Equianalgesic Dosing

Equianalgesic Example

From this table, you can compare potencies or "strengths" between the different opioids.

For instance, oral hydromorphone is more potent than oral oxycodone, which is more potent than oral morphine. Thus, lower doses of hyrdomorphone are needed for a similar effect of a higher dose of oxycodone.

| Oral/Rectal Dose (mg) | Opioid Analgesic | Intravenous Dose (mg) |

|---|---|---|

| 30 | Morphine | 10 |

| 0.4 | Buprenorphine | 0.3 |

| 200 | Codeine | 100 |

| N/A | Fentanyl | 0.1 |

| 30 | Hydrocodone | N/A |

| 7.5 | Hydromorphone | 1.5 |

| 20 | Oxycodone | N/A |

| 100 | Tramadol | N/A |

Equianalgesic Fentanyl

Calculations for transdermal fentanyl should be made based on the manufacturer's recommendations using the table below.

| Oral 24-Hour Morphine Equivalent (mg/day) | Transdermal Fentanyl Dose (mcg/hour) |

|---|---|

| 60-134 | 25 |

| 135-224 | 50 |

| 225-314 | 75 |

| 315-404 | 100 |

| 405-494 | 125 |

| 495-584 | 150 |

| 585-674 | 175 |

| 675-764 | 200 |

| 765-854 | 225 |

| 855-944 | 250 |

| 945-1034 | 275 |

| 1035-1124 | 300 |

Equianalgesic Methadone

There are numerous calculation methods for conversion to methadone. One method commonly used in practice is listed below.

| Oral 24-Hour Morphine Equivalent (mg/day) | Oral Dose Ratio (Morphine:Methadone) |

|---|---|

| greater than 100 | 3:1 |

| 101-300 | 5:1 |

| 301-600 | 10:1 |

| 601-800 | 12:1 |

| 801-1000 | 15:1 |

| greater than or equal to 1001 | 20:1 |

Pain Information

- International Association for the Study of Pain: http://www.iasp-pain.org/

- American Pain Society: http://americanpainsociety.org/

- Academy of Integrative Pain Management: http://www.aapainmanage.org/

- American Academy of Pain Medicine: http://www.painmed.org/

- American Chronic Pain Association: https://theacpa.org/

- National Fibromyalgia and Chronic Pain Association: http://www.fmcpaware.org/

Assessment Tools

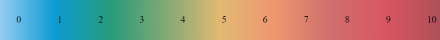

11-point Numerical Rating Scale (NRS)

There are several different scales that can be used to assess for pain severity.

The most common is the 11-point Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), which uses the range 0-10. The benefits of the NRS are its simplicity and validity. Possible drawbacks include response variability and moderate correlation with functional status.

Opioid Risk Tool

Link opens a PDF version of the Opioid Risk Tool.

Numeric Risk Tool

Link opens a PDF version of the Numeric Risk Tool.

Quick DASH

Link opens a PDF version of the QuickDASH.

Functional Pain Scale (FPS)

Instructions:

Ask the patient if pain is present. If the patient has pain, ask him or her to rate the pain subjectively as either "tolerable" or "intolerable."

Finally, find out if the pain interferes with function.If the patient rates the pain as "tolerable," establish whether the pain interferes with any activity. If the pain is "intolerable," determine whether the pain is so intense as to prevent passive activities. See the chart below for guidelines.

- 0 No pain

- 1 Tolerable (and does not prevent any activities

- 2 Tolerable (but does prevent some activities

- 3 Intolerable (but can use telephone, watch TV, or read)

- 4 Intolerable (but cannot use telephone, watch TV, or read)

- 5 Intolerable (and unable to verbally communicate because of pain)

Scoring:

The patient's subjective rating of pain and the objective determination of the pain's interference with activities will produce a corresponding score on a scale of 0-5.

A lower score equates to less severe pain and less interference with functional abilities, if any. Ideally, all patients should reach a 0 to 2 level, preferably 0 to 1.

It should be made clear to the respondent that limitations in function only apply if limitations are due to the pain being evaluated.

Source:

Gloth FM III, Scheve AA, Stober CV, Chow S, Prosser J. The Functional Pain Scale: reliability, validity, and responsiveness in an elderly population. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2001;2(3):110-114.

OPQRST

When assessing pain, it is important to ask certain questions in order to get a full understanding of the patient’s pain history. There are different methods you can use to remember the important questions to ask. One option is the pneumonic “OPQRST.”

O – Onset: When did the pain start? What was happening at that time?

P – Palliative and Provocative factors: What makes the pain better? Worse? (Include specific activities, positions or treatments.)

Q – Quality: Describe the pain. Is it burning, sharp, shooting, aching, throbbing, etc.?

R – Region and Radiation: Where is the pain? Does it spread to other areas?

S – Severity: How bad is the pain? (There are several scales to use, which will be discussed in the following slide)

T – Timing: When does the pain occur? Has it changed since onset? If so, how?

Reference:

Powell RA, Downing J, Ddungu H, Mwangi-Powell FN. Pain Management and Assessment. In: Andrea Kopf NBP, editor. Guide to Pain Management in Low-Resource Settings. Seattle: IASP: International Association for the Study of Pain; 2010. p. 67-79 http://www.iasp-pain.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Home&TEMPLATE=/CM/HTML….

Screening

Ask, "Are you experiencing any discomfort right now?"

If No: document “zero” pain and reassess periodically

If Yes: ask about its nature (verbal description) pattern (over time) and location

Try to quantify the intensity of the pain, show the patient the rating tools we use and determine which one is easiest and most meaningful for them.

Try to quantify the intensity of the pain, show the patient the rating tools we use and determine which one is easiest andmost meaningful for them.

Starting with the Numeric Risk Tool (remember, this is an eleven point scale of 0-10, not 1-10), ask the patient if they would recognize:

- if the discomfort were completely gone ("a rating of 0")

- or the worst they or anybody else could possibly experience ("10")

Have the patient rate the intensity of their pain/discomfort "right now" verbally with a number of by pointing to the number that represents their pain intensity.

Once the patient understands this scale, follow-up questions may be tried without the visual aid:

- "On a scale of 0 to 10, how much pain (or discomfort) are you experiencing now?"

If the Numeric Risk Tool is not easy and meaningful, use the Verbal Descriptor Scale:

- Determine if discomfort is "none" (chart 0) or the worst possible (chart 10).

- Ask if the discomfort or pain is mild, moderate, severe, or extreme.

-

- Record 2 (for mild), 4 (for moderate), 6 (for severe), or 8 (for extreme) accordingly.

- If the patient reports it's between two words, select the odd number between them (e.g. the score of a report of pain between mild and moderate = 3)

If that isn't easy and meaningful, use the Functional Pain Scale.

Determine if it is tolerable ("less than or equal to 5") or intolerable ("greater than or equal to 5").

- Tolerable pain that does not interfere with activities = 2

- Tolerable pain that interferes with physically demanding activities = 4

- Intolerable pain that interferes with physically demanding activities = 5

- Intolerable pain that interferes with active but not passive activities = 6

- Intolerable pain that interferes with passive acitivities (e.g. reading) = 8

- Pain so severe the patient can't do any active or passive activities (e.g. can't even talk about pain without writhing/screaming) = 10

Reassess using the 4-A's determining safety and efficacy of therapy:

- Analgesia: To what extent did the treatment reduce the pain and make it more tolerable? This can be evaluated using one of the pain intensity scales above, the percent that pain intensity is reduced by (e.g., 30%, 50%, etc.) or adjectives (good, excellent effect) the patient uses.

- Activity: To what extent did the patient's activity and rest patterns improve as a result of the treatment? Does pain interfere less with usual and prescribed therapeutic (e.g. physical therapy) activity? Does pain interfere less with sleep? Does the treatment affect safety?

- Adverse effects: What side effects, toxicity, technology-related complications are experienced?

- Aberrant behaviors: Has the medication affected medication-focuxed behaviors or personality?

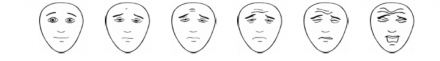

The Faces Pain Scale can also be used for any patient, but is especially useful with children or non-verbal patients. This is a well-studied and validated scale.

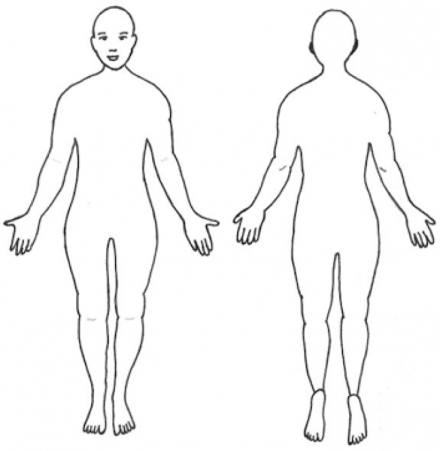

A body diagram can allow patients to pinpoint their pain site(s) to help guide your examination.

Additionally, observing patients when they move or during the exam is a useful addition to these scales, and is essential with young children and non-verbal adults.

Physical manifestations associated with acute pain, opioid withdrawal and opioid overmedication should be distinguished.

The table below matches the signs and symptoms to their corresponding condition(s) so you can see the similarities and differences for each condition.

| Signs/Symptoms | Acute Pain | Opioid Withdrawal | Opioid Overmedication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tachycardia (fast heart rate) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Hypertension (high blood pressure) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Disphoresis (sweating) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Vasoconstriction (cold hands/feet) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Mydriasis (dilated pupils) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Tremors (shaking) | No | Yes | No |

| Dysphoria/anxiety (emotional state characterized by depression, anxiety, unease) | No | Yes | No |

| Flu-like symptoms (runny nose, congestion, malaise, etc.) | No | Yes | No |

| Depression (low mood) | No | Yes | No |

| Diarrhea/vomiting | No | Yes | No |

| Respiratory Depression (low respiratory rate) | No | No | Yes |

| Bradycardia (low heart rate) | No | No | Yes |

| Miosis (constricted pupils) | No | No | Yes |

| Vasodilation (warm extremities) | No | No | Yes |

| Myclonic jerks (sudden muscle contractions/twitches) | No | No | Yes |

Institute of Medicine Report

In 2011, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a report regarding pain as a public health problem in the United States. The IOM recommended relieving pain become a national priority [9].

National Pain Strategy

In 2016, The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services outlined the nation’s first coordinated plan for reducing chronic pain in The National Pain Strategy (NPS). It was developed by a diverse team of experts from around the nation. The National Pain Strategy is a roadmap toward achieving a system of care in which all people receive appropriate, high quality and evidence-based care for pain [10].

Opioid Prescribing Guidelines

CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain

In 2016, the Center for Disease Control released the guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain.

Overview:

- Decrease opioid use for management of chronic noncancer pain

- Not applied for acute pain

- Recommend keeping doses lower, guiding therapy with functional assessments and maximum daily doses of opioids

All patients receiving chronic opioids should:

- Have an opioid use agreement

- Undergo routine urine drug screening based on risk for substance use disorder

Access the Pennsylvania Opioid Prescribing Guidelines.

Access the Washington State Opioid Prescribing Guidelines.

Reference:

CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain | Drug Overdose | CDC Injury Center. Cdc.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html. Published 2018. Accessed July 26, 2018.

Additional References Used In Module

- Ahmadi A, Bazargan-Hejazi S, Heidari Zadie Z, et al. Pain management in trauma: A review study. J Inj Violence Res. 2016;8(2):89-98.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

- Ankle Block. Dvcipm.org. https://www.dvcipm.org/site/assets/files/1083/chapt22.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed July 26, 2018.

- Ankle Fracture. Aofas.org. http://www.aofas.org/footcaremd/conditions/ailments-of-the-ankle/Pages/Ankle-Fracture.aspx. Published 2018. Accessed July 26, 2018.

- Argoff CE, Alford DP, Fudin J, et al. Rational urine drug monitoring in patients receiving opioids for chronic pain: Consensus recommendations. Pain Med. 2018;19(1):97-117.

- Bussieres AE, Stewart G, Al-Zoubi F, et al. The treatment of neck pain-associated disorders and whiplash-associated disorders: A clinical practice guideline. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(8):523-564.e27.

- Carroll KM, Onken LS. Behavioral therapies for drug abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(8):1452-1460.

- CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain | Drug Overdose | CDC Injury Center. Cdc.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html. Published 2018. Accessed July 26, 2018.

- Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10(2):113-130.

- Dever C. Treating acute pain in the opiate-dependent patient. J Trauma Nurs. 2017;24(5):292-299.

- Goost H, Wimmer MD, Barg A, Kabir K, Valderrabano V, Burger C. Fractures of the ankle joint: Investigation and treatment options. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111(21):377-388.

- Gudin J. Opioid therapies and cytochrome p450 interactions. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44(6 Suppl):S4-14.

- Harding AD, Flynn Harding MK. Treating pain in patients with a history of substance addiction: Case studies and review. J Emerg Nurs. 2014;40(3):260-2; quiz 292.

- Kampman K, Jarvis M. American society of addiction medicine (ASAM) national practice guideline for the use of medications in the treatment of addiction involving opioid use. J Addict Med. 2015;9(5):358-367.

- Majeed MH, Sudak DM. Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic pain-one therapeutic approach for the opioid epidemic. J Psychiatr Pract. 2017;23(6):409-414.

- McHugh RK, Hearon BA, Otto MW. Cognitive behavioral therapy for substance use disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33(3):511-525.

- Oliver J, Coggins C, Compton P, et al. American society for pain management nursing position statement: Pain management in patients with substance use disorders. J Addict Nurs. 2012;23(3):210-222.

- Opioid Prescribing. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/opioids/index.html. Published 2018. Accessed July 26, 2018.

- Peek J, Smeeing DPJ, Hietbrink F, Houwert RM, Marsman M, de Jong MB. Comparison of analgesic interventions for traumatic rib fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018.

- Polomano RC, Fillman M, Giordano NA, Vallerand AH, Nicely KL, Jungquist CR. Multimodal analgesia for acute postoperative and trauma-related pain. Am J Nurs. 2017;117(3 Suppl 1):S12-S26.

- Radnovich R, Chapman CR, Gudin JA, Panchal SJ, Webster LR, Pergolizzi JV,Jr. Acute pain: Effective management requires comprehensive assessment. Postgrad Med. 2014;126(4):59-72.

- Rui P, Kang K. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey:2015 Emergency Department Summary Tables. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2015_ed_web_tables.pdf

- Shah A, Hayes CJ, Martin BC. Characteristics of initial prescription episodes and likelihood of long-term opioid use - united states, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(10):265-269.

- Shibuya N, Davis ML, Jupiter DC. Epidemiology of foot and ankle fractures in the united states: An analysis of the national trauma data bank (2007 to 2011). J Foot Ankle Surg. 2014;53(5):606-608.

- Sporer KA. Buprenorphine: A primer for emergency physicians. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43(5):580-584.

- Starrels JL, Becker WC, Weiner MG, Li X, Heo M, Turner BJ. Low use of opioid risk reduction strategies in primary care even for high risk patients with chronic pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(9):958-964.

- Todd KH. A review of current and emerging approaches to pain management in the emergency department. Pain Ther. 2017.

- Whiplash - Diagnosis and treatment. Mayoclinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/whiplash/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20378926. Published 2018. Accessed July 26, 2018.

- Witt CE BE. Comprehensive approach to the management of the patient with multiple rib fractures: A review and introduction of a bundled rib fracture management protocol. 2017.