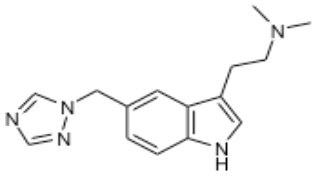

Amitriptyline (Elavil®)

- Tricyclic anti-depressant (TCA)

Amitriptyline (Elavil®)

- Treatment of migraine is an off-label use

- Level of evidence C1

- MOA: inhibits reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine

- AE: sedation, xerostomia

- Contraindicated with or within 14 days of MAOI

- ½ life: 13-36 hr

- Metabolism: CYP2D6 substrate (major)

- Excretion: urine

- Formulations: tablet

- Morgan: 10 mg/po/at bedtime

- prophylaxis

Reference

American Academy of Neurology Quality Standards Subcommittee and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society 2004 practice parameter for the pharmacological treatment of migraine headache in children and adolescents

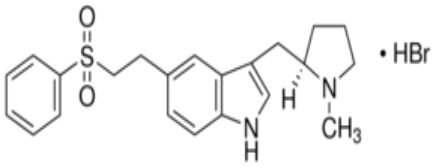

Rizatriptan (Maxalt®)

- Triptan

Rizatriptan (Maxalt®)

- MOA: Selective agonist for serotonin (5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors) in cranial arteries and sensory nerves of the trigeminal system

- AE: chest pain/tightness, flushing

- Contraindications: ICD or other CVD, w/in 24 hr of another triptan, with or within 14 days of MAOI

- ½ life: 2-3 hr

- Metabolism: MAO-A

- Excretion: primarily in the urine

- Formulations: tablet, ODT

- Morgan: as needed as soon as migraine starts

- Acute therapy

Rizatriptan (Maxalt®)

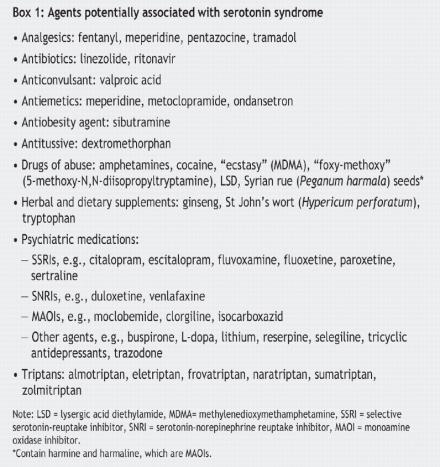

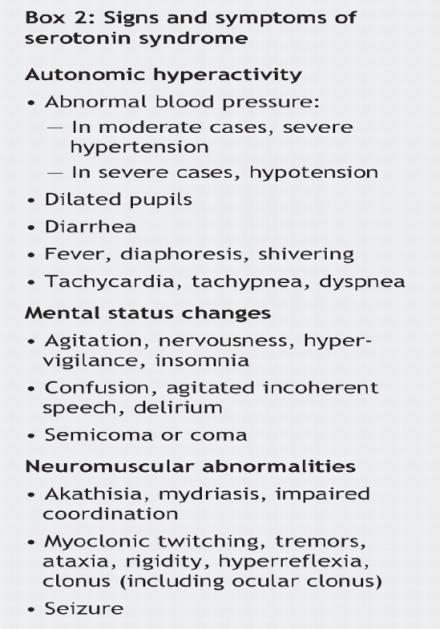

Serotonin Syndrome

Amitriptyline

Major Psychiatric Warnings

- Suicidal thinking/behavior: Antidepressants increase the risk of suicidal thinking and behavior in children, adolescents, and young adults (18 to 24 years of age) with major depressive disorder (MDD) and other psychiatric disorders

- Amitriptyline is not FDA-approved for use in children.

- The possibility of a suicide attempt is inherent in major depression and may persist until remission occurs. Worsening depression and severe abrupt suicidality that are not part of the presenting symptoms may require discontinuation or modification of drug therapy. Use caution in high-risk patients during initiation of therapy.

Summary of Triptans Investigated for Pediatric Migraine

| Generic Name | Brand Name | Dosage Form | Dose | Max. Dose/Day | Clinical Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sumatriptan | Imitrex | Nasal spray | Age: 5-18 years: 5, 10, or 20 mg Weight-based:

|

40 mg | Effective for the acute treatment of migraines in adolescent patients |

| Subcutaneous | Age: 6-18 years: 3-6 mg Weight-based:

|

12 mg | Positive open-label data for those 6 - 18 years | ||

| Oral Tablet | Age: 8-17 years: 25-100 mg | 200 mg | Oral formulation was not statistically significant different compared to placebo | ||

| Zolmitriptan | Zomig | Nasal Spray | Age: 12-17 years: 2.5 or 5 mg | 10 mg | Nasal Spray FDA approved in 12-17 year olds; mixed efficacy results in adolescents; studies suggest nasal spray is more effective than oral formulation |

| ODT | Age: adult: 2.5 mg | ||||

| Oral Tablet | Age: 12 - 17 years: 2.5, 5 or 10 mg | ||||

| Rizatriptan | Maxalt; Maxalt MLT |

Oral Tablet ODT |

Weight-based:

|

30 mga | FDA approved for use in 6-17 year olds |

| Almotriptan | Axert | Oral Tablet | Age: 12-17 years: 6.25-12.5 mg | 25 mg | FDA approved for migraine in 12-17 year old adolescents |

| Eletriptan | Relpax | Tablet | Age: 12-17 years: 40 mg | 80 mg | Studies show reduction in recurrent migraine in 12-17 year old adolescents |

| Sumatriptan/Naproxen | Treximet | Tablet | Age: 12-17 years: sumatriptan 10 mg combined with naproxen 60 mg |

Sumatriptan 85 mg / Naproxen 500 mg | Triptan/NSAID combination approved by FDA in ages 12-17 years |

a = 5 mg daily maximum if on propanolol

Naratriptan (Amerge) and frovatriptan (Frova) have no efficacy studies for the pediatric population

Summary of Medications Used for Pediatric Migraine Prophylaxis

| Drug Name | Medication Class | Dose | Max. Dose/Day | Ages Studied (years) | Adverse Effects and Clinical Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyproheptadine | Antihistamine | 0.2-0.4 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses or 2-8 mg/day | 0.5 mg/kg/day | 16-Jun | Younger patients more tolerant of common side effects (sedation and appetite stimulation); side effects less common if dose is slowly titrated and given at night. |

| Amitriptyline | Antidepressant | 0.25 mg/kg/day or 10-50 mg daily at bedtime | 1 mg/kg/day | Mean age 12 years | Used most often in children; ADE include arrhythmias, weight gain, anticholinergic effects, sedation, and potential overdose; drowsiness can be useful for concomitant insomnia; ECG recommended for dose > 40 mg; worsening of depression or suicidal ideations in children with depression. |

| Propranolol | Antihypertensive | 0.6-1.5 mg/kg/day or 10-40 mg three times daily | 4 mg/kg/day | 16-May | Conflicting results in placebo trials; ADE include bradycardia, hypotension, syncope, dizziness, drowsiness, and wheezing; contraindicated in asthma. |

| Valproic acid | Anticonvulsant | 20-40 mg/kg/day | 1000 mg | 17-May | Considered 2nd line agent; ADE include liver dysfunction (children < 2 years at greatest risk), pancreatitis, somnolence, weight gain, alopecia, menstrual irregularities, tremor, and blood dyscrasia; risk of teratogenicity in females of child-bearing age |

| Topiramate | Anticonvulsant | 1-10 mg/kg/day (usual 2 mg/kg/day or 50 mg twice a day) | 200 mg | 17-Jun | Considered 2nd line agent; FDA approved in ages 12-17 years; not effective in < 12 years; ADE include anorexia, weight reduction, gastroenteritis, paresthesia, somnolence, and cognitive impairment; risk of teratogenicity |

*RCT: Randomized Control Trial; ADE: adverse drug event

Supplements Used for Pediatric Migraine Prophylaxis

| Drug Name | Usual Range | Clinical Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Magnesium | Pediatrics:9 mg/kg/day divided three times daily | May be more helpful in migraine with aura and menstrual migraine; patients tend to have gastrointestinal adverse effects (diarrhea); 1 RCT in 118 children. |

| Adolescent/Adults: 800 mg/day in divided doses |

Conflicting benefit in adults; RCT in 81 adults demonstrated 42% reduction in frequency by weeks 9-12 compared to placebo (16%). | |

| Riboflavin (Vitamin B12) |

200-400 mg once daily | Very limited evidence in children; one trial reported positive results in 41 children with a decrease migraine frequency; NSS compared to placebo in 2 trials of 90 children. Adverse effect include diarrhea and vomiting; orange colored urine reported |

*RCT: Randomized Control Trial; NSS: Not statistically significant

Communicating with Children, Adolescents, and their Caregivers

- Health care providers often have limited experience communicating health information to children.

- Community pharmacists report that they talk with children about their medicine only 20-30% of the time.

- Children require a different approach that considers the developmental level of the child.

- Communication decreases errors and improves adherence

- United States Pharmacopeia has developed a position statement outlining the principles for teaching children and adolescents about medication.

Reference

Benavides S and Nahata MC, editors. Pediatric Pharmacotherapy. Lenexa, Kansas: American College of Clinical Pharmacy; 2013. Chapter 5, Communicating with Children, Adolescents, and Their Caregivers; p.61-66.

Ten Principles for Teaching Children and Adolescents About Medicines

- Children have right to appropriate information.

- Children want to know about their medicine; communicate directly.

- Interest in medicines should be encouraged and they should be taught how to ask questions.

- Children learn by example; actions of parents/caregivers should demonstrate appropriate use of medicines.

- Children, their parents, and HCP should negotiate gradual transfer of responsibility for medicine in ways that respect parental responsibilities and health status and capabilities of the child

- Education regarding medicine should take into account what children want to know about medicine, as well what HCP think they should know.

- Children should receive basic information about medicines and their proper use.

- Education should include information about the general use and misuse of medicines.

- Children have a right to information that will enable them to avoid poisoning through the misuse of medicines.

- Children asked to participate in clinical trials have a right to receive appropriate information to promote their understanding of assent and participation

*HCP = Health Care Provider

Reference

Bush PJ et al. Clinical Therapeutics 1999; 21(7): 1280-1284

Cognitive Development Stages Medication Education

| Approximate Age (years) | Developmental Stage | Description of Stage | Medication Counseling |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-2 | Sensory Motor | Do not see the connection between self and outside objects | Learning about medicine is not possible. |

| 2-7 | Preoperational | Can consider only a single aspect of a situation Can consider only the here and now Have no concept of cause and effect Do not understand the connection between an action and their health Can use symbols or pictures to represent objects |

Hands-on activities are the most effective It is important to include the taste of medicine in your education to them. Example: "This medicine will keep you from getting sick. You will take it when you go to sleep at night. Your mom or dad will help you take the medicine." |

| 7-11 | Concrete Operations | Can focus on many aspects of a situation Can think about concrete events but have difficulty with hypothetical situations Can distinguish between self and effects of the outside world Can understand that diseases are preventable |

Give them time to ask questions, and explain concepts to them. Include a discussion about the adverse effects of medicines that should be reported to parents. Example: "This medicine will help with your headaches. You will take the medicine before you go to bed. It can make you sleepy and give you dry mouth. Work with your mom and dad to make sure you take the medicine right and remember to take it." |

| ≥ 12 years | Formal Operations | Capable of hypothetical thought and logical reasoning Understand how illness occurs and is affect by their actions Begin to understand they can have control of their health |

Typically able to receive a message at the same level as an adult, but keep in mind they may be more embarrassed by certain topics. Example: "This medicine works to help you experience less migraines. This medication works if you use it everyday. It is important to keep using this medicine even when you start feeling better. Work with your mom and dad to help make sure you take this medication everyday." |

Reference

Benavides S and Nahata MC, editors. Pediatric Pharmacotherapy. Lenexa, Kansas: American College of Clinical Pharmacy; 2013. Chapter 5, Communicating with Children, Adolescents, and Their Caregivers; p.61-66.

What do children want to know about their medication?

- How does the medicine taste?

- When do I take the medicine?

- How will it make me feel better?

- How long will I take it?

- What are the side effects?

- Why am I taking the medicine?

Reference

Benavides S and Nahata MC, editors. Pediatric Pharmacotherapy. Lenexa, Kansas: American College of Clinical Pharmacy; 2013. Chapter 5, Communicating with Children, Adolescents, and Their Caregivers; p.61-66.

General tips for communicating with children and adolescents

- Sit at or below their eye level

- Begin by discussing something of interest to the child or adolescent

- Remain calm and nonjudgmental

- Be aware of their body language and respond if needed

- Speak in a normal tone of voice

- Allow the patient to express concerns and ask questions

- Give ample time to respond to questions

- Give your full attention

- Listen attentively and repeat to ensure you understand

- Allow the patient to participate in decision making about their medication

Reference

Benavides S and Nahata MC, editors. Pediatric Pharmacotherapy. Lenexa, Kansas: American College of Clinical Pharmacy; 2013. Chapter 5, Communicating with Children, Adolescents, and Their Caregivers; p.61-66.