Pain in a cancer patient is not always cancer.

- New site of metastasis, or new cancer

- Pain related to prior cancer treatments

- Non-cancer pain

For patients with cancer, new pains often raise fear of new sites of cancer. For many patients, pain was a presenting symptom of their cancer. So this fear is a valid fear; and while it is an important component of the evaluation of pain in a cancer patient, it is equally important to completely evaluate new pain complaints for another source because not all pain in a cancer patient is cancer. This assessment should include a thorough evaluation of the cancer and its treatment.

Assessing Cancer

- Location of known disease

- Be aware there could be a new metastasis

- Treatments the patient has had

- Chemotherapy

- Biologic therapies

- Radiation

- Surgeries

Pain can be directly related to cancer, but it can also be related to cancer treatment including surgical interventions, radiation, chemotherapy, hormonal, and targeted therapies including immunotherapy. Each of these types of pain has different trajectories and different management strategies. For example, post-operative pain would be expected to improve over time and require less pain medication as a patient heals from the surgery. However, chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy can be a dose-limiting side effect of treatment and may improve, stabilize or even worsen after chemotherapy has stopped. For some of the newer biological agents, pain can herald life-threatening adverse effects. Each of these scenarios requires that the cancer treatment history is elicited.

Non malignant pain occurs commonly in patients with cancer.

Finally, pain in a patient with cancer can be completely unrelated to the cancer. This is particularly true in older adults who are more likely to have comorbid, chronically painful conditions.

A patient with a history of intermittent flares of pseudogout, for example, will continue to have them, and they may even increase in frequency during the course of cancer treatment. One study demonstrated that 27% of cancer patients being treated for pain, also had pain unrelated to their cancer.

In Mary’s case, we are concerned about the possibility of metastatic bone disease as the cause of her pain. Are there other factors that might also contribute to her pain and functional limitation?

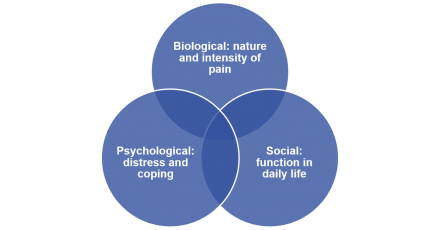

Cancer is a Biopsychosocial Syndrome

Pain is a biopsychosocial syndrome. This means that physical, social and psychological factors all contribute to the overall pain experience. A biopsychosocial treatment approach to chronic pain takes into account the dynamic interplay between physiological, psychological, social and cultural factors.

The biologic and physiological factors, that is, the physical pathology responsible for the pain, are only one part of the equation.

Social factors refer to social functioning in everyday life including who the patient lives with, the activities they participate in, and their ability to independently care for themselves, as well as the resources available to them should that ability be challenged.

Psychological constructs that are associated with distress and that contribute to disability must be evaluated, Examples of these constructs include anxiety and/or depression as well as the patient’s coping strategies both currently and in past difficult circumstances. Psychological distress is common in cancer patients and is screened routinely during oncology visits. Depression also is screened routinely during primary care visits, because it impacts many conditions and adherence to treatment plans.

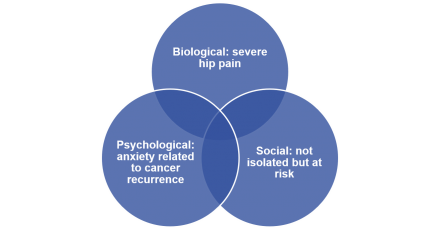

For Mary, we know that the pain in her right hip is severe and, we are concerned about the possibility of metastatic disease.

Mary is not socially isolated because she is an active participant in her senior community. However, she is at risk for isolation because she lives alone.

We also know that Mary is anxious about the possibility of cancer recurrence.

A comprehensive pain management plan addresses each of these aspects of pain.

Differential Diagnosis

Listen to Dr. Childers explain her differential diagnosis for the cause of Mary’s new pain.

X-ray of Femur With Metastatic Cancer

Mary is sent for an x-ray of her leg, which we see here. She has had progression of her cancer in her femur. Mary returns to the office after her x-ray for discussion of the test results with her doctor.

Difficult News

Mary meets with Dr. Childers to discuss the results of her X-ray.

Pain Management

Dr. Childers and Mary discuss the use of opioids to help manage Mary’s pain.

Metastatic Bone Pain

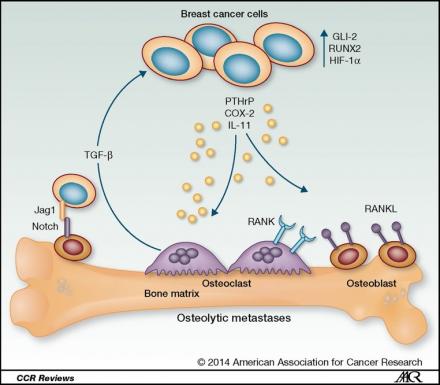

Metastatic bone pain is complex pain.

Bone pain resulting from cancer bone metastasis has complex and incompletely defined pathophysiology with somatic, inflammatory and neuropathic mechanisms. One of the mysteries of this common cause of cancer pain is that not all metastases are painful and pain does not always correlate with the size or location of the lesion.

Significant progress in the understanding of bone pain is being made; and has led to identification of new treatment targets.

Multiple factors contribute simultaneously—but not necessarily uniformly—to the painful sensation.

As tumor cells invade and grow, they cause direct bony destruction, as well as displacement and/or compression of the many nerve fibers present in the bone from the periosteum to the marrow. Tumor cells upset the normal balance of osteoclastic and osteoblastic activity in the bone, to form either osteolytic or osteoblastic lesions. These lesions challenge the strength of the bone, and can lead to fracture.

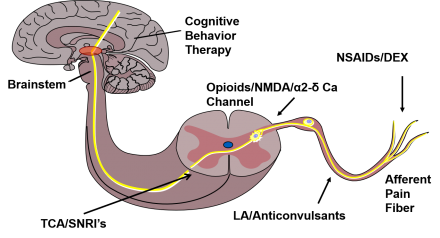

Multimodal Approach

Metastatic bone pain is best managed with a multimodal approach.

- Radiation therapy

- Opioids

- Bone-targeted agents

- Anti-inflammatory agents

- Neuropathic agents

Because multiple factors contribute to metastatic bone pain, a multimodal approach is required for optimal treatment outcomes.

Radiation therapy is the treatment of choice for focal metastatic bone pain. Condensed and even single fraction radiation can offer significant pain relief in as little as one to two weeks. A complete response typically takes longer. Some patients do not achieve adequate relief, and continue to require analgesic medications.

Opioids are a mainstay of cancer pain management. The literature supports use of opioids for moderate to severe cancer-related pain. Bone pain, however, tends to be incompletely responsive to opioids, and escalation of opioids may have diminishing returns. That is, increasing adverse effects may not be associated with meaningful additional improvement in pain. Opioids should always be used judiciously, even in patients with cancer.

Bone- targeted agents including bisphosphonates and denosumab, a monoclonal antibody to RANKL, have demonstrated efficacy in reducing pain scores, delaying pain progression and time to strong opioid use. Bisphosphonates inhibit osteoclast activity and reduce tumor associated osteolysis and pathologic fracture risk. denosumab binds to RANKL which prevents osteoclast formation, thus preventing osteoclast activity.

Corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs both target the inflammatory aspects of metastatic bone pain. Each of these agents has significant potential adverse effects and should be used cautiously and for the shortest duration possible in older adults.

Gabapentinoids, tricyclic antidepressants and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors can be used to target neuropathic pain. However, the evidence of benefit of adding neuropathic agents to opioids for metastatic bone pain remains mixed.

As with any treatment, outcomes should be monitored carefully and ineffective approaches discontinued.

Adverse Effects of Opioids

| Common | Uncommon |

|---|---|

| Constipation | Bad dreams / hallucinations |

| Dry mouth | Dysphoria / delirium |

| Nausea / vomiting | Myoclonus / seizures |

| Sedation | Pruritis / urticaria |

| Sweats | Respiratory depression |

| Urinary retention |

While opioids are generally required at some time to adequately manage cancer-related pain, clinicians must be aware of opioid related adverse effects. More common opioid-related adverse effects include nausea and vomiting, constipation, dry mouth, sedation, and sweating. Constipation is an almost universal adverse effect and when an opioid is initiated a laxative should be simultaneously prescribed. Less common adverse effects are bad dreams which may include hallucinations, delirium, and myoclonus that can progress to seizures, pruritus and urticaria, and urinary retention. Respiratory depression represents a life defining adverse effect and one must use particular caution in persons on higher doses of opioids, have coexistent sleep apnea that is not adequately managed, and prescribed other medications that are sedating such as benzodiazepines or anticholinergics.

Treatment Effects on Pain Pathway

Each of the agents discussed targets different parts of the pain pathway, from the periphery to the brain.

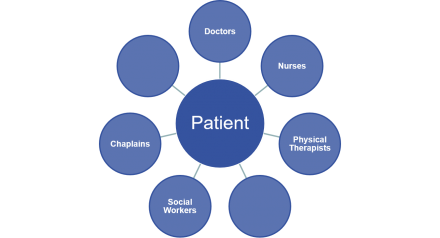

Team Management of Pain

Cancer pain is best managed by a team.

Cancer pain is complex and patients often benefit from interdisciplinary team management, with each member of the team contributing their expertise in a coordinated plan of care. Common contributors to the care team in a cancer patient may vary over time but can include the physician, nurse, social worker, chaplain, psychologist, pharmacist, and therapists such as physical and occupational therapists.

Care Coordination

Care coordination is important.

- Bone Scan

- Staging CT

- Referral to Radiation Oncology

Coordination of care is important so that patients receive a consistent message from each member of their care team, and the care plan remains cohesive with clear goals. Patients can be overwhelmed when receiving bad news, hearing multiple changes to the care plan such as starting new medications, and following up with multiple tests and appointments.

Mary returns for a follow-up visit with her primary care provider 2 months later with new pain symptoms.