Background

- Dementia and pain are both highly prevalent conditions in older adults

- An estimated 50% of older adults with dementia experience pain on a regular basis, similar to cognitively intact older adults

- Pain prevalence is not affected by dementia subtype

- Pain impacts social interactions, appetite, sleep, mood, behaviors, quality of life

- Communication becomes increasingly impaired as dementia progresses, putting those with dementia at especially high risk of experiencing unrecognized and under-treated pain

Presentation of Pain in Dementia

- Highly variable presentation depending on type and severity of dementia, thus making detection and assessment challenging

- Those with mild to moderate dementia may have intact ability to communicate about painful conditions

- Those with moderate dementia may not be able to recall or provide details about painful episodes

- Those with severe dementia who are more nonverbal may present atypically with behavioral changes

Challenges in Pain Assessment: Mild to Moderate Dementia

- If patients are unable to provide reliable history, other aspects of the pain assessment become especially important:

- Caregiver report

- Physical exam, particularly during observed movement (for example, a patient who always says they’re fine while sitting, but hasn’t been walking at home because of foot pain)

- In addition to meticulous attention to caregiver report and a thorough physical exam, the American Geriatrics Society has identified six areas of common “pain behaviors” for cognitively impaired older adults:

- Facial expressions

- Verbalizations or vocalizations

- Body movements

- Changes in interpersonal interactions

- Changes in activity patterns or routines

- Mental status changes

- Many of the above pain behaviors are nonspecific and can be seen with other types of distress in those with dementia

Biological/Sensory Dimension of Pain and Dementia

- Dementia does not appear to influence pain threshold, tolerance or habituation (becoming accustomed to pain)

- Heart rate and blood pressure changes in response to pain may be blunted with decreasing cognitive function

Psychosocial Dimension of Pain and Dementia

Affective

- Often subsumed under category of neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) including delusions, hallucinations, agitation/aggression, depression/dysphoria, anxiety, elation/euphoria, apathy, disinhibitions, irritability/lability, and aberrant motor, night-time, and/or eating behaviors

- Pain may trigger or reduce these symptoms

- Sedative effects of pain treatment may mask behaviors whereas treatment may also improve behaviors, depending on their etiology

- Summary: While NPS are not a specific sign of pain, pain may manifest as NPS. There is little evidence that the affective domain of pain is significantly altered in those with dementia

Cognitive

- Understanding pain, our beliefs and thoughts about it and the decisions we make about our symptoms including coping attempts, treatment seeking and acceptance.

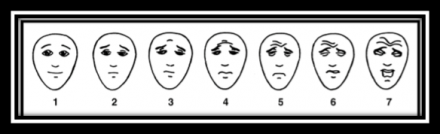

- Dementia is associated with impaired semantic memory of pain including difficulties using pain descriptors and differentiating painful from nonpainful situations (use caution with facial scales)

An Approach to Assessing Pain in Dementia

- Given the unique challenges of detecting and assessing pain in the person with dementia, a comprehensive approach is needed.

- Critical components of the assessment include:

- History

- Self-report is the gold standard, if patients are able to provide it

- [Clinical Pearl] older adults may not always identify with “pain” as a descriptor. Ask about discomfort, aching, heaviness, burning, etc.

- Caregiver report is essential if patients have impaired communication

- [Clinical Pearl] focus the interview on the functional and behavioral impact of suspected pain

- Self-report is the gold standard, if patients are able to provide it

- Physical exam, with special attention to:

- Oral/dental exam

- Musculoskeletal exam for bruises or occult fractures

- Abdominal exam for urinary retention or constipation

- Full skin exam for skin tears, ulcers, or other painful skin conditions

- Observed movements (including weight-bearing when possible)

- Routine use of a professionally developed behavioral assessment tool is recommended along with a comprehensive history and physical exam for more valid pain assessment

- History

Practical Tips on How to Communicate with a Person with Dementia

- Eye Contact

- Look directly at the other person when speaking or listening

- Move eyes spontaneously and naturally

- Body Position

- Sit or stand directly in front of the person. Be sure you have his or her attention before speaking

- Place yourself on the same level with the other person as much as possible. Do not stand over someone who is sitting or lying

- Position yourself close enough to be seen and heard clearly, usually about three to six feet away.

- Face and head movements

- Have a calm expression. Express changes on face appropriately

- Nod appropriately and positively. Avoid a deadpan expression.

- Hand and arm movements

- Use hand movements for emphasis

- Use gentle touch to get or focus attention

- Speech rate and tone

- Speak slowly

- Form and say words carefully

- Use short sentences

- Ask one question at a time. Wait for an answer before asking another question

- Be patient

Adapted from L. Teri, 2012

Assessment Tools for Pain in Dementia

- Multiple self-report tools and over 35 observational tools are available, although there is no gold standard.

- No single tool can be applied to all care settings and all severities of dementia.

- We will review a few tools that are more commonly used in clinical practice

Benefits of Using Assessment Tools

- Attempts to provide an objective measure of a subjective experience

- Results can be used to track an individual’s pain levels across time or after treatments

- Nurses have reported tools to be beneficial, especially for standardized reporting of pain levels to the care team and for helping less experienced staff recognize pain in dementia

Challenges of Using Assessment Tools

- No gold standard

- Insufficient evidence regarding clinical utility and validity across different care settings

- Since many tools are based on behavioral symptoms, they may detect distress, not just pain

Self-Report Tools

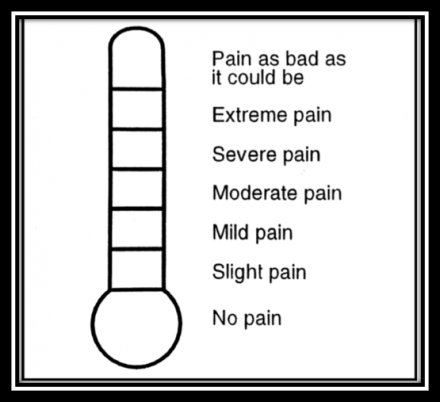

Face scales and visual descriptor scale have been studied in older adults

[Clinical Pearl] vertical, rather than horizontal tools, may be easier for older adults to use

Challenges to Understand and Overcome

Challenges

- Patient factor

- Impaired memory of painful episodes

- Provider factor

- Assumes that since patient says they have no pain right now, s/he is not suffering from pain

- System factor

- Care providers may not be familiar with patients in acute care settings

Solutions

- Patient factor

- Reliance on caregiver report

- Provider factor

- Movement-based assessments

- System factor

- Use of assessment tools to provide objective measurement of pain levels from shift to shift

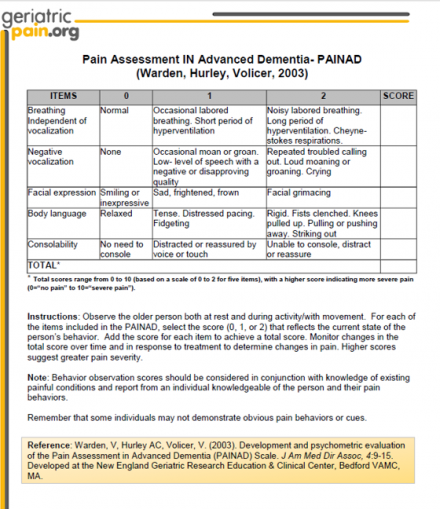

Observational Tool: PAINAD

- PAINAD = Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia

- Key features:

- Target population: advanced dementia

- Tested in acute care, long-term and community settings

- Requires a 2-5 minute observation period (of patient both at rest and during activity) prior to completing the scale

- Score interpretation: 0 (no pain) to 10 (severe pain)

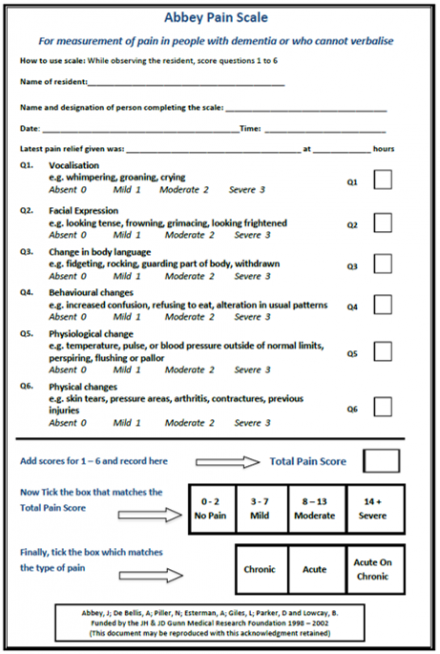

Observational Tool: Abbey

- Key features:

- Target population: late-stage dementia

- Tested in long-term care settings

- A movement-based assessment

- Intended for frequent, serial assessments (e.g. before and after treatment)

- Score interpretation: 0-2 no pain, 3-7 mild, 8-13 moderate, 14+ severe

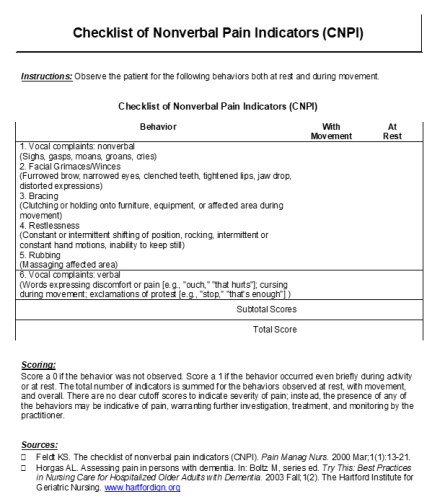

Observational Tool: CNPI

- CNPI = checklist of nonverbal pain indicators

- Key features:

- Target population: nonverbal severe cognitive impairment

- Tested in acute care, long-term care and community settings

- Compares patient behaviors at rest and at movement

- Score interpretation: 1-2 mild, 3-4 moderate, 5-6 severe pain

Teaching Points

Specific Behaviors

Practice identifying specific behaviors that may be indicative of the presence of pain.

What do you see when you observe this patient? What are some potential indices of pain?

The video shows restlessness with constant shifting of position, grimacing, clenched teeth, narrowed or shut eyes, furrowed brow, changes in pattern of breathing. Any of these may indicate pain.

How To Communicate With A Person With Dementia

How do you communicate with a person with dementia in order to obtain a proper pain assessment?

Observe how this healthcare worker interacted and asked questions of the patient. What might you do differently?

The healthcare worker has a very calm quiet voice that might help soothe the patient and uses gentle touch to get patient’s attention. However, questions were asked in a rapid fire and slowing down would have given the patient a chance to answer. It would have been better to stand a bit lower on the bedside to face the patient.

Pain Assessment With Activity

How can you assess pain with activity?

What can you observe in this video that might suggest pain behavior after the head of the bed is elevated?

A thorough assessment and certain behavioral assessment tools (e.g., CNPI) include observations and questions at rest and with activity. While this patient exhibited no pain behaviors at rest when the head of the bed was elevated the patient’s jaw dropped and upper body became tense. On closer inspection note the silent delayed eye tearing and saddened face.

Hear from the Family/Caregiver

Recognizing and Managing Pain in People with Dementia.

Please watch this video from Veterans Admin - Recognizing and Managing Pain in People with Dementia.

Key Summary Points

- Pain is under-reported and under-treated in the persons with dementia

- A thorough physical exam and history (including collateral information) are essential to assessing pain in dementia

- pain may not always be obvious: use extra time to examine oral cavity, skin, abdomen, movement

- People with dementia often have impaired ability to self-report pain, thus necessitating fuller scope assessment including use of validated behavioral pain assessments tools and information from caregivers

- Many tools are available, but none are perfect. Six areas of common “pain behaviors” for cognitively impaired older adults include:

- Facial expressions

- Verbalizations or vocalizations

- Body movements

- Changes in interpersonal interactions

- Changes in activity patterns or routines

- Mental status changes

- Behavioral changes can be a manifestation of pain in dementia. If a person develops behavioral changes, look for the underlying cause and keep pain on the differential as a potential cause