relief. Her husband appears scared and begs you to help his wife. You respond that you need to know more about the pain before you can help her and receive the following pain report.

Mrs. R. characterizes the pain as a constant aching, centered at her lower back and non‐radiating. She reports no weakness, numbness, tingling or burning sensations or difficulties with control of urinating or defecating. Mrs. R. slipped on the ice while walking her dog 12 hours ago. Mrs. R. reports she was able to get up and return home with moderately severe pain, which she rated as an intensity of 7 out of 10. She took 400 mg ibuprofen and retired to bed. Mrs. R. woke up early this morning with severe low back pain, which she rates as an intensity of 9 out of 10. Her pain is not better in a seated or prone position instead of standing. However, the pain is made slightly worse by spine flexion. Mrs. R. acknowledges intermittent episodes of aching low back pain for the

last year which she rated as an intensity of 3 out of 10. She has had minor lower back aches in the past and attributed them to getting older and overdoing. She reports no allergies but explains that previous use of post‐operative morphine resulted in severe itching. You place an order for pain meds.

Now that Mrs. R. has obtained pain relief, she is able to report the details of her medical history.

Mrs. R. was treated for breast cancer in 2004. She received a left breast lumpectomy and radiation. Since her cancer was hormone‐receptor positive, Mrs. R. received a follow‐up five‐year treatment with anastrozole, an aromatase inhibitor. Aromatase inhibitors (AI) prevent the conversion of androstenedione to estrogen by aromatase in post‐menopausal women. Mrs. R. entered menopause at age 46, earlier than the average 51 years. She was concurrently treated with an oral bisphosphonate, alendronate (Fosamax), to prevent bone loss during AI treatment. Mrs. R. admits that she was not always compliant with her bisphosphonate treatment. Mrs. R.’s last bone density

test in 2008 has a T‐score of ‐1.6 which her primary care physician told her is OK, although her bone density is below normal. Other medical history includes treatment for severe asthma using oral corticosteroids during her late childhood and adolescence.

Mrs. R. achieved a 5‐year cancer free milestone last year. However, Mrs. R. and her husband are fearful that the severe back pain she is experiencing is due to a metastasis. Mrs. R. reports that her cancer diagnosis improved her overall health due to changes in her diet and exercise practices. She has been able to reduce her weight to 135 pounds, corresponding to a BMI of 23. She adopted a dog and walks a mile twice daily. Although elevated before her diagnosis, her cholesterol and blood pressure are now in the normal range without medication. Her diet includes foods rich in calcium but she avoids most dairy products. She has also given up social drinking. She has faithfully used her calcium and 1000 IU vitamin D supplements. Mrs. R. states that she never smoked due to her asthma. Mrs. R. is married to her husband of 35 years and has three adult children aged 33, 32 and 30.

Considerations:

- What pain analgesia did you prescribe based on Mrs. R.’s pain report?

- Based on Mrs. R.’s report of focal lumbar pain, what do you think is the likely diagnosis, name two other possibilities?

Spinal imaging shows a vertebral compression fracture at L4. Mrs. R. and her husband are relieved to learn the news since they feared a metastasis. Mrs. R. states that she doesn’t understand how this could happen because she has felt so well in the past year. You explain that Mrs. R. has many risk factors for development of osteoporotic fractures including early menopause, use of an aromatase inhibitor, and a history of corticosteroid use. The use of an AI, in addition to noncompliance with the bisphosphonate was likely to have been very significant.

- What are the risk factors that predisposed Mrs. R. to the development of this osteoporotic fracture?

Conservative management of Mrs. R.’s vertebral compression fracture and osteoporosis will include both non-pharmacological and pharmacological approaches. Physical therapy provides instruction about how to avoid postures that cause pain during mobility and activities of daily living. Promoting good posture and body mechanics reduces compressive loads on the spinal injury and speeds healing. An exercise program to build core strength is included in addition to weight-bearing and aerobic activity. Bracing can be used to facilitate maintenance of appropriate posture during the healing process. Vertebral augmentation using either vertebroplasty or khyoplasty (see definitions below) may be used if conservative management fails in order to avoid surgery.

Mrs. R. will be discharged and has agreed to set up an appointment with her primary care physician who will coordinate her treatment. You have recommended that Mrs. R. take 400 mg ibuprofen every 6 hours for the next two days to help with inflammation and pain. An oral opioid will be prescribed for acute management of Mrs. R.’s pain. She’ll also need constipation prophylaxsis.

- You have decided to prescribe oxycodone to Mrs. R. on discharge. What dosing schedule will you start with? What dosing schedule would you propose, if the pain is expected to last for 3 weeks?

- If Mrs. R. was a 75-year old woman who had recently been diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment and disrupted sleep, which of the following side effects of opioids would you spend the most time discussing at discharge?

- Respiratory depression

- Drowsiness

- Nausea

- Constipation

Case 2: New‐Onset Severe Upper Abdominal Pain

Mr. M., a 25‐year old graduate student, presents to the ED with upper abdominal pain on January 2, 2010. He awoke four hours ago with persistent drilling pain, which he rates as an intensity of 8 out of 10. The pain is centered in his upper abdomen but radiates to his back. In addition, he complains of concomitant nausea, vomiting, abdominal tenderness and fever. When you entered the room, Mr. M. was curled up in the fetal position on his left side. He reports that the pain is made worse by lying down on his back and relieved by bending forwards. He does not believe his current symptoms are related to his past treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Mr. M. tried taking Tums, cimetidine (Tagamet HB) and acetaminophen on awaking in pain but vomited the contents of his stomach. Mr. M. appears dehydrated and when asked states that he is very thirsty and has not urinated since awakening.

Mr. M. was treated for GERD last year using omeprazole (Prilosec) and has been symptom‐free for five months. In addition, Mr. M. was advised to eliminate or curtail his alcohol use, improve his diet by reducing fried foods and to lose weight. His physician told him these measures would also reduce his triglycerides and cholesterol, which were borderline high. When questioned about his diet in the past 48 hours, Mr. M. states that his last meal was a fried food at the New Year’s Eve party around 11 pm. Mr. M. began consuming alcoholic beverages around 7 pm on New Year’s Eve and drank alcohol for the next 12 hours. He doesn’t know how many drinks he had, but guesses at least 15. Mr. M. slept until 6 pm on New Year’s Day when he got up to drink water and urinate. He tried to eat crackers but was too nauseous. He retired to bed and awoke at 3 am today with his current symptoms.

Mr. M. is febrile, temperature of 38.1 C, and has a rapid pulse, 100 beats per minute. You examine Mr. M. and confirm the location of pain and the presence of abdominal tenderness. You note that Mr. M. is overweight (height 5 ft 11 in, 205 pounds, BMI 28.6 kg/m2) and ask about his weight and dietary history. He reports that he gained 15 pounds after leaving college at age of 23. He is bartending and going to graduate school and has less time to exercise. He admits to a history of 5 years of very heavy drinking in college although he only drinks moderately now. He concedes that although he modified his diet while having GERD symptoms, he tends to eat fast food. You order a complete blood count (CBC), liver function tests (LFT) and lipase level and abdominal

ultrasonography (white count for evidence of infection; hematocrit allows monitoring of

rehydration; LFT give indication of gallstone disease; lipase level indicates pancreatic inflammation; ultrasonography visualization of gallstones).

| Pain Characteristics | Other Symptoms and Signs | Risk Factors | |

| GERD |

Burning pain which seems to radiate from stomach to throat Chest pressure or pain Chest pressure relieved by burping |

Acid reflux Belching Difficulty swallowing Dry cough Hoarseness of sore throat |

Obesity Hiatal hernia Pregnancy Smoking Dry mouth |

| Acute Gastritis |

Gnawing or burning stomach ache or pain May be made better or worse with eating |

Nausea Vomiting Belching or bloating Loss of appetite |

H. pylori infection Regular use NSAIDS Exceessive alcohol use |

| Acute Cholecystitis (usually due to gallstones) |

Severe episodic pain in upper right part of abdomen Quality may be aching or sharp and stabbing Pain intensified when drawing breath Pain radiation from abdomen to back between shoulder blades or right shoulder Abdominal tenderness Movement does not make pain worse Intensity of pain makes finding comfortable position difficult Pain usually occurs after mean, especially a large meal or one high in fat, at night |

Nausea Vomiting Loss of appetite Fever Chills Abdominal bleeding |

For gallstone formation: Female sex Older age Obesity High-fat diet High-cholesterol diet Pregnancy Diabetes |

| Acute Pancreatitis |

Onset may be gradual or sudden Tolerable to severe upper abdominal pain Quality may be aching or sharp and stabbing or boring Pain radiation to back, flank, chest or lower abdomen Abdominal tenderness Eating makes pain worse Pain made better by sitting or leaning forward instead of lying on back |

Nausea Vomiting Fever Rapid pulse Dehydration |

Gallstone, which may obstruct common bile duct Heavy alcohol use |

Considerations:

- Which diagnosis is most likely based on Mr. D’s pain report and associated symptoms? Refer to table of possible diagnoses of upper abdominal pain.

- GERD

- Inflammation of stomach lining – gastritis

- Inflammation of gallbladder – cholecystitis

- Inflammation of pancreas – pancreatitis

- You prescribe intravenous fluids for rehydration and intravenous morphine for pain relief. Which of the following side effects of morphine will require concurrent management?

- Constipation

- Nausea

- Dizziness and drowsiness

- Both constipation and nausea

Case 3: Sickle Cell Vaso-Occulsive Crisis Pain

Mr. B. is a 20-year old African-American male pre-med college student with a diagnosis of sickle cell disease (SCD), Hb genotype SS. He presents to his local ED with intense lower back pain, described as gnawing. Mr. B. reports that the pain radiates to his hips and down to the backs of his knees. He needed support ambulating into the triage area. Mr. B. states this is his worst crisis pain ever and rates the pain intensity as 8 out of 10. Mr. B. says that the pain was 3/10 at the beginning of the crisis and has steadily intensified. Since the pain started about 36 hours previous, oral pain medications have included acetaminophen, ibuprofen and dihydrocodeine. Mr. B. reports that he has run out of dihydrocodeine and has no more refills.

The patient specifically requests PCA containing morphine. When questioned about this, he says that during his last crisis, he rapidly achieved relief.

For the past two years, Mr. B. has averaged about 6 vaso-occlusive crises each year, none requiring hospitalization until 3 months ago. The patient's last crisis was 3 months ago, only a few days after his 20th birthday. That crisis had a maximum pain intensity score of 7 out of 10, and was his most severe until today. Pain was greatest in hips and thighs. He was hospitalized and received intravenous morphine using a PCA-pump. Pain resolved and patient was released after 36 hours with a dihydrocodeine prescription.

The day before current pain crisis, patient attended an outdoor concert and consumed alcohol to celebrate the end of exams. He reports becoming slightly dehydrated. Patient denies smoking tobacco or cannabis or other illicit drug use. He is currently planning to return to his home state for a summer internship position.

Normal medications include 1 mg folic acid per day (hemolysis treatment) and hydroxyurea (increases hemoglobin F). Mild crisis pain is relieved with 400 mg ibuprofen and 650 mg acetaminophen every 6 hours. Mild to moderate crisis pain is relieved by adding 30 mg dihydrocodeine every 4 hours.

Patient’s primary care physician, who is located out of state, has not examined patient since the last crisis. Baseline test results for comparison include: Hb 10.0 g/dl, Reticulocytes 7.5%, WBC 10 x 109 l-1.

Current vital signs: Temp: 38.0°C, HR: 85 beats per minute, RR: 20 breaths per minute; BP 125/85 mm Hg, and SpO2 92%. Mr. B.’s urine test was negative for hematuria and bacteria, but positive for cannabinoids. The color of his urine is dark yellow. His bloodwork results include: Hb 9.0 g/dl, reticulocytes 10.5%, and WBC 12 x 109 l-1. Auscultation results were unremarkable with normal bowel sounds. Abdomen was nontender without evidence of organomegaly. Lower back and hips were tender to palpation.

Considerations:

- Which of the following treatments is not recommended to resolve the pain associated with the present crisis?

- Administration of IV fluids

- Administration of oxygen to achieve saturation

- Administration of IV morphine

- Nonpharmacological approaches including distraction, guided imagery, massage and heat

- None of the above

- Which of the following is not recommended as adjuvant therapy during this crisis?

- Gabapentin

- Stool softener and or laxative

- Acetaminophen and or ibuprofen

- Antiemetic

- Antihistamine

- During self-treatment for recent pain crises, the patient reported that in order to achieve any significant decrease in pain he needed to double the codeine dosage, in addition to using acetaminophen and ibuprofen. This self report most likely indicates:

- Tolerance

- Physical dependence

- Pseudoaddiction

- Patient is having vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs) with more severe pain than in the past

- Diversion

- Patient asks for your opinion concerning the relative ineffectiveness of oral codeine versus intravenous morphine for his pain relief. What is your response?

- Intravenous analgesia is superior to oral analgesic

- Most patients have psychogenic belief in superiority of intravenous morphine

- Patient use of cannabinoids attenuated the analgesic effect of codeine

- Patient may have genotype for poor metabolizer of codeine

- The minimal efficacy of codeine compared to morphine limits its use even for self-treatment

Answers

Case 1

Question 1

Answer: hydromorphone is suitable for severe pain, has quick onset given either by mouth or i.v. and has less frequency of side effects than morphine, including itching; hydrocodone is a combination schedule III drug for oral use, generally for moderate pain; codeine is not metabolized in patients without CYP2D and has oral, I.M. or SubQ dosing; tramadol is dosed orally, prescribed for moderate pain and has a mixed mode of analgesic action.

Question 2

Answer: Mrs. R. reports pain with a lumbar spine focus, an unremitting timing and dull quality. In addition she reports no radiation of pain, absence of radicular pain, numbness or tingling and no motor symptoms. Whereas, a metastasis, fracture or infection could reasonably result in focal pain, a compression of the nerve root or spinal cord is likely to result in some neurological and/or non-localized pain component.

Question 3

Answer: bone density, measured using a dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan, is important and Mrs. R. had a below average bone density during her last test two years ago; osteoporotic bone thinning is a painless process until a fracture occurs, therefore a patient can feel fine and still develop osteoporosis ; upper-body strengthening exercises promote strong bones and slow bone loss primarily in the arms and upper spine; there are many excellent sources of dietary calcium in the absence of dairy including green leafy vegetables such as mustard greens and kale, canned salmon with bones, almonds and soy products. Recommendations for vitamin D supplementation range up to 1000 IU daily for those over 50 years of age.

Question 4

Answer: the fracture causing the pain will take time to heal and the attendant pain may be expected to last for several days or weeks. Following an initial treatment with short-acting opioid agonist, time-specific dosing of controlled-release oxycodone may establish consistent analgesia which will encourage mobility and reduce the sense of the pain controlling the patient; the availability of breakthrough medication should be made available in the event of severe, uncontrolled pain; frequent dosing required when using scheduled Percocet or immediate-release oxycodone keeps the patient more focused on the pain; avoid combination of oxycodone with ibuprofen if you have instructed patient to take ibuprofen independently, be aware that the maximum daily dosage of ibuprofen is 1200 mg.

Question 5

Answer a and b: the combination of disrupted sleep and drowsiness caused by beginning an opioid regimen, places an elderly patient at increased risk for falls; her underlying osteoporosis will mean that any fall will be more likely to result in additional fractures. The risk of respiratory suppression increases in patients with underlying respiratory compromise. It is important to assess whether sleep difficulties include sleep apnea.

CASE 2

Question 1

Answer: d, pancreatitis based on pain report including central upper abdominal location, drilling or boring quality, severity, acute onset, made worse by lying on back and associated vomiting and nausea

Question 2

Answer: d, constipation is the most prevalent side effect, so a stool softener and plenty of fluids are always advisable, but nausea is a pre-existing condition which may be exacerbated by the morphine so it requires treatment also so that patient can resume ingesting liquids orally; dizziness and drowsiness and the most likely side effects to diminish with use.

CASE 3

Question 1

Answer: e. all of the treatments are recommended; patient reports becoming dehydrated previous day and has dark yellow urine; patient has suboptimal blood oxygenation; patient has severe pain which was previously controlled using morphine.

Question 2

Answer: a. gabapentin is as neuromodulator and patient does not report any neuropathic pain.

Question 3

Answer: d. this patient has historically self-treated for VOC-induced pain and is presenting to ED for uncontrolled pain; patient reports that the pain of recent VOCs has greatly increased.

Question 4

Answer: d. patient received morphine for the first time during last crisis and noted immediate effectiveness; an estimated 6% of African Americans have genotype for poor metabolizers limiting the effectiveness of this patient’s pain self-management plan, especially if the pain of VOCs is intensifying over time.

Chronic Pain: Clinical Correlation

Instructors can use this section to build out a patient-specific clinical correlation.

Our Patient

This section should include a presentation of a patient with acute pain. There should be a relevant link to the anatomy section which follows.

Chronic Pain Characteristics

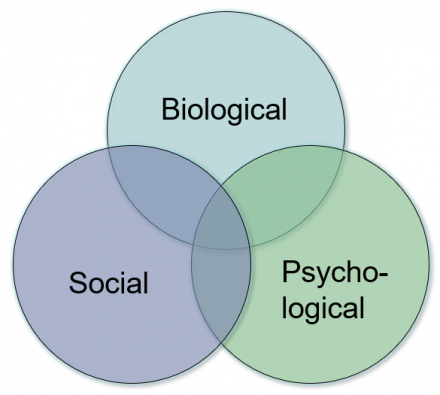

Biopsychosocial Origins of Pain

This section should include information about the biopsychosocial system that centers around the patient with pain. Reference should be made to the case presented.

Generalized Biopsychosocial Model

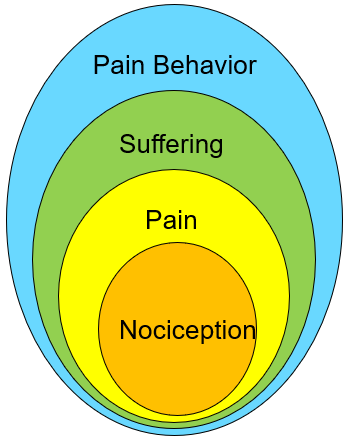

Pain Specific ‘Biopsychosocial’ Model (Loeser Model)

Interpretation: a specific nociceptive event may result in a range of responses including: pain, suffering and pain behavior, depending on the context in which nociception occurs.

Application of the Biopsychosocial Model in Pain Care

The biopsychosocial model is used in develop more effective plans for pain care with goals that include:

- Decreased pain

- Increased physical activity

- Improved sleep

- Lower stress levels

- Patient specific personal goals

Pain Treatment Plan Elements

This section should include information about pain treatment plan elements. Reference should be made to the case presented.

Pain Treatment Plans

4 components

- Goals for treatment

- Expectations

- Treatment modalities

- Time Course

1. Goals for treatment

S.M.A.R.T. I

- Specific

- Measurable

- Attainable

- Relevant

- Timely

S.M.A.R.T. II

- Specific

- Mutually agreeable

- Adaptable

- Realistic

- Time-bound

Patient + Provider = Success

2. Expectations for Treatment

Expectations for treatment vary depending on:

- Type of Pain

- Setting and context

- Patient needs

Expectations should be outlined explicitly and include the patient:

- Check for understanding

- Ensure shared-decision making

- Balancing pain relief and side effects

3. Treatment Modalities

Pharmacological

- NSAIDS and acetaminophen (OTC analgesics)

- Neuromodulating agents

- Anti-depressants

- Anti-convulsants

- Local anesthetics

- Others

- Opioids

- Non-pharmacological

- Psychological

- Manual (PT, massage)

- Activating (occupational)

- Complimentary and alternative

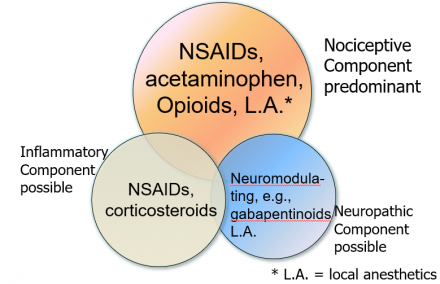

Mechanism-Based Classification of Pain

- Generally straight-forward to understand and apply

- Enhances understanding of relevant disease mechanisms

- Guides the choice of pharmacological treatments

- Determines the extent and type of non-pharmacological treatments

- Anticipates the time course and degree of disability associated with pain

Mechanism-Based Classification of Pain: Management of Acute Pain

4. Time Course

- Reflects realities of underlying disease:

- Make sure to supply analgesia for the anticipated duration of acute pain: once analgesia wears off, your patient may have a sharp increase in pain!

- Influenced by individual factors

- Personal history of pain, other conditions, psychological and social state

- Includes a plan for re-assessment

- Don’t assume therapy is effective, check for pain relief

- Treatment end

- If opioids are prescribed for more than 3 days, make sure to structure a sound tapering plan to avoid withdrawal symptoms

Recognizing Acute Pain in Patients with Chronic Pain

This section should include information about assessment of pain. Reference should be made to the case presented.

Questions for Review

- What distinguishes neuropathic pain from nociceptive and inflammatory pain?

- What features of a patient’s description of pain can tip you off to a neuropathic pain element?

- Where is the pain generator or generators for this patient?

- How effective was the first treatment for this patient?

- What steps would you take to further optimize this patient’s pain management?

- Are there medications or treatments that you would not use in this patient?

Additional Study Material

Pain Pharmacology III – Opioids Self-Study

- What are some specific medical conditions, associated with pain, for which opioids may be used chronically (name 3)?

- What is the difference between addiction and physical dependence? Does morphine induce physical dependence? How is the role of morphine in physical dependence different from that in addiction?

- Can you stop opioids suddenly? If you do suddenly stop or sharply decrease the opioids given to a patient, what will happen? What physical manifestations will this produce?

- Would you ever use a DEA Schedule 1 drug in your clinical practice?

- Is there ever a reason to combine two opioids?

- What are the mechanisms of action of tramadol? Is this drug DEA scheduled?

- Name 5 Schedule II opioid agonists? How do these differ (list three important differences)? Do all of these agents act at the same receptor(s)?

- What is the number of deaths from opioid prescription pain medicines, according to the latest numbers?

- How many prescriptions are filled each year for the 3 most common opioid agonists, according to the latest numbers?

- What is the percentage of people for whom codeine is not an effective analgesic? Why does this happen? What will you say/do when someone tells you that codeine doesn't work for them?

- How likely are you to prescribe methadone for routine post-operative pain? What are the risks associated with the use of methadone for chronic pain?

- How likely are you to prescribe oxycodone for routine post-operative pain? What is the abuse potential for oxycodone?

- What should you do to prevent or treat opioid-induced constipation? Is it better to prevent this side effect or anticipate it and treat it in advance? What do we call severe constipation (one word)? Have people died from opioid-induced constipation? What is the percentage of people who experience opioid-induced constipation on a standing dose of opioid medication?

- What is the major cause of death in people who take too much opioid? How would you identify the patients who might be at risk for this adverse event?

- How will you identify those patients at risk for opioid abuse? How can you monitor patients who might be at risk?

- Besides constipation, respiratory suppression, and dependence, what are the other common side effects of opioid agonists? Are all opioids the same in this respect?