Mr. Wakefield is a young Army veteran with chronic low back pain and depression. His physical exam demonstrates musculoskeletal pain and lumbar facet arthropathy (joint pain in his lower back). He is referred by his physician for an initial psychological evaluation.

You are rotating with the psychologist who will be treating Mr. Wakefield. You are part of an inter-professional team composed of health care specialists from the following disciplines:

- Medicine

- Dentistry

- Pharmacy

- Nursing

- Psychology

Psychological Interview

Points to Remember

- Provide a rationale for psychological assessment

- Give the patient the opportunity to describe their symptoms in detail, including ALL of the complaints

- Normalize the pain experience, discussing the impact on the patient’s life

- Review depression symptoms, starting with biological symptoms: restless sleep and early morning awakenings, poor sleep hygiene, feeling helpless, decreased enjoyment of activities, decreased energy and concentration, current/past suicidal ideation and attempts, weight/appetite change

- Review anxiety/PTSD symptoms: Panic attacks, heart racing/palpitations, GI symptoms, fears of pain or activity, nightmares, flashbacks

- Assess risk of harm to oneself or others

- Review family history (medical, psychological, and substance use)

- Review recreational substance use, current and past, and including: alcohol, tobacco, illicit substances, misuse/abuse of prescription medications

- Assess behaviors that worsen or improve symptoms

- Inquire about adherence to past recommendations

- Address how fear of pain or movement-induced harm affects activity

- Ask about how others respond to reports of pain

- Reinforcing fear of pain or disability behavior (solicitous)

- Help distract attention from pain

- Punish or blame when reporting pain

- Assess presence of social supports

- Review current psychiatric care and symptoms being treated, e.g., PTSD symptoms

- Review pharmacotherapy adherence, beliefs about medications

- Review patient perception of disability

- Review patient expectations and beliefs about activity, including work

- Discuss patient goals and care coordination

Mr. Wakefield Speaks with the Pain Psychologist

Test Your Knowledge

The presence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder is best supported in Mr. Wakefield on the basis of:

Mr. Wakefield’s withdrawing from social activities is most likely related to:

Mr. Wakefield’s disability may be fueled by all of the following, EXCEPT...

Assessment Summary for Mr. Wakefield

Mental status

Alert, oriented, fluent speech.

Mood/Affect

Depressed, ruminative regarding his symptoms, anxious, pessimistic, self doubt, poor sleep, “doom and gloom” attitude, no suicidal thoughts.

Pain behaviors

Grimacing with movement, fidgets while seated, holding his lower back.

Other observations

Cooperative but frustrated by current physical status, nightmares, fearful of activity, and doesn’t think he’ll get better, history of heavy drinking while in service.

Psychological Considerations of Patients In Pain

Summary

Screening Tools

Psychological Assessment Domains

- Depression (PHQ-9)(pdf, 45 KB)

- Anxiety (Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale/HADS)(pdf, 37 KB)

- PTSD (PC-PTSD)

- Alcohol use (Audit-C)(pdf, 39 KB)

- Opioid Risk (SOAPP-R/COMM/ORT)(pdf, 111 KB)

- Substance Use Disorder (NIDA Quick Screen)(pdf, 242 KB)

- Disability (WHODAS-2/RMDQ)(pdf, 494 KB)

- Fear Avoidance Beliefs (FABQ)(pdf, 113 KB)

- Sleep (ESS)

Psychological Summary for Mr. Wakefield

Mr. Wakefield is a 29 year old Army veteran who served in Afghanistan with worsening chronic low back pain affecting his ability to function physically and emotionally on a daily basis. He demonstrates depressed mood, sleep disturbances, irritability, anxiety, and evidence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). He also has strong doubts (low self efficacy) in his ability to manage his pain and function which is contributing to his fear-avoidance fueled disability. He is socially isolated and spends most of the day in bed. Current treatments are ineffective and he is frustrated by his current status.

PTSD and Chronic Pain

What about PTSD and chronic pain?

- It is estimated that > 50% of veterans with PTSD have chronic pain, versus approximately 10% in the general population.

- PTSD is an often missed comorbidity if not suspected and appropriately assessed.

- A 2014 study in 241 veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain (of which 28% had comorbid PTSD and chronic pain and 72% had chronic pain only) demonstrated that:

- Veterans with comorbid chronic musculoskeletal pain and PTSD experienced higher pain severity, greater pain-related disability and increased pain interference, more maladaptive pain cognitions (e.g., catastrophizing, self-efficacy, pain centrality), and higher affective distress than those with chronic pain alone.

- Patients with chronic pain AND PTSD experience more disabling pain than those without PTSD

- The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs offers various resources surrounding PTSD and chronic pain: http://www.ptsd.va.gov/public/problems/pain-ptsd-guide-patients.asp

References

- Fishbain DA, et al. Chronic Pain Types Differ in Their Reported Prevalence of Post -Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and There Is Consistent Evidence That Chronic Pain Is Associated with PTSD: An Evidence-Based Structured Systematic Review. Pain Med 2016 (Epub ahead of print). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27188666

- Scioli-Salter ER, Forman DE, Otis JD, et al. The shared neuroanatomy and neurobiology of comorbid chronic pain and PTSD: Therapeutic implications. Clin J Pain 2015;31:363–74. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24806468

- Outcalt SD, et al. Pain experience of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans with comorbid chronic pain and posttraumatic stress. J Rehabil Res Dev 2014;51(4):559-70. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25144169

Poor Sleep and Chronic Low Back Pain

How is poor sleep a factor in chronic low back pain?

- Many studies report that > 50% of patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP) suffer from sleep disturbances and poor sleep quality

- Patients with CLBP spend < 5% of the time in stage 3 and 4 sleep (deep sleep) versus 20-25% of the time for patients without pain

- Depression is associated with sleep disorders and chronic low back pain

- Sleep and pain are cyclical and bidirectional; decreased sleep leads to increased pain and increased pain leads to decreased sleep

- In summary, decreased sleep and poor sleep quality leads to:

- Increased pain and hyperalgesia

- Decreased quality of life

- Decreased coping mechanisms

- Increased rate of hospitalizations

- And more…

References

- Kelly GA et al. The association between chronic low back pain and sleep: a systematic review. Clin J Pain 2011;27(2):169-81http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20842008

- Alsaadi SM et al. Erratum to: Prevalence of sleep disturbances in patients with low back pain. Eur Spine J 2012;21:554-560. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21863463

- Haack M, et al. Sustained sleep restriction reduces emotional and physical well-being. Pain 2005;119(1-3):56-64. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16297554

- Davies KA et al. Restorative sleep predicts the resolution of chronic widespread pain: results from the EPIFUND study. Rheumatology 2008; 47(12):1809-13. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18842606

- Sivertsen B, Lallukka T, Petrie KJ, et al. Sleep and Pain Sensitivity in Adults. Pain. 2015 Aug;156(8):1433-9.

- Bonvanie IJ, Oldehinkel AJ, Rosmalen JG, et al. Sleep problems and pain: a longitudinal cohort study in emerging adults. Pain. 2016 Apr; 157(4):957-63. Population research shows sleep problems in 18-25 year olds may predict the onset of chronic pain & its severity years later.

- Jungquist CR, Flannery M, Perlis ML, et al. (2012). Relationship of chronic pain and opioid use with respiratory disturbance during sleep. Pain Manage Nurs, 13 (2): 70-79.

- Finan PH, Goodin BR, Smith MT. The association of sleep and pain: an update and a path forward. J Pain. 2013 Dec;14(12):1539-52.

Behavioral and Psychological Approaches

Behavioral and psychosocial approaches are paramount to co-managing pain, mood disorders, and sleep disturbances.

Example Behavioral Approaches

Dr. Bob Jamison speak about example behavioral approaches for managing Mr. Wakefield’s symptoms.

Summary of important behavioral considerations in managing Mr. Wakefield

- “Normalize” the presence of depression symptoms with pain and the value of pursuing behavioral options

- Establish realistic treatment goals to help patients to improve mood, sleep, function, and physical activity

- Click here for “S.M.A.R.T.” guide for setting goals

- Use relaxation/meditative techniques to help lessen pain

- Address worrying thoughts and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder

- Motivate him to empower himself

- Implement problem-solving techniques to address fear-avoidance of social and physical activity

- Implement graded activity to maximize physical capacity

Reference

Tichelaar J, Uil den SH, Antonini NF, van Agtmael MA, de Vries TP, Richir MC. A 'SMART' way to determine treatment goals in pharmacotherapy education. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016 Jul;82(1):280-4.

Meditation and Pain

Does meditation really work? Yes!

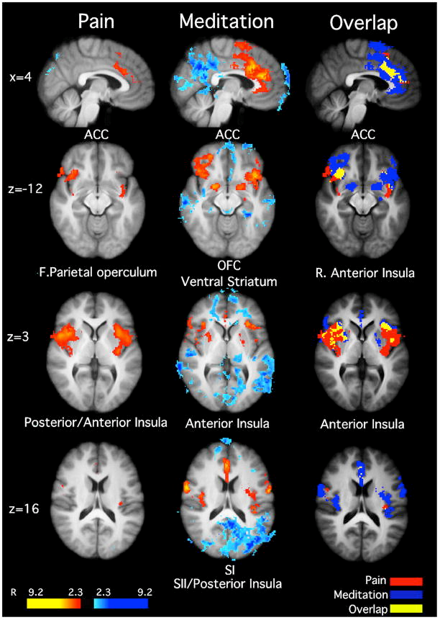

Meditation helps to separate the sensation of pain from the thoughts about pain.

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) can identify areas in the brain that influence a patient’s pain perception. This 2011 study demonstrated that after four-days of mindfulness meditation training, meditating in the presence of noxious (painful) stimulation significantly reduced pain-unpleasantness by 57% and pain-intensity ratings by 40% when compared to rest. fMRI images further illustrate how meditation deactivates pain signaling and activates pain modulating centers in the brain that help to decrease pain.

Reference

Zeidan F,et al. J Neurosci. 2011; 31(14):5540-8.

Importance of Graded Activity, Goal Setting, and Physical Rehabilitation in Mr. Wakefield

- Formal functional restoration (FR) rehabilitation programs offer an effective alternative to passive rehabilitation therapies

- FR programs focus on increasing exercises and activities “despite” pain and include physical/occupational, behavioral, pharmacotherapeutic, and interdisciplinary assessment and treatment strategies

- The patient learns that increased pain or “hurt,” does not equal “harm,” or injury, as fear-avoidance of activity is diminished

- Aerobic exercise, strength training, and specific activities are always “quota-based,” progressing in small increments, e.g., walking with two minute increases 3x per week regardless of pain; increases are never based on “pain,” “tolerance,” or “energy”

- “Pain behaviors” such as complaints of pain, grimacing, PRN medications, or laying down are not reinforced or prohibited in structured FR programs

- Goals are pre-established and specific, such as walking the dog 3x per week by week 6 or lifting a 25 pound niece by week 4, and pain is “no excuse”

- Return to work or establishing a “work capacity” by the program’s endpoint is a common goal for FR programs

Reference

Gatchel RJ, Mayer TG. Evidence-informaed management of chronic low back pain with functional restoration. Spine J 2008; 8(1):65-9.

Overview of Behavioral and Psychosocial Therapeutic Approaches

Many different psychosocial approaches may be used in Mr. Wakefield. Examples include:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

- Strong evidence base in many populations

- Promotes adaptive cognition, emotion and behaviors

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

- Emerging evidence it may work quicker/better that CBT

- Coping Skills and Self-management Training

- Meditation (many techniques from traditional to mindfulness)

- Activity-Pacing

- Biofeedback

- Many forms emerging via smartphone apps and the internet

References

- Crawford C, Lee C, Buckenmaier C 3rd, Schoomaker E, Petri R, Jonas W; Active Self-Care Therapies for Pain (PACT) Working Group. The current state of the science for active self-care complementary and integrative medicine therapies in the management of chronic pain symptoms: lessons learned, directions for the future. Pain Med. 2014 Apr;15 Suppl 1:S104-13.

- Nakata H, Sakamoto K, Kakigi R. Meditation reduces pain-related neural activity in the anterior cingulate cortex, insula, secondary somatosensory cortex, and thalamus. Front Psychol. 2014 Dec 16;5:1489. Accessed 8/22/15 on line at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4267182/

- Ehde DM, Dillworth TM, Turner JA Cognitive-behavioral therapy for individuals with chronic pain: efficacy, innovations, and directions for research. Am Psychol. 2014 Feb-Mar;69(2):153-66

- Glombiewski JA, Bernardy K, Häuser W. Efficacy of EMG- and EEG-Biofeedback in fibromyalgia syndrome: A meta-analysis and a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013; 2013:962741. Accessed on line 8/24/15 at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3776543/

- Andrasik F. Biofeedback in headache: an overview of approaches and evidence. Cleve Clin J Med. 2010 Jul;77 Suppl 3:S72-6.

- Hatchard T, Lepage C, Hutton B, Skidmore B, Poulin PA. Comparative evaluation of group-based mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment and management of chronic pain disorders: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis with indirect comparisons. Syst Rev. 2014 Nov 10;3:134. Accessed on line 8/23/15 at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4230908/