The Experience of Pain

- Pain is a subjective, internal, & personal experience that cannot be directly observed by others or exclusively understood in terms of tissue damage detected via physiological markers or bioassays.

- Pain assessment almost exclusively relies upon the use of self-report measurements.

- Objective measures of pain?

Challenges of Pain Assessment

Pain assessment requires valid & reliable instruments in addition to the capability to communicate via language, movements, etc.

- Difficulties:

- Timing: various instruments querying about pain at present or pain during the previous week. Longer time frames are also used, which may introduce memory biases.

- Pain is a multidimensional experience that incorporates both sensory and affective components that, though correlated, can (or should) be separately assessed.

- Most of the self-report pain assessment instruments used in clinical practice focus on pain intensity ratings (a quantitative estimate of the severity or magnitude of perceived pain) over a relatively brief and recent time period (e.g., the past week).

Pain Assessment Methods

Three most commonly used methods to quantify the severity or magnitude of perceived pain:

- Verbal rating scales

- Numeric rating scales

- Visual analogue scales

Verbal Rating Scales (VRS)

- Comprised of adjectives/phrases that characterize different levels of pain intensity. (e.g., None, Mild, Moderate, Severe, Very Severe)

- Descriptors arranged from least to most intense (or unpleasant).

- Maximum possible range of the pain experience (e.g., from “no pain” to “extremely intense pain”) should be spanned.

- Scored by arranging descriptors in order of severity & assigning them a numerical value according to their rank (e.g., 0–4).

Advantages

- Simple & easy to administer & score.

- Face validity (appears to measure exactly what it claims - pain intensity).

- Demonstrated good reliability in various studies

- Frequently positively correlated with other pain intensity self-report measures & pain behaviors (establishing its validity).

- Compliance rates for the VRS are generally better than those obtained with other scales due to the fact that they are so easy to comprehend, which can also be particularly useful with certain populations such as the elderly.

Disadvantages

- Scoring assumes equal intervals between adjectives, such that a change in pain from “none” to “mild” is quantified identically as the change from “moderate” to “severe”.

- Problematic if patient is not familiar with all of the words and/or unable to find a descriptor that accurately describes their pain.

Numerical Rating Scales (NRS)

- NRSs are simple & direct: ask patient to rate their pain intensity on a NRS.

- NRSs consist of a range of numbers from 0 to 10 or 0 to 100, anchored with 0 indicating ‘no pain’ and 10 or 100 (or whatever the maximum numerical value is) representing ‘the most intense pain imaginable’.

- NRS correlates positively with other pain measures & is sensitive to changes arising from the treatment of pain.

- NRS can be administered in different formats (i.e., verbally or written).

- Easy & practical to administer & score.

- Non-intrusive method of measuring pain.

- Easy to understand.

- NRS scales are also sensitive to treatment-related changes.

- The main weakness of the NRS is that, statistically, it does not have ratio qualities.

An example of a numeric pain rating scale can be found at https://www.sralab.org/rehabilitation-measures/numeric-pain-rating-scale

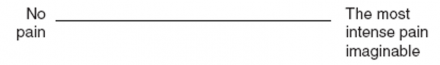

Visual Analogue Scales (VAS)

- VAS is a variation of NRS & typically consists of a 10 cm long horizontal line with the ends anchored at “no pain” on the left & “the most intense pain imaginable” on the right.

- VAS does not contain marked intervals

- Patients indicate pain intensity by marking a point on the line between “no pain” & “the most intense pain imaginable” & the results are essentially treated like ratio data.

- Patient’s pain is measured as the distance from “no pain” to the point on the line representing their pain intensity.

- Studies conducted in clinical settings support the reliability and validity of the VAS as well as its sensitivity to treatment effects.

- Research generally indicates that there are minimal differences in sensitivity among the VAS, VRS, & NRS.

- When significant differences are found they usually suggest that the VAS is more sensitive than other instruments.

- VAS scores have been shown to correlate with pain behaviors & they also appear to possess ratio-level scoring properties

Visual Analogue Scale

Disadvantages

- Scoring is more time-intensive, & involves several steps (i.e., a VAS is scored using a ruler in which the score is the number of centimeters or millimeters from the end of the line) which consequently increases the likelihood of committing an error.

- VAS can also be difficult to administer to patients with impaired motor functioning, a condition not uncommon when working with chronic pain populations.

- Research also indicates that compared to other pain intensity rating scales the VAS is difficult to understand particularly for individuals with cognitive disabilities as well as for elderly populations. The result is higher non-completion rates among these samples.

McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ)

- Widely-used for multidimensional pain assessment.

- Though originally intended to be administered verbally, it is frequently given as a paper-and-pencil questionnaire.

- MPQ was derived from the assumption that pain possesses 3 primary dimensions: sensory-discriminative, affective-motivational, and cognitive-evaluative.

- Comprised of 20 sets of verbal descriptors, ranked in terms of pain severity from lowest to highest. The groups of descriptors are divided into those assessing the sensory (10 sets), affective (5 sets), evaluative (1 set), and miscellaneous (4 sets) dimensions of pain.

- Respondents select the words best capturing their pain, which are then converted into a pain rating index, based on the sum of all of the words after they are assigned a rank value, as well as the total number of words chosen.

- MPQ-SF is more frequently used than the parent MPQ scale.

- MPQ-SF is:

- Highly correlated with the original scale,

- Able to discriminate among different pain conditions,

- May be easier to use with geriatric patients than parent scale

Behavioral Observation

- Pain behaviors include: facial expressions (e.g., grimacing), vocalizations (e.g., moaning), body postures (e.g., hunching over), & behaviors (e.g., rubbing/massaging pain site).

- Pain behaviors are an important component of behavioral models of pain.

- A multitude of methods exist to code pain behaviors, though a number of them are specific to particular pain conditions.

- Assessing pain behaviors important when:

- Determining a patient’s level of physical functioning (e.g., how much activity they engage in),

- Understanding the factors that may reinforce pain behaviors (e.g., solicitous responses from others),

- In evaluating pain in nonverbal individuals.

- Research indicates that although there is a moderate relation between self-report of pain & pain behaviors, they are not interchangeable.

- The association between self-reports of pain intensity & pain behavior is lower in the context of chronic pain relative to acute pain

- It is greatest when observations of pain behaviors & verbal reports of pain are recorded simultaneously.

Experimental Pain Assessment

- Administration of standardized aversive stimulation within a laboratory to examine the relationships of aversive stimuli to behavioral & sensory perceptions is a sub-discipline in the pain field.

- There are various forms of noxious stimulation that are employed to cause pain (e.g., thermal, mechanical, electrical, chemical, ischemic, etc.).

- Outcome measures generally include pain threshold, pain tolerance, and ratings of suprathreshold noxious stimuli using an NRS, a VAS, or a VRS.

- The clinical relevance of experimental pain assessment is being determined; quantitative sensory testing can be used to subtype patients with chronic pain conditions, identify mechanisms & prospectively predict postoperative pain.

Psychophysiological Assessment

- EMG has been used to record levels of local muscle tension in the context of musculoskeletal pain syndromes (e.g., low back pain, tension headache, etc.)

- EEG has been used in various studies to measure cortical responses to noxious stimulation. Though the spatial resolution of EEG is somewhat limited, its temporal resolution is actually rather good; multiple studies have recently shown that brain responses to standardized noxious stimuli measured by EEG are enhanced in patients with chronic pain compared to healthy controls.

- Heart rate & BP are also often assessed in the context of laboratory pain testing.

- However, while pain responses & resting blood pressure are inversely related, no consistent associations between cardiovascular reactivity pain responses have yet been observed.

- Collectively, psychophysiological measures can provide unique information about pain responses, but they do not constitute an “objective” measurement of an individual’s pain experience.

Objective Measures of Pain

Wager, TD, Atlas, LW, Lindquist, MA, Roy, M, Woo, CW, & Kross, E (2013). An fMRI-Based Neurologic Signature of Physical Pain. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1388-1397

- Controversial study: e.g., congenital insensitivity to pain, psychogenic pain, subjective experience

- Pros: infants, non-verbal

- Negative: misuse in court cases, workman’s comp

Special Populations: Children

- Pain assessment in children can present numerous challenges.

- Treatment providers often mistakenly assume that children are unable to provide accurate or reliable information about their pain experience.

- In fact, numerous pain assessment tools for use specifically in children have been developed & validated.

- Further, factors similar to those influencing pain in adults (e.g., degree of tissue damage, mood states, social responses, etc.) have also been shown to relate to children’s pain in comparable ways.

- Various behavioral pain rating scales for infants have been developed & validated.

- Example: Neonatal Infant Pain Scale (NIPS), codes the presence & intensity of 6 pain-related behaviors: facial expressions, crying, breathing, arm movement, leg movement, & arousal state.

- Standardized pain assessment instruments for children of different ages have been developed b/c direct questioning of sensory & affective experiences can be particularly susceptible to bias and demand characteristics.

- The Faces scale & the Oucher scale are 2 examples that are intended for use with younger children who may be preverbal.

- Other types of widely used pain measurement instruments designed for use with children include pain thermometers, comprised of a vertical NRS that is superimposed on a VAS shaped to resemble a thermometer, though a standard VAS is a valid and reliable pain measurement instrument for children older than six years of age.

Faces Pain Scale

Reference

The FACES pain scale. Reprinted with permission from Bieri D, Reeve RA, Champion GD, et al: The Faces Pain Scale for the self-assessment of the severity of pain experienced by children. Pain 41:139–150, 1990.)

Special Populations: Elderly

- Majority of pain assessment instruments validated in middle-aged adults have also been psychometrically evaluated in older subjects.

- Increasing age is associated with a higher frequency of incomplete or unusable responses on a VAS, though not on a VRS or NRS.

- Across different studies, rates of difficulty with the VAS (i.e., incomplete or unusable data) in cognitively intact samples of elderly subjects range from 7% to 30%, with the percentages substantially increasing (up to 73%) in cognitively impaired samples.

- Studies examining elderly respondents’ preferences of pain measurement instruments indicate that VRSs frequently receive the highest preference scores while VASs have been rated as one of the least preferred pain measures.

- Also, the long form of the MPQ is not appropriate for use with elderly patients due to its level of complexity and time requirements.

- Multiple studies have determined that older adults report less pain on the MPQ (i.e., choose fewer words) even when NRS or VRS-rated pain does not differ. These results may suggest that the MPQ differentially assesses the construct of pain as a function of age, suggesting that caution may be warranted when using this pain measurement instrument with older populations.

- Collectively, recent findings suggest that the fewest “failure” responses among samples of cognitively intact & cognitively impaired elderly subjects are produced with the VRS while the largest number is produced with a VAS.

- Consequently, it is recommended that studies investigating pain in elderly samples use, at minimum, a VRS to assess pain intensity.

Biases in Pain Measurement

- Consequences of inaccurate measurements of pain can be substantial.

- Underestimation of pain can potentially lead to improper management, unnecessary suffering, & delays in recovery.

- Overestimation of pain can potentially lead to over-treatment and possible adverse iatrogenic consequences.

- Numerous studies have investigated the correspondence, or lack thereof, between patients’ reports of pain & healthcare providers’ assessments of patients’ pain. Generally, the results from this line of research indicate that substantial caution is warranted when healthcare professionals attempt to estimate patients’ pain levels.

In addition to findings associated with the inaccuracy or underestimation of patients’ pain, there exists little evidence supporting the validity of expert judgments regarding pain patients’ prognosis. For example, there was no congruence between treatment providers’ estimates of patients’ rehabilitation potential and actual rehabilitation outcomes among back pain patients that were followed longitudinally.

Summary

- A wide range of valid & reliable measurement instruments is available to assess pain despite the fact that pain is a private and subjective experience.

- The use of a VRS or NRS over a VAS is strongly recommended in studies using elderly or cognitively impaired subjects.

- Behavioral observation, laboratory pain assessment, & psychophysiological assessment are all useful and potentially informative adjunctive measures of pain responses, however, none can substitute for the patient’s self-report of the pain experience.

- The assessment of pain in infants is the exception to this standard, where the coding of behavioral or facial expressions/responses is presently the gold standard for pain assessment.

- There is substantial research indicating that healthcare providers, regardless of experience, are unreliable judges of patients’ report of pain.

- Treatment providers tend to frequently underestimate patients’ experiences of pain.