Nociceptive Pathways and the Impact of Dementia

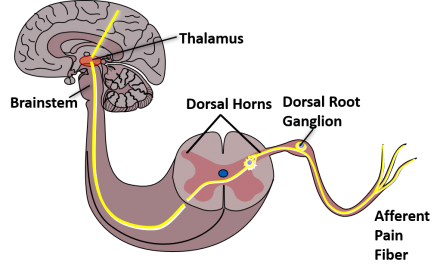

Before developing a treatment plan for Mildred, let’s first look at how the body processes pain. Somatic pain associated with knee osteoarthritis is transmitted through nociceptive pathways. The pathway includes transduction (initiation of a nociceptive impulse), conduction (transmission of the impulse down a peripheral nerve), transmission (movement of the action potential from the peripheral to central nervous system), perception (the impulse moves from the dorsal horn of the spinal cord to the brain where it is interpreted), and descending modulation (integrated impulse is modulated via descending fibers down the spinal cord to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord). As we discuss each of these four processes, we will consider the impact of dementia on pain processing.

Nociceptive Pathways and the Impact of Dementia: Transduction

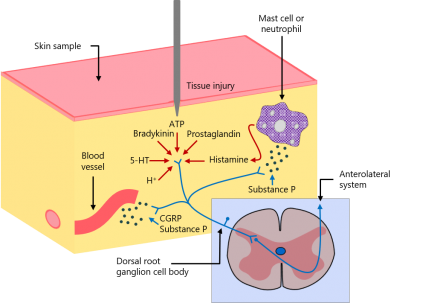

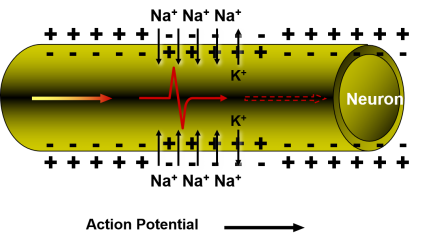

In knee osteoarthritis, inflammation in and surrounding the joint stimulates peripheral nociceptors in and around the synovium, bone, muscles, and tendons. Receptor stimulation triggers an influx of cations which ultimately lead to nerve cell depolarization and generation of an action potential termed transduction. Evidence has not demonstrated that this process is altered in someone with dementia.

Nociceptive Pathways and the Impact of Dementia: Conduction

After the nociceptive impulse is initiated via transduction it travels down the peripheral nerve into the central nervous system. The propagation of this impulse down the peripheral nerve is termed conduction and has not been demonstrated to be altered in someone with dementia.

Nociceptive Pathways and the Impact of Dementia: Transmission

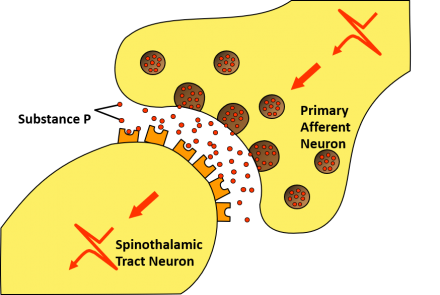

The nociceptive impulse travels into the central nervous system via the primary afferent neuron. From there, the impulse is transmitted through exocytosis mediated pathways to the efferent spinothalamic track neuron in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Evidence does not suggest that transmission is altered in persons with dementia compared to cognitively intact individuals.

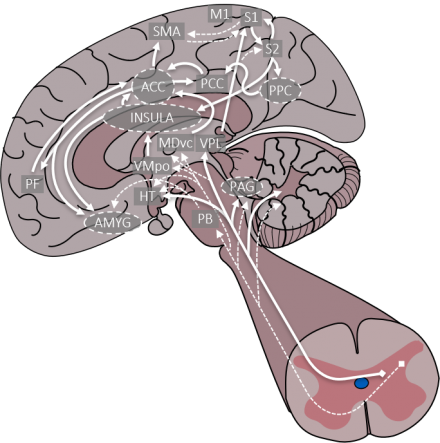

Nociceptive Pathways and the Impact of Dementia: Perception

The nociceptive impulse then travels from the spinal cord to the brain where it is integrated throughout via pathways depicted. The pain experience can be influenced by changes in the cortical and subcortical areas of the brain as a result of dementia-related neurodegeneration. This results in alteration of the interpretation of the input to the individual. Moreover, the phenomenon of central sensitization in which nociceptive inputs such as those from osteoarthritis can trigger central nociceptive pathways resulting in pain hypersensitivity.

Nociceptive Pathways and the Impact of Dementia: Modulation

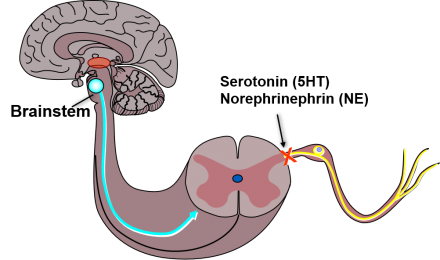

After the nociceptive impulse is integrated within the brain, descending fibers travel back down the spinal cord and modulate the pain response. Given the necessary cognitive processing to facilitate modulation, this process can also be impacted by dementia. In fact, one study found persons with dementia experience less anticipated benefit from analgesics potentially diminishing their overall effectiveness in this population.

Management of Knee Pain in Persons with Dementia

Our history and physical exam corroborate that Mildred has knee osteoarthritis. The resultant pain from her knee arthritis is interfering with her physical, psychological, and social functioning. The cornerstone of pain management is to improve Mildred’s functioning which may or may not decrease her pain intensity.

Stepped Approach to Persistent Pain

Health care providers use a stepped approach to treating persistent pain taking into account both non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic approaches as concomitant treatment plans improve outcomes better than either one by itself. Regardless of the specific interventions chosen, patients should be advised of the importance of staying active and actively participating in their care.

Adjunctive Approaches

- Acupuncture

- Duloxetine

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

- Glucosamine sulfate

Adjuvant approaches should be considered at each step in the pathway. Additional considerations for the management of knee pain from osteoarthritis include: acupuncture, duloxetine, cognitive behavioral therapy, and glucosamine.

Acupuncture compared to SHAM reduces pain and improves function in patients with persistent knee osteoarthritis pain.

Duloxetine is FDA-approved to manage persistent musculoskeletal pain due to osteoarthritis; and its mechanism of action may be related to a reduction in central sensitization. Adverse reactions include nausea, dry mouth, dizziness, hepatitis and liver failure, suicidal thoughts, and abnormal bleeding—especially when taken with NSAIDs or anticoagulation drugs.

Cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT, includes a wide range of approaches designed to reduce the negative impact of pain on daily life, improve physical and emotional functioning, increase effective coping skills, and reduce pain. CBT can often be a helpful adjunctive therapy in patients with chronic pain. While there are inadequate high quality data to support the efficacy of CBT for patients with dementia, our clinical experience highlights the usefulness of simple cognitive behavioral techniques such as distraction and relaxation, even in patients with mild to moderate dementia. For such individuals, involving caregivers in CBT sessions to help facilitate compliance with home practice and to help their own caregiver stress may be useful. Glucosamine is available in several forms, with only the glucosamine sulfate preparation exhibiting clinical effectiveness. Compared to placebo, glucosamine sulfate significantly reduces pain and increases physical function without additional adverse effects.

Step 1

Non-pharmacological approaches.

Step one is what should be considered for all patients: education about persistent pain including a self-management program, encouraging participation in exercise and physical activity, weight control programs for people with arthritis and knee pain who are overweight, and instructions in the use of heat or cold modalities (such as hot packs, thermal wraps, ice packs, etc.). Adjunct treatments that have potential to redistribute loads across the knee joint such as the use of assistive devices for ambulation, knee bracing, patellofemoral taping, and wedged shoe inserts might be helpful in some cases.

For some patients with arthritis and knee pain, and particularly those with dementia, a referral to a physical therapist can improve the probability of a safe and effective non-pharmacological treatment approach. The therapist can make recommendations and modifications to the treatment program tailored to the patient’s individual needs. The therapist can also include instruction to family members or care givers in these treatment approaches.

Non-Pharmacological Treatment Options: Exercise

- Aerobic Exercise

- Lower Extremity Strengthening

- Lower Extremity Joint Mobility and Muscle Flexibility

- Balance and Agility

Physical activity and exercise have been shown to help reduce knee pain and improve function for people with knee OA and is recommended in all evidence-based practice guidelines. Exercise programs typically will include aerobic exercise, and lower extremity strength and joint mobility components. For some patients, balance and agility exercises may also be beneficial.

Exercise: Aerobic Exercise

- Walking, cycling, swimming

- 30-60 minutes most days of the week

- 50 to 60% of heart rate reserve

Aerobic exercise includes activities such as walking, cycling, and swimming. They are submaximal exercises that are performed over an extended duration approximately 30-60 minutes. In addition to reducing knee pain and improving function, aerobic exercise can also be beneficial for improving cardiovascular fitness and assist in weight reduction. It is recommended that aerobic exercise be performed at an intensity equivalent to 50 to 60% of an individual’s heart rate reserve.

If patients have difficulty understanding this concept, then asking them to exercise at a level that increases their breathing rate and induces some sweating, yet still allows them to carry on a conversation while exercising can be a good rule of thumb to get close to this level of exercise intensity. The patient with dementia may need direct supervision by a family member or caregiver during exercise. Patients who are at a risk for falling may need to consider stationary cycling, swimming, or other aquatic exercise programs as a safer alternative.

Exercise: Lower Extremity Muscle Strengthening

Many patients with knee pain and arthritis have lower extremity muscle weakness so it would be beneficial to include exercises for these muscle groups in the exercise program. The program could include exercises for muscles of the hip and ankle as well as the knee, depending on the patient’s specific impairment profile. A physical therapist can help to determine which muscle groups may need strengthening. In addition, the therapist can assist in making any modifications to the exercises that may be needed to avoid harming the joints and setting appropriate limits for safe and effective strengthening. Strengthening exercises don’t always require expensive training equipment and the therapist can work with the patient and family to set up appropriate home program alternatives.

Exercise: Lower Extremity Joint Mobility and Stretching

Older adults with knee pain and arthritis often times have limited joint motion due to contractures in the joint capsules or from adaptive shortening of muscles associated with the lower extremity joints. If joint motion impairments exist, joint range of motion and stretching exercises can be beneficial. A physical therapist can assess patients for joint mobility impairments and provide them with an appropriate joint mobility program. In some instances, therapists may use manual therapy techniques to address joint motion impairments. During manual therapy techniques, therapists apply manual forces to the joint to target specific areas of the periarticular soft tissues that are believed to be limiting joint motion. These techniques can also be used to induce relaxation and reduce joint pain.

Exercise: Balance and Agility Exercise

It has been shown that some patients with knee pain and arthritis have difficulty with balance and coordination which could add to age-related risk for falling. These patients may benefit from balance and agility exercises and Tai Chi to address these deficits.

Non-Pharmacological Treatment Options: Assistive Devices

The displayed pictures represent commonly used assistive devices including a standard cane and a walker. A standard cane provides unilateral support and is generally used when one knee is predominately more affected than the other. It should be held in the hand opposite of the discomfort to unload weight from the affected joint. A walker provides the most stability and support bilaterally and includes pick-up and wheeled walkers.

Persons with cognitive impairment often have an easier time learning to use a wheeled walker. Importantly, as cognitive impairment advances to the moderate and severe range, persons with cognitive impairment may have difficulty learning to use an assist device or forget to use it altogether.

Non-Pharmacological Treatment Options: Devices to Address Knee Joint Loading

- Knee bracing

- Patellofemoral taping

- Shoe inserts

There are other devices available that are designed to address excessive loading of the knee joint that have been indicated in most evidence-based guidelines to have potential for providing benefit in reducing knee pain and improving function.

Knee braces are available that can provide stability to the knee and in some cases reduce loading on knee joints from excessive varus deformity. These braces do not work for all patients but perhaps can be considered for patients who complain of knee instability or exhibit varus malalignment.

Patellofemoral taping has been shown to be effective in reducing knee pain related to patellofemoral pain syndrome and may be helpful for some patients who have patellofemoral arthritis.

Finally, shoe inserts with built in wedges might be effective for reducing harmful loading and knee pain in some patients with knee osteoarthritis. Lateral wedged inserts are suggested by some for use in patients with varus knee malalignments to offset the potential for excessive adduction moments that could harm the medial knee compartment.

Conversely, medially wedged inserts are suggested for those patients with valgus malalignments to offset the potential for excessive abduction moments that could harm the medial compartment. In addition, non-wedged insoles that simply provide more cushioning to the shoe might help alleviate some discomfort from ground reaction forces.

Step 2

Topical preparations & acetaminophen.

The evidence supporting topical preparations for the treatment of knee arthritis is the strongest for topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs—commonly known as NSAIDs—which are available as a gel or patch. The best studied of these is diclofenac, or Voltaren. Available topical products are extremely safe, so these products should be seriously considered.

If capsaicin is prescribed, the patient must be educated about the transient burning sensation that may occur for about a week; the need to apply the medication multiple times a day—that is, three to four times a day; and the requirement to wash hands thoroughly following application. The transient increase in pain and safety precautions necessary when applying capsaicin often preclude its use in persons with dementia.

Over-the-counter methyl salicylate-containing products, such as Ben-Gay, are often used by patients to relieve persistent joint pain. These therapies induce a hot or cold sensation that helps mask pain. Such therapies are generally well-tolerated. But high quality evidence supporting their use is limited. Lidocaine patches are frequently used in clinical practice to help manage persistent pain. The patches have found to be very effective for the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy and post-herpetic neuralgia. But studies supporting their use for knee osteoarthritis is lacking.

Acetaminophen is extremely safe and efficacious when used appropriately. Many providers now use a more conservative maximum daily dose of 3 grams in 24 hours, because so many over-the-counter—for example, sleep aids and cold remedies—and prescription products—combination opioid and acetaminophen analgesics—contain acetaminophen. And, patients taking them simultaneously can accidentally overdose. A dose of 2 grams per day is recommended for patients with moderate liver disease; and caution should be exercised in patients with alcohol dependence or abuse.

Step 3

Minimally invasive treatment.

Local injections into the knee should be considered next. Corticosteroid injections into the knee joint space can be very effective at decreasing knee pain and increasing function in patients with knee arthritis. Injections are not offered more frequently than every 3 or 4 months and may lose efficacy over time. Risks associated with joint space injections include bleeding and infection. In general, it is safe to perform intra-articular injections in patients on anticoagulation as long as their level is therapeutic. Also, patients with diabetes should be counseled that their blood sugars may temporarily be elevated for several days after an injection.

Given the challenges of medication adherence in persons with dementia, corticosteroid injections are often extremely useful. Intra-articular hyaluronate can also be considered for select patients that continue to have uncontrollable knee pain despite steroid injections and an adequate trial of systemic oral analgesics including acetaminophen, NSAIDS and in appropriate patients, weak opioids. Usually, this therapy is reserved for patients with refractory knee pain despite the aforementioned therapies and are not going to consider knee replacement surgery.

Step 4

Systemic oral analgesics.

- Non-acetylated salicylates

- Weak opioids and tramadol

- Strong opioids

We previously discussed the role of acetaminophen which is a systemic oral analgesic included as part of Step 2, due to the evidence of its efficacy and favorable side effect profile. If patients do not achieve an adequate response to pain treatment with the first three steps, additional systemic oral analgesics are considered. When selecting oral analgesics, providers should consider the ability of someone with dementia to safely administer these therapies, often multiple times a day along as well as the drug-drug and drug-disease interactions.

Pain medications may or may not be required and when used should be viewed as a means to an end with the end being improved physical, psychological, and mental function. If analgesics are prescribed, this should be done using a stepped care approach as shown here, proceeding from that associated with the least potential for toxicity, for example, non-acetylated salicylates, to those with the most potential for toxicity, for example, strong opioids.

Non-Acetylated Salicylates

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications are not recommended for prolonged use, for example, in the patient with persistent pain, because of their potential for numerous adverse effects including gastrointestinal bleeding, renal insufficiency and failure, and precipitation or worsening of hypertension and congestive heart failure. Also, ibuprofen in particular should not be used in patients taking low dose aspirin for cardio protection or stroke prevention as it can lead to the aspirin being less effective due to a pharmacodynamic interaction. Non-acetylated salicylates such as salsalate and choline magnesium trisalicylate are less potent prostaglandin inhibitors than traditional NSAIDs and are considered safer. Sometimes patients who do not respond to acetaminophen will respond to these and should be considered.

Reference

American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015 Nov;63(11):2227-46. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26446832

Opioids

Opioids are effective analgesic, but are used with caution due to a number of deleterious side effects, misuse, abuse potential, and the threat of diversion.

Clinicians may consider opioids as an option in the context of moderate to severe pain refractory to other therapies contributing to functional impairment and poorer quality of life, and the therapeutic benefits outweigh potential harms. Therapeutic benefits include deceased pain and improved physical, psychological, and social function. Moreover, patients with dementia may experience a decrease in agitation and aggression when undertreated pain is better managed.

As with all medication, it is imperative that providers are familiar with appropriate dosing in older adults. In general, research and practice standards recommend opioid initiation at half the dose generally considered appropriate for younger patients. For example, in younger patient, a provider may elect to start hydrocodone 5 to 10mg formulated with varying doses of acetaminophen (for example, Norco or Vicodin), whereas in older adults the starting dose is 2.5 to 5mg of hydrocodone.

The common adverse effects of opioids include constipation which should be anticipated and prevented prophylactically with a bowel regiment, nausea and vomiting, dizziness, sweating, pruritus, sedation, and confusion. While many of these effects can be managed, it is important for clinicians to recognize that the presence of dementia may exacerbate some of these side effects. In general, we recommend that when a decision is made to initiate opioids in persons with dementia, a supervising family member or friend should be closely involved.

Tramadol, a drug with opioid properties, is commonly prescribed for the management of persistent pain and is associated with additional potential risks. In addition to opioid-related side effects, tramadol can also contribute to serotonin syndrome and lowers the seizure threshold.

| Parameter | Potential Benefit | Potential Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Pain | Reduced severity | No change in severity but exposure to potential risks |

| Polypharmacy | Reduced | Increased if concern about dependence/addiction |

| Caregiver burden | Improved | Heightened risk of falls |

| Cognitive function | Not known - perhaps reduced risk of delirium | May cause cognitive slowing as well as sedation; delirium is possible |

| Psychological function | May improve with reduction in pain | May cause depression and/or agitation |

| Appetite | Improved appetite may result if pain was interfering with appetite | Nausea and/or constipation may cause impaired appetite |

Step 5

Surgery.

Some patients with knee osteoarthritis that do not respond to other treatments are referred for knee replacement therapy. Knee replacement surgery has been shown to decrease pain and improve function and quality of life in appropriate patients. A diagnosis of dementia by itself does not preclude surgical consideration particularly in persons in the mild to moderate stages.

Different Treatment Options

Dr. Wright discusses with Mildred the cause of her pain and different treatment options available.