Maximizing Opioid Safety

Charlie takes an altered prescription for 40 tablets to the local pharmacy.

While watching the clinical vignette did you feel the prescription issued was for a legitimate medical purpose? What additions to the prescription could increase security?

Test Your Knowledge

Maximizing Security of a Prescription for a Controlled Substance

The following additions to the controlled substance prescription could increase security:

Suspected Alteration

What should the pharmacist do if there is suspected altering of a controlled substance prescription?

Focus on Opioid Safety

It is important for all interprofessional team members to maximize opioid safety.

Opioid safety includes attention to the following:

- Understanding the controlled substances schedules

- Appropriate opioid prescribing

- Writing the controlled substance prescription

- Optimal storage for opioids

- Reducing opioid misuse, abuse, and diversion

Controlled Substances Schedules

Per the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, there are five schedules or classes of controlled agents. Whether a drug should be classified as belonging to one schedule versus another is determined by three factors. The first factor pertains to whether the substance has a legitimate medical use in the United States. Schedule 1 agents have not been approved for medical use in the United States, whereas agents belonging to Schedules 2 through 5 are approved for medical use.

The second factor concerns the substance’s abuse potential. Scheduled numbers vary inversely with abuse potential such that the potential for abuse of a Schedule 1 drug is greater than that of Schedule 2 drugs; Schedule 2 drugs greater than that of Schedule 3 drugs, and so forth.

The last factor relates to the substance’s dependency potential. As with abuse potential, schedule numbers vary inversely with the potential for dependency. Schedule 1 drugs are those with high abuse potential and no acceptable medical uses. Examples include heroin, LSD, peyote and marijuana.

Schedule 2 medications are those with acceptable medical use, but with a high abuse potential that may lead to severe dependence. These examples include morphine, methadone, amphetamine and oxycodone prescriptions. Prescriptions written for these medications cannot be transmitted by phones to pharmacies and cannot be written for refills.

Schedule 3 medications are those with less abuse potential and a moderate risk for dependency. Examples of these medications include buprenorphine and ketamine. These medications can be refilled for five times within a six-month period, whichever comes first.

Schedule 4 medications are those with a lower abuse potential. Examples include alprazolam (or Xanax), temazepam (or Restoril) and zolpidem (or Ambien). Refill limitations are the same as Scheduled 3 medications. Lastly, Scheduled 5 medications are those that contain a limited quantity of a controlled substance. These usually include codeine-containing products such as Phenergan VC.

| Schedule | Medical use in the US | Abuse Potential | Dependency Potential | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | No | High | Lack of accepted safety for use | Heroin, LSD, peyote, marijuana (LSD: Lysergic acid diethylamide (street name: acid) |

| II | Yes | High | Severe | Morphine, Methadone, Amphetamines, hydrocodone/acetaminophen (Vicodin®) |

| III | Yes | Moderate | Moderate | Buprenorphine, Ketamine, Codeine/acetaminophen (Tylenol #3®) |

| IV | Yes | Moderate-Low | Limited | Barbital, Alprazolam (Xanax®) |

| V | Yes | Moderate-Low | Limited | Codeine containing products (ex: Phenergan VC with codeine®), Atropine/diphenoxylate (Lomotil®) |

Reference

Office of Diversion Control, Drug Enforcement Administration, U.S. Department of Justice. Controlled substances schedules. [cited 2016 Sep 09]. Available from: http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/schedules/

Appropriate Opioid Prescribing

- Consider, at each patient interaction, if opioids are appropriate

- Balance potential risks, and realistic benefits, of therapy

- As previously mentioned, set expectations for therapy, and how the opioids will be discontinued if “unsuccessful”

- Consider lowest effective dose

Writing the Prescription

When writing a prescription for a controlled substance there are important parameters that must be included. As we’ve seen in the clinical vignette one additional way to improve security of a prescription for a controlled substance is to consider writing the number of tablets or capsules being prescribed in letters next to the numeric note. By adding each of these parameters, it can reduce the ability for a patient, or others, to modify or adulterate the script.

Important to include when writing the prescription:

- Opioid formulation

- Number of tablets/capsules

- Consider writing number as well

- Dose (mg)

- Directions

- Refills

Optimal Storage for Opioids

After opioids are dispensed it is also appropriate to counsel patients on the optimal storage. These medications should be stored in a cool, dry, safe place.

To ensure security, healthcare team members should also consider encouraging patients to use lockboxes.

These lockboxes can be found on the Internet, or ordered through some patients’ health system’s pharmacies or insurance plans. Without insurance they range from $10 to $60. One myth surrounding the optimal storage of opioids is that as healthcare practitioners, we discourage the use of pillboxes for the storage of opioid drugs. This is because pillboxes can challenge the integrity of opioid security, allowing easy access to people who were not prescribed the opioid medication. Instead, we encourage patients to store these medications in the original vial and out of the reach from those not prescribed the opioid.

When considering safe storage for prescription opioids, include the following:

- Cool, dry place

- Ensured security

- Consider lockboxes. Example includes the Lock Med locking storage container

- Discourage pillboxes, as these can challenge the integrity of opioid security

Reducing Potential Opioid Misuse, Abuse and Diversion

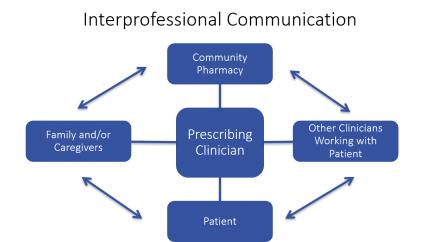

As seen in the clinical vignette interprofessional communication is the key to reducing potential opioid misuse, abuse and diversion. It is important for the prescribing clinician to be in contact with the patient’s community pharmacist, other clinicians working with the patient, the patient themselves, and their families or caregivers. In today’s healthcare system there are many operational barriers to this interprofessional communication. However, it is important to sustain these lines of communication to reduce this epidemic.

Tools Available to Community Pharmacists

In regards to reducing potential opioid misuse, abuse, and diversion, community pharmacists have two tools available to them.

- Scrutinize the physical prescription and clinical situation (i.e., search for red flags)

- Utilize prescription drug monitoring programs (varies by state)

Red Flags for Community Pharmacists

Community pharmacists must scrutinize both the physical prescription as well as the clinical situation for red flags.

These include:

- Early "refills"

- Multiple prescriptions from different providers

- Modification or adulteration of the prescription

- Patient looking disheveled or unorganized when picking up prescriptions

- Patient presenting at time of closing, paying for prescriptions in cash (or requesting not to go through insurance)

- Receiving multiple prescriptions for controlled substances that may not therapeutically make sense

This list is not all-inclusive and it is up to the community pharmacist’s clinical judgment to examine both the prescription and clinical situation for things that seem out of place.

Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs)

Prescription drug monitoring programs are online databases that collect information regarding the controlled substances dispensed within a certain state. Currently, 49 states have an operational prescription drug monitoring program, or have enacted legislation. It is important to note that prescription drug monitoring programs vary in regards to their implementation stages, operations and goals. As of 2014 Pennsylvania enacted legislation (referred to as Act 191) to improve the Pennsylvania prescription drug monitoring program.

- Online databases that collect information regarding controlled substances dispensed within a certain state

- Currently 49 states have an operational PDMP, or have enacted legislation

- Varying implementation stages, operations and goals

- Pennsylvania: legislature passed Act 191 (of 2014)

- Varying implementation stages, operations and goals

Pennsylvania PDMP

In Pennsylvania the prescription drug monitoring program is overseen by the Pennsylvania Department of Health. As of late August 2016 prescribers and dispensers will be able to register into the prescription drug monitoring program. Prescribers, dispensers, and their delegates will have real-time access to this information. Community pharmacies or other dispensers of controlled substance prescriptions must report this information into the system within 72 hours of the controlled substance being dispensed. If a dispenser has the date that the prescription was sold or picked up, they can also report that. This is only possible if the pharmacy has a point of sale system that is integrated with the pharmacy management system to allow a bidirectional flow of information. If the date of the prescription sold is not available, submitting the date the prescription was filled is sufficient.

A dispenser is a person licensed to dispense in the state of Pennsylvania; these include both mail order and the internet sales of controlled substances. There are some exemptions from this requirement, such as a correctional facility, if the confined person cannot lawfully visit a prescriber outside the correctional facility; a wholesale distributor of controlled substances; or, lastly, a veterinarian.

There are two controversies surrounding the Pennsylvania prescription drug monitoring program. The first is if a dispenser or community pharmacy should require identification from a patient when a controlled substance prescription is picked-up. Currently this is not required. The second surrounds what essentially is deemed suspected opiate misuse, abuse or diversion, as there is no clear cut-off in regards to number of tablets dispensed, milligrams per day, or how many prescriptions a patient can fill in a certain period of time.

- Responsible party: PA Department of Health

- Pertinent Information:

- Prescribers and dispensers will be able to register starting in late August 2016

- Prescribers, dispensers, and their delegates will have "real-time" access

- Dispensers must report information to the system within 72 hours of being dispensed

- Prescribers and dispensers will be able to register starting in late August 2016